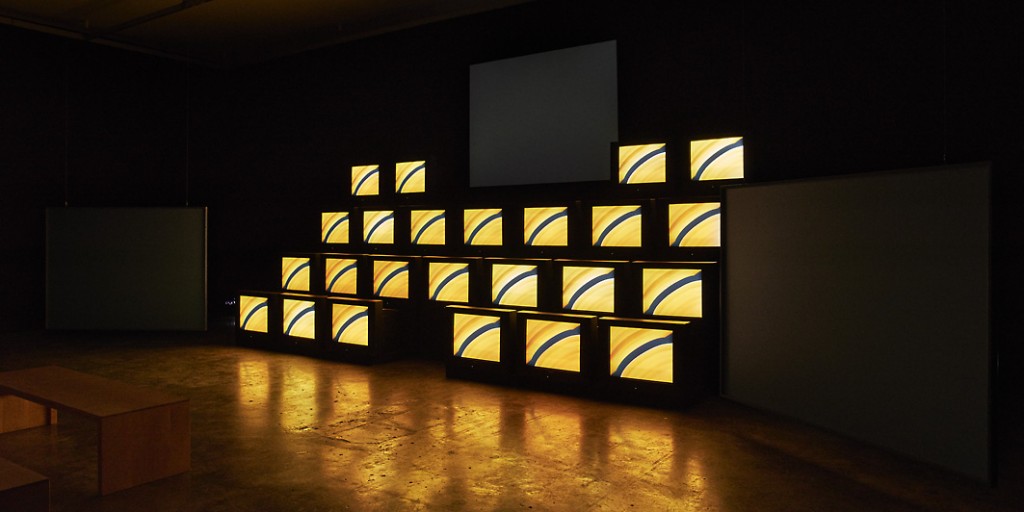

It took me about a minute for my eyes to fully adjust to the twenty-four TV monitors of US artist Gretchen Bender’s Total Recall at Project Arts Centre, and by the time another three larger screens burst into life I got the full wow factor with every moving light, creating the effect of one very large pyramid-shaped display. Today in the space between 3-D cinema and the smartphone screen, Bender’s piece stakes seemingly new ground, which only a gallery can do full justice to. Not that her piece, part of what she termed ‘electronic theatre’, is new – it dates from 1987.

Gretchen Bender

Total Recall, 1987

Courtesy of the Estate of Gretchen Bender

Installation view Project Arts Centre, 2015

Photo: Ros Kavanagh

I recognised a few segments that featured in the piece, including the repetition of one very evocative, slow-motion sequence from Oliver Stone’s 1986 film Salvador, and a short section of the original Channel 4 ident (launched in 1982). The film installation is mostly edited into short repeated sections of material of this nature as well as broadcast news, computer graphics, stock footage, and commercials that soon become very abstracted, poetic, and, when presented in this way, quite beautiful. The up-to-thirty-second corporate idents at the start of movies were, at their inception, cleverly and artfully designed to advertise familiar brands that would remain recognizable for decades. The strength of this branding had the effect of making the installation at Project Arts Centre appear, at first, quite contemporary to me.

The music used in the installation (by the composer Stuart Argabright of The Dominatrix / Ike Yard) alongside these carefully chosen moving images reminded me of the dystopian soundtrack to A Clockwork Orange, and coupled with things like the darkly foreboding ident for Cannon Films, you start to see one of the avenues that Bender is coming from. Contemporary corporate dominance of the media is more total than ever before and Bender’s work is an excellent and far-sighted commentary on this. Since the video was made, corporations have become more adept at catering for, generating, and exploiting consumer taste or product allegiance. Furthermore, corporate image-making and reception has long passed the point where even taking an anti-corporate or anti-government stance can also be profitable, as the American comedian Bill Hicks often alluded to in his stand-up routines during the ’80s and early-’90s and whose own success proves this point. Stone’s Salvador, for example, is often held up as a critique of US foreign policy during the ’80s, and this might be why Bender chose to include fragments from the film in her piece.

I loved the moment when all of the screens were overwhelmingly filled with the choices of upcoming films from some movie-company’s trailer, most of which I had never heard of. It was by reading through a list of these titles that I realised how Bender achieved a kind of ‘appropriation in advance’ of the Hollywood film Total Recall, which was loosely based on a short story by Philip K. Dick about a corporation that sells implanted memories. The Hollywood film was still in development when Bender was making her work. Total Recall, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, was finally released in 1990 before being recycled for a new generation in 2012, this time starring Colin Farrell. This unending variation of the same images and ideas can also be seen as consonant with what Bender is doing here with her piece.

Gretchen Bender

Total Recall, 1987

Courtesy of the Estate of Gretchen Bender

Installation view Project Arts Centre, 2015

Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Bender, who died in 2004, developed a signature style of very fast edits (common currency today), which can be seen in some of her commercial work from this period too, particularly in her collaborations with artist and music-video director Robert Longo. In the video for New Order’s ‘Bizarre Love Triangle’ (1986), one can see where her input is most evident. Her visual language is like a remix or a cutup, full of entertaining surprises and thought-provoking associations for the viewer. During this period of innovation, she also edited the fast-paced opening sequence for the primetime TV show America’s Most Wanted. She was, to some degree, a well-placed TV insider who understood the medium.

In Total Recall she reminds us of the unreality of these images. She shows them as the component parts they are, ready to be utilised and read in any number of ways for ultimately commercial but sometimes more sinister ends.

Very fittingly, to enter into the gallery space one passed through a specially commissioned theatre-type curtain made by the Irish artist Oisín Byrne. The heavy, monochrome material displayed Bender-like images (test cards, TV static, etc.) and marked the boundaries between the outside surface world, the internal exhibition space, and the world of the imagination. The curtain heightened what the show offered, that being a Wizard of Oz–type of behind-the-scenes glance at some features of the mechanics and workings of what is familiar (and spectacular) in contemporary image production.

Stephen Rennicks is an artist and writer based in Co. Sligo.

Note:

Link to Youtube video of New Order’s ‘Bizarre Love Triangle’ here.