And it seems to me the struggle has to be waged

on a number of different levels:

They have computers to cast the I Ching for them

but we have yarrow stalks

and the stars

it is a battle of energies, of force fields, what the

newspapers

call a battle of ideas

to take hold of the magic any way we can

and use it in total faith

to seek help in realms we have been taught to think of

as ‘mythological’

—Diane Di Prima, Revolutionary Letter #45, 1971

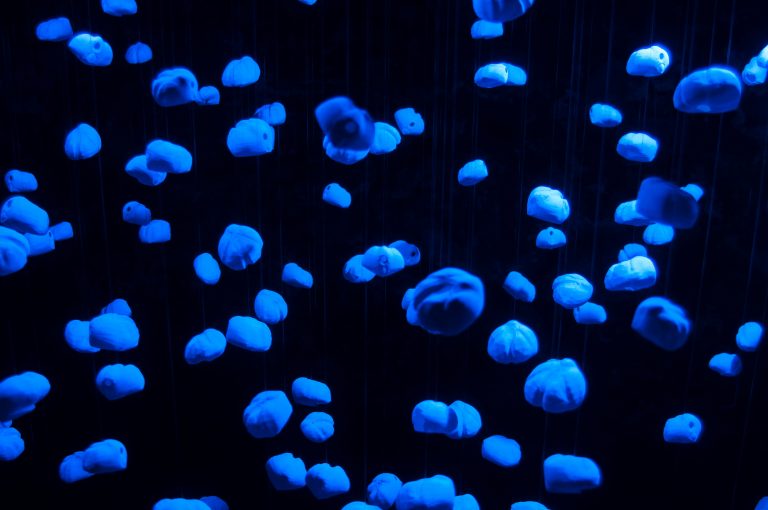

I am looking at all this from what feels like a great distance. From a distance and back through time, I try to summon the memory of how light moved across some specific surface, how sound reverberated in a cavernous space. My brief, for this text, is to respond to what the curators of this year’s Periodical Review at Pallas Projects/Studios have selected as some of the most notable exhibitions or practices or events in Ireland over the past year.1 I am conscious of the fact that I haven’t seen as much as I’d like. The pressures of work, physical difficulties, and sustained demands on my time meant I missed things. Constantly anxious about failing to meet commitments, I often felt I couldn’t move from my desk. So, in the cases where I was not present, I project myself, speculatively, in time and space, trying to connect with what these artworks were like, or what they might have been like. It’s a form of magical thinking, conjuring mental images from bits of text and documentation, from unreliable scraps of memory. Magical thinking, or the belief that one’s thoughts and feelings can affect the outcome of an event, is often understood as a strategy for feeling more control over one’s environment, for coping with the unknown. It’s a defence against anxiety, a way of earthing oneself.

Periodical Review 12, Practical Magic, installation view

Courtesy of Pallas Projects

Photo: Louis Haugh

It has become commonplace to describe our current moment as an age of anxiety: a statement so self-evident as to seem trite. There are times when the multiple crises facing us – the realities of inequality, of environmental degradation, resource use and political instability, of the returned spectre of atomic weapons, of the collapse of traditional structures of power, of the atomisation of communities, and the disappearance of languages – seem so vertiginously profound, complex, and entrenched as to make one breathless. It’s not that we’re experiencing a concatenation of crises so much as a complete collapse of context. Rather than face the realities of a situation so insurmountable, it seems easier to surrender to the hollow core of digital noise, spectacle, and algorithmic control. The foundations of our reality begin to crumble, shrinking the field of the possible, freezing us an in anxious state of paralysis.

