Mary Magdalene is often depicted weeping. Byzantine tapestries, medieval carvings, and Renaissance illustrations detail her suppliant tears flowing towards Christ’s feet, the same feet she will bathe and then dry with her unspooled hair. Whether she is sitting alone with her vessel of ointment or performing her damp labour under a table while Christ converses with other holy men, she is always repentant for her fleshy sins.

It’s no great mystery why the motif of weeping, historically deemed an emphatically female state, was so zealously twinned with that of bathing – an archetypal act of subservience and care. More perplexing is why Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and Mary of the Desert were amalgamated into one woman by Pope Gregory in 591 CE in an Easter sermon, which also led to the Magdalene being considered a prostitute, an entirely unsubstantiated claim. More perplexing, still, is how this resultant figure became a moniker for the brutal incarceration of similarly ‘fallen’ Irish girls and women via the church-run, for-profit Magdalene Laundries, which operated across Ireland between 1922 and 1996.

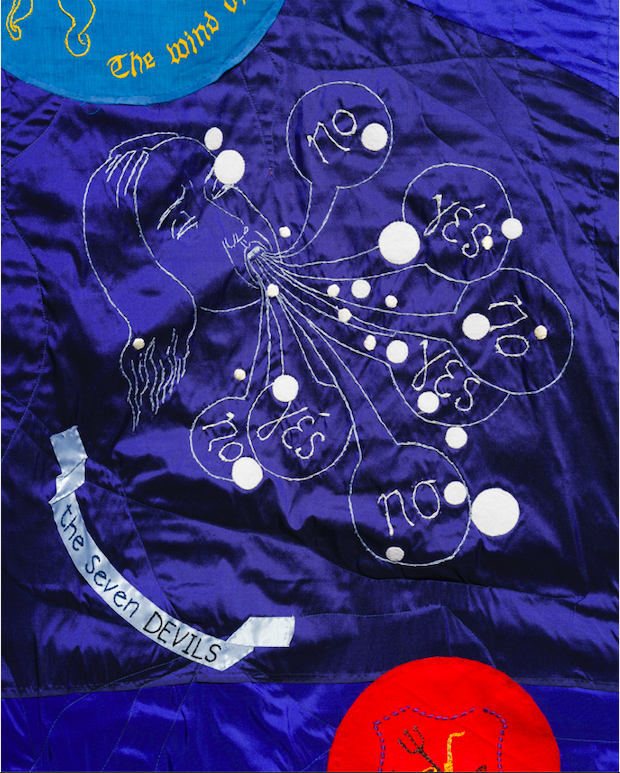

It’s this fraught chain of archaic misogyny, papal projection, and institutional abuse that Rachel Fallon and Alice Maher’s The Map seeks to revisit. The latest instalment in the Magdalene Series – a sequence of commissioned responses to Mary Magdalene’s legacy, curated by Maolíosa Boyle at Rua Red – The Map is twenty-one-feet wide and fifteen-feet high, dramatically lit, and suspended in the centre of the otherwise dark Gallery 1. A monumental textile work comprised of embroidery, appliqué, and crochet as well as painted, printed, and found material, it is a map of a world we have not yet seen. Across a backdrop of deep blue fabric representing the cosmos, we see what appears to be an unfurled scroll depicting islands and larger stretches of land that might be continents. On the left, we see the embroidered Oiléan Olc (Slag Island), a fictional location that playfully includes the Fields of Salomé and Jezebel Heights. In the lower left-hand corner, a female face sparely depicted in white thread blows three ‘Yeses’ and four ‘Nos’ from her mouth; seven speech bubbles that call to the Seven Devils that purportedly possessed Mary Magdalene. Other details include the Mergig (a sheela na gig, mermaid hybrid) and a rosily rendered vulva sporting a hat, sword, and sandals making its way to the Land of the Law.

It is a world we have not seen because it is a world in which Mary Magdalene’s malignant legacy never took hold. Certain iconographies have been rendered null and void: there are no ‘Fallen Magdalenes’ to be pitted against ‘Pure Virgins’. Instead, the Little Laundress is a constellation in the shape of a young girl and the Wind of Change blows with ready force. It is a world where the carnal and the maternal couple together in untroubled unison; the City of Lovers and Big Mammy Land, the She-Wolf replete with teats and phallus, and Greek mythology’s bereaved Niobe shedding tears over her lost children.

