Cliona Harmey

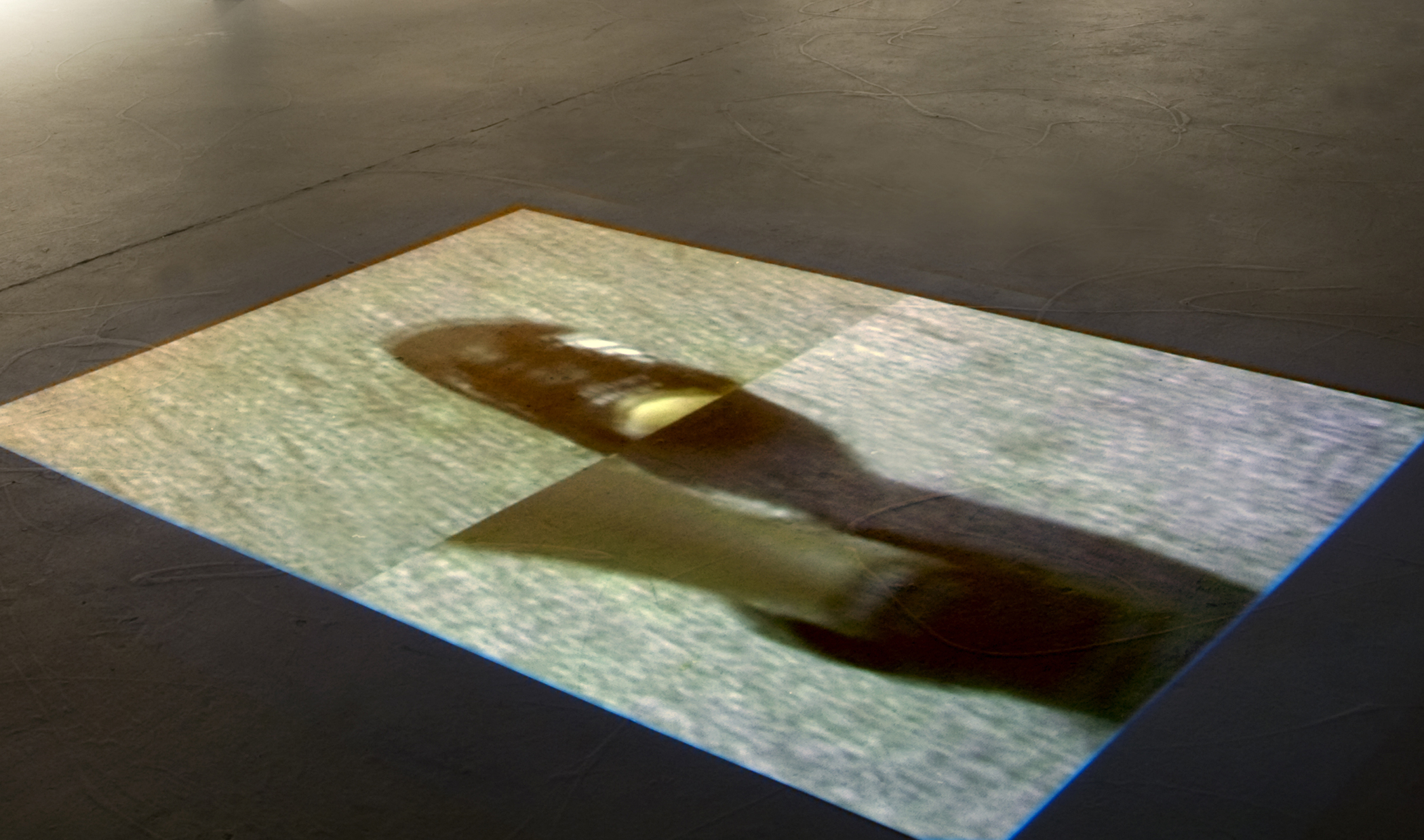

Installation documentation of Dublin Ships, 2015

Photo: Zak Milovsky

Courtesy of the artist

The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They

weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are

indistinguishable from it.