Antonio Gramsci’s bleak diagnosis of the 1930s still holds purchase: ‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born.’2 Gramsci was speaking of the emergence of fascism against a background of capitalist crisis and failure of anti-capitalist forces, but his statement feels relevant again at the threshold of what sometimes seems like a second Dark Age, one likewise characterised by widespread denial and self-deception. If the ‘old’ that is dying is the concept of a ‘Western civilisation’ based on rationalist Enlightenment principles, as well as, potentially, the age of capitalism (which as Silvia Federici points out coincides with witch hunts and the end of alterity), then it becomes striking the extent to which artists are moved to look back to an ‘older old’.3 In our fraught, embattled context, other, older forms of knowledge, such as mythology, ritual, and magic suggest ways of imagining, if not a new future, then at least new ways of grounding oneself in the turbulent present.4 As the philosopher Federico Campagna has recently argued, magic is a potential therapy for the pathologies of our existence; pathologies such as the foreclosure of the future and the feeling that we are incapable of fundamentally changing the direction of history.5 A therapeutic injection of magic, Campagna suggests, might be key to overcoming this paralysis.

The coincidence of magic and art practice is not new – it has been subject to repeated ‘resurgences’. The Czech painter František Kupka was a practising medium.6 In her diary, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint recorded that her path-breaking series of abstract works, The Paintings for the Temple (made between 1906 and 1915), were ‘commissioned’ by a spirit called Amaliel, whom she encountered on the astral plane during a séance.7 Wassily Kandinsky attended private fêtes involved with magic, black masses, and pagan rituals. Kazimir Malevich believed in zaum – a Russian term meaning ‘beyond reason’ or ‘beyond the mind’ – a supra-rational process by which connections could be made that transcended the laws and limits of the everyday world.8 These esoteric theories spurred the belief among certain members of the avant-garde that their work had a vital emancipatory role, which was to inspire the revolutionary consciousness of the people and lead them to the promised land of spiritual and socialist utopia.9

In 1974, Lucy R. Lippard wrote about artists such as Ana Mendieta and Mary Beth Edelson who were looking back to a mythical domain of prehistory as a strategy of evading the patriarchal colonisation of the art-historical canon, and in the process finding ‘animist energies of connectivity.’10 More recently, the feminist reception of the occult in contemporary-art practice has meant that the figure of the witch has become a potent motif for queer feminist, environmentalist, and postcolonial reinterpretations, from Marina Abramovic’s Spirit Cooking performance (1996) to Jesse Jones’s Tremble Tremble (2017) and Tai Shani’s Neon Hieroglyph (2021).

Cecilia Bullo, Suspirium: archeological delusion I, 2022

Earthenware, latex, cement, aloe vera extract, gold leaf, hardware, 75 × 55 × 35 cm

Courtesy of Pallas Projects

Photo: Louis Haugh

As Georges Bataille has observed, there are parallels between the figure of the artist and the sorcerer’s apprentice, as the practitioner of magic ‘does not encounter demands that are any different from those he would encounter on the difficult road of art.’11 However, I think it’s more useful to draw those parallels slightly differently and to consider those things we call magic, or shamanic, or ritual practices as other forms of knowledge, ways of knowing and modes of thought that are irreducible to Western rationalism. To borrow Tom Holert’s words, such practices can be understood as presenting ‘a repertoire of cognition that is based in bodily sensations, in affect, in empathy.’12 Holert was writing about art practice as a form of knowledge production, but approaching esoteric or arcane rituals as a kind of ‘counter knowledge’ is compelling. This is particularly true when these practices are understood as broadly incorporating feminist, queer, and decolonial epistemologies and systems of thought that pursue an excavation of what Michel Foucault termed ‘subjugated knowledges’ (whether historical or present day).13 In so doing, we can position these esoteric procedures as a potential skeleton key for releasing the deadlocks formed by the repressed religious, teleological, and colonial foundations of modernity.14

On looking through the work selected for Periodical Review 12, I’m struck by the array of artists engaging with mythology, ritual practices, and the use of powerful totemic objects in their work. Cecilia Bullo’s spare but visceral sculptural apparatuses combine plant forms, archaeological references, and protective amulets to tap into a matrilineal prehistory as well as a more intimate family history. Her work mixes references to archaeological fragments – Gorgons, Sheela-na-gigs – with medical implements and casts of plants and animals. OFFICINALIS I is a series of portraits of a spiky, spidery aloe vera plant, taken from a cutting in her mother’s garden in Italy, which had in turn been planted by her grandmother. Bullo describes the plant as a migrant, landless fossil, one that connects her with family and a living archive of embodied knowledge and healing.