Mapmaking, and the supposed concrete data it connotes, is an especially ripe form for subversion, and Fallon and Maher take full advantage. Not only has the wet work of weeping, bathing, and laundering been recast with nautical symbolism, but this rational and colonial form is rendered in a domestic, feminine medium. Textile work is, after all, a brand of female literacy that often precedes or supersedes reading and writing, and while it speaks to a history of invisible labour it is also, as women’s studies specialist Patricia Mainardi tells us, a form ‘in which women controlled the education of their daughters’. It is a discipline that conjures ‘questions of feminine sensibility, of originality and tradition, of individuality versus collectivity’,[1] what women achieve when left to their own resilient devices.

Installed in Gallery 2, We Are the Map is a text and sound installation made in response to The Map and its surrounding research. Again, a work installed in a darkened space performs questions of subversion, female lineage, and collectivity, but its scale is much reduced. In the smaller space, viewers can sit on the single long bench positioned across from several speakers discreetly installed on the wall and listen to the audio work as it plays on a loop. Made by writer Sinéad Gleeson and composer Stephen Shannon, We Are the Map is a vocal work consisting of Gleeson’s own voice as well as the voices of thirty-six other women. After the monumentality of The Map, a charged sense of intimacy comes with the distillation of these vast themes into a succession of female voices. The bulk of the piece details a traveller’s progress over twenty-four sections – the numeration is one of multiple nods to Homer’s The Odyssey. The landscape traversed, however, is the world of The Map in Gallery 1, and the vernacular is lush imagery lifted from the global feminine corporeal – but shot through with an unmistakably Irish trauma. The sensuous, earthy ring of ‘pink lozenge wounds’, ‘fallopian furrows’, and ‘crowns of pomegranate twigs’, is tempered by ‘the first girl child they put in a septic tank’ and a reminder that women’s bodies are ‘a place where bombs go off all the time.’

Once this prose narrative comes to a close, varied female voices including Lynn Ruane, Catherine Corless, Vicky Phelan, Ailbhe Smith, Felicia Speaks, Rosaleen McDonagh, Olwyn Fouéré, Marian Keyes, and local women from Tallaght echo the final line: ‘We are the map.’ This refrain would carry little weight, of course, if we had not just seen a map, which is a gesture of kinship that travels backwards and forwards in time by reimagining women like the Magdalene who have been neglectfully overlooked and actively rewritten, and posing a new set of symbols that bolster rather than rebuke women. Women such as Nan Joyce, Marsha P. Johnson, and the X case girl are also mentioned, and represented as medallions on The Map, rendering it a place (both real and imagined) that women occupy.

The refrain also ensures the imaginative work done in Gallery 1 reverberates in embodied, physical terms. Listening to the voices of these thirty-six women disallows escapism; the point of exercising our imaginative faculty is not, we’re reminded, to briefly bask in the reprieve of forgetting how history did in fact unfold, but to glimpse new conditions of existence we can thereafter move towards.

After spending time with these works, I had American poet Marie Howe’s Magdalene very much on my mind, in particular her short poem ‘The Map’. Here, Howe reimagines Mary Magdalene as a contemporary mother helping her daughter with her geography homework. As she watches her daughter’s small hand reach out and trace ‘the Gobi desert, / the Plateau of Tiber’ in the air in front of her, Mary tells us

I did suddenly see,

how her left is my right, and for a moment I understood.

A woman and her daughter, sitting alone and undisturbed. Between them, they figure out something new about the world. Such are the small intimacies, the pockets of release that occur across continents and kitchen tables. They might evaporate as soon we look away, or they that might linger and accrue inside a collective female heart, gathering momentum.

Like The Map and We Are the Map, Howe’s image feels reparative, restorative. And yet, to call it cathartic would be reductive, insinuating as catharsis does a finite result rather than a process, ongoing.

At the bottom of The Map, thick wefts of red wool unspool and touch the floor. You might mistake them for cords of gushing blood if you could not see, more than fifteen feet above you, the back of the Magdalene’s head. Perhaps this gathered wool is the long flowing hair that has historically served as a means to cover up the Magdalene’s naked body; a hirsute motif of concealment and shame, at last shorn and discarded. For a moment, we might feel robbed of her face; we might hunger after the expression of this liberated Magdalene as she looks over a world where her name signifies an interminable sequence of women who decide their bodies’ fate. But if we could see her face, it would mean she is looking backwards rather than forwards; somewhere other than towards the rich and open future.

Notes

[1] Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, eds., Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany (London: Routledge, 2018), 331.

Sue Rainsford is an Irish novelist and arts writer living in Dublin. She is a recipient of the the VAI/DCC Art Writing Award, the Arts Council Literature Bursary Award, the Kate O’Brien Award, and a MacDowell Fellowship. She is the author of two novels, Follow Me to Ground and Redder Days.