– Mark Weiser, The Computer for the 21st Century, 1991 [1]

In his essay, Mark Weiser proposes writing as an example of a technology that is so much a part of our environment, so ubiquitous, that we no longer perceive it as such. Cliona Harmey’s Dublin Ships employs a number of everyday technologies, including writing, to create interventions into a variety of public spaces. The premise of her project is deceptively straightforward. The names of the two ships, which have most recently entered and departed Dublin Port, are combined and broadcast in three ways simultaneously: as an automatically generated tweet from a dedicated Twitter account;[2] as an automatically updated list on the project website’s log page; and in real space, via a pair of large LED screens sited at Scherzer Bridge on the north bank of the River Liffey.[3]

Dublin Ships unfolds according to a set of rules. A programme running on a computer accesses information from a website dedicated to marine traffic and from a pair of receiving antennae stationed in Dublin Bay.[4] Each time a boat passes into or out of the port, a tweet containing the newly generated name combination is sent, and the log page and outdoor screens are updated.[5]

At a basic level, the project could be understood as an algorithm that is intended to produce and make public what the website describes as ‘a kind of poetic writing’. Perhaps the tweets that @dubships itself has favourited give an indication of what exactly Harmey means by this? Recent examples include:

LEMONIA | CELTIC MIST

STOLT RAZORBILL | ULYSSES

HOEGH JEDDAH | AURORA

SOUTHERN HIGHWAY | SEATRUCK POWER

GAS CERBERUS | BRO DELIVERER

Each of these word combinations evoke something of the surreal flavour and scattershot imagery of race-horse names, but if you say them out loud, they also function as pure rhythm and sound in the manner of concrete poetry.

Interestingly, Harmey’s ship name combination strategy is closer to an old-school (analogue) Burrough’s cut-up, than the computationally enabled (digital) linguistic strategies employed by a similarly Twitter-enabled project like Low Animal Spirits.[6] Dublin Ships acts as a kind of critical infrastructure, with a focus on circulation and flow, rather than on the act of ‘processing’, which is often a characteristic of technologically enabled work. Its only act of ‘creation’ in the traditional sense, is to put one ship name beside another and place them in public.

Cliona Harmey

Dublin Ships, 2015

Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Courtesy of the artist

This no-frills approach, which is consistent throughout the project, is most pronounced in the appearance of the monochrome screens. Both are sized to fit perfectly into the steel frameworks atop the Scherzer Bridge that spans North Wall Quay. To quote a friend, ‘They look like they grew there.'[7] Given the austerity of the displays’ all caps, san-serif black-text-on-white/white-text-on-black design, their proximity to The Samuel Beckett Bridge is apt. Their apparent simplicity recalls the playwright’s desire to pare things back to their essentials. Although their scale and placement call to mind the kinds of LED displays usually used at large public events or for the purposes of advertising, the stripped down aesthetic of both the screens themselves and their content, communicates a different intention. They read as carriers of information. This is even more pronounced at nighttime when the pulsating LED ribs that decorate the National Convention Centre’s tilted cylindrical facade act as a multi-coloured backdrop.

One of the tricky aspects of public art is that it is often the case that most of the audience have not willingly subscribed to the experience. As a temporary public artwork that was commissioned by Dublin City Council’s Public Art Programme through an open call for proposals, Dublin Ships needs to simultaneously address multiple audiences with differing amounts of contextual knowledge. The success of a public art project is often judged by the degree to which it manages to carry off this juggling act.

Harmey’s project has smoothed its transition into the public’s consciousness through various mediation strategies. In parallel to the website and the Twitter feed, information about the work has been disseminated in other ways: through a launch event at which the CEO of Dublin Port made a speech demonstrating an encouraging openness and a nuanced understanding of art and its potentialities; through articles and features in the media, both national and niche; and through the ongoing hyperventilation of social media.[8] In addition, Q-Codes printed on stickers have been affixed to the Scherzer Bridge at head height, so that curious passers-by can inform themselves of the background details via their smartphones. All of this has contributed to the feeling of public goodwill it has generated.

Cliona Harmey

Dublin Ships, 2015

Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Courtesy of the artist

The website claims that ‘the work also attempts to interrupt the speed of instantaneous data and return it to the speed of movement of real entities in space’.[9] My temporal experience of Dublin Ships has been much more complex than this. I have experienced it as a fleeting glance to the right while driving north over the Beckett Bridge, or as a long take en route up the North Quays on foot. Each time, I have found myself imagining the experience from the perspective of the residents and commuters who pass along these routes at the same time every day. I found myself wondering about the degree to which the screens become part of the background of their experience. Or does the shifting text mean they’re always aware of their presence? The work experienced via Twitter produces a different sensation, where the rhythm of textual turnover and hence, the movement of maritime traffic, is more apparent. Sunday nights always seem to be busy. There are bursts of activity followed by long lulls. I could easily list the names of ten or twenty ships that regularly pass through Dublin Port off the top of my head. I have learned things.