Thaís Muniz’s sculptural textiles, performances, and protection rituals think through the capacities of the headwrap or turban as a potent, wordless object of connection for Afro-diasporic communities. For Muniz’s Ori Blessings: A Contact Performance, performed in Glór in Ennis, the artist offered to adorn attendees’ heads with sculptural wraps as a way of introducing an audience to non-European aesthetics and knowledge, here the Yoruba concept of Ori referring to spiritual intuition and destiny. In both cases, symbolic and ritual objects offer both a salve and a potent retort to misogynistic violence and the continued trauma of immigration, displacement, and racism.

Thaís Muniz, Darling, Don’t Turn Your Back on Me, 2021

Courtesy of Pallas Project

Photo: Cristiane Schmidt

The ways in which time and territory are conventionally calculated were countered in two notable projects that offered critiques of reductive modes of measurement Metabolic Time / Am meitbileach, a group show at Project Arts Centre, invited artists and researchers to give insights into ways of measuring time that have been abandoned in our culture of instantaneity and speed. Methods of keeping or registering the passage of time that are haptic, ancestral, or corporeal offer an alternative to the colonialist and capitalist tool that is ‘clock time’. Meanwhile Léann Herlihy’s Cartography of the Middle of Nowhere, a project that unfolded through a publication and mobile billboard, proposed a speculative approach to mapping, guided by biography, mythology, and queer desire, gesturing to the nuances of place glossed over by conventional map making. Other artists explored ways of connecting with land and history by referencing the occult and pagan practices in a more tongue-in-cheek manner.

The Ecliptic Newsletter’s output of zines and cassettes presents a fantastically sardonic mash-up of dolmens, low-cost supermarkets, abandoned gyms, and tech hubs as a way of posing questions about access to ancient sites and monuments in a rapaciously capitalist economy. Similarly Ruth Clinton and Niamh Moriarty’s radio play Go West relates the story of a ghostly encounter on a train between a tarot-card-reading bureaucrat and an American artist as a satire on the state’s management of our cultural heritage and infrastructure. In a very different vein, Gillian Lawler’s portrait of her mother, Mary Lawler (2021), painted after her death, realises the subject in pale shades of grey, green, and pink. Lawler has described her paintings as portals, where forms can pass through, relating this to Celtic ‘thin places’ where people and spirits can move freely between states of being. In these instances, magical thinking offers a way of travelling across worlds and through time, to connect with ancient landscapes and with people now dead.

Léanne Herlihy, Beyond Survival Expert, 2022

120 mm film

Courtesy of the artist and Pallas Projects

Photo: Niamh Barry. Assistant: Aoife McGrath

If we consider the artist’s oeuvre as a body of knowledge produced over time, then the act of looking back over one’s production becomes not solipsistic but yet another form of magical thinking; a way of generating new meaning from a practice. Kevin Atherton’s personal time-travel experiment, a kind of Beckettian Back to the Future, confronts his younger self in artworks made decades before. In Boxing Re-Match (1972–2015), a work included in Kevin Atherton: The Return at the Butler Gallery, Kilkenny, Atherton literally spars with the apparition of his younger self in a knowing send up of masculinity and artistic ambition.

Tom de Paor’s retrospective at VISUAL Carlow took the idea of looking back to a cosmological plane: i see Earth took its title from cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s radio communications during the first successful orbit of the planet. Gagarin was the first person to experience what psychologists call ‘the overview effect’, a profound mental shift that comes from observing Earth as a fragile object in the vastness of space. i see Earth articulated this epiphanic shift of perspective by choreographing an immersive, multi-sensory experience, with de Paor’s architectural drawings literalised in space as monumental suspended sculptures in whip thin cobalt blue steel. The viewer entered the building by passing under a steel vessel etched with the name Arethusa, a naiad from Greek myth who was transformed into a spring that flows into the sea. Linking the formally diverse exhibition was a concern with environmental fragility, the fundamental interconnection of people and materials, and the possibilities and limits of communication. It’s a concern shared by Christopher Steenson, whose sound installation in the adjoining gallery, Soft Rains Will Come, channelled through portable transistor radios, functioned as a kind of oracle, broadcasting predictions from a future landscape transformed by climate change.

In a recent feature in ArtReview, ‘The Return of Magic in Art’, J. J. Charlesworth argues that ‘while much of the new magical thinking returns to the old countercultural aspiration to “expanded consciousness”, and a psychedelic oneness with the world, it’s really a “regression of consciousness”, a rejection of facing reality as it is, a retreat from trying to make sense of it and acting to change it. Magical thinking is a projection of wish-fulfilment onto a reality we’d rather withdraw from, into one where the troubles and contradictions of the modern world are resolved by merging the imaginary and the real.’ 15 I would argue that magical thinking as it manifests in contemporary practice is emphatically not escapist but motivated by a sincere desire to engage with, to oppose, and to bolster oneself against the multiform crises of the present. This is not an act of wish fulfilment or self-deception but an assertion of forms of knowledge that have been historically discounted or suppressed. Audre Lorde famously argued that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’; that conventional theories and methodologies can never disrupt the intersectional oppressions that buttress our current state of inequity.16 Magic in this context is not a diversion, but a powerful strategy of practical resistance.

Notes

1 The selectors of Periodical Review 12 are Siobhán Mooney and Julia Moustacchi (Basic Space) and Mark Cullen and Gavin Murphy (Pallas Projects).

2 Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks(1930; repr. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1971), 276.

3 Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2009), 11.

4 The age of reason, as Kwame Anthony Appiah has noted, is also a delicate euphemism for ‘white’. See Kwame Anthony Appiah, ‘There Is No Such Thing as Western Civilisation’, Guardian, 9 November 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/09/westerncivilisation-appiah-reith-lecture.

5 Federico Campagna, Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 5–6.

6 Michael Brenson, ‘How the Spiritual Infused the Abstract’, New York Times, 21 December 1986, section 2, page 1, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/21/arts/art-view-how-thespiritual-infused-the-abstract.html.

7 Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘Hilma af Klint: The Invisible, the Spiritual, the Occult’, Purple Magazine, 2019, https://purple.fr/magazine/the-cosmos-issue-32/hilma-af-klint-the-invisible-thespiritual-the-occult/.

8 Brenson, ‘How the Spiritual Infused the Abstract’, 1.

9 Donald B. Kuspit, ‘Utopian Protest in Early Abstract Art’, Art Journal 29, no. 4 (1970): 430.

10 Jamie Sutcliffe, ‘Magic: A Gramayre for Artists’, in Magic, Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. Jamie Sutcliffe (London: Whitechapel; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), 19.

11 Georges Bataille, ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’, in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927– 1939, trans. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 223.

12 Tom Holert, Knowledge Beside Itself: Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2020), 61.

13 Holert, 61.

14 Christoph Chwatal, ‘Book Review: Tom Holert, Knowledge Beside Itself: Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics’, Third Text, 12 October 2020, http://thirdtext.org/chwatal-holert.

15 J. J. Charlesworth, ‘The Return of Magic in Art’, ArtReview, May 2022, https://artreview.com/the-return-of-magic-in-art/.

16 Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 110–14.

Sarah Kelleher is an independent arts writer and curator based in Cork.

This essay was originally published for Practical Magic: Periodical Review 12, 10 December 2022–28 January 2023, and was commissioned by Pallas Projects and PVA, as part of the ‘PPS/PVA Visual Art Writing Commission’.