In recent years, the term post-Internet art has been employed to describe artworks that deal with the ways in which certain technologies, and the Internet in particular, have altered modes of aesthetic production and interaction. Many would argue that, as terms go, its so vague as to be useless, but it persists nonetheless and is often employed as a shorthand to refer to a particular aesthetic. In my opinion, the significant activity, in terms of techno-cultural shifts, is taking place at an infrastructural level. Claims are often made for post-Internet art in relation to its engagement with these architectures of technology and it is undoubtedly significant that artists are interested in engaging with this subject matter. In my experience, however, it is rare for projects to actually make good on these claims. It is often the case that the surface effects of these systems, rather than the systems themselves, are what is of concern. Exceptions include the ouevre of Hito Steyerl and works by Aleksandra Domanovic, Yuri Pattison, and Simon Denny, among others. [10]

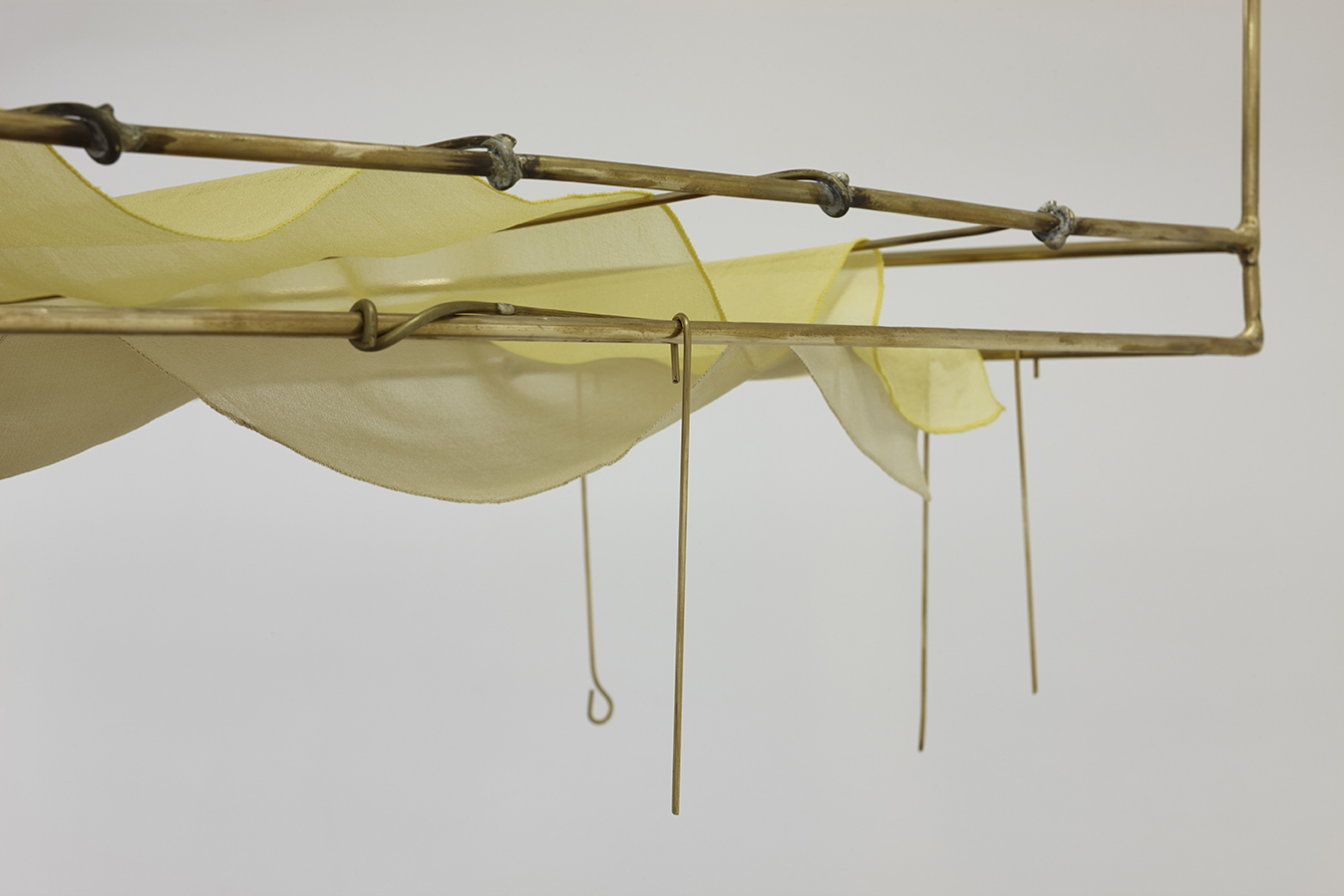

This kind of structural and infrastructural interrogation has been present in Harmey’s work for some time now, but in an almost Zen-like way.[11] Last year’s ‘Troposphere’ show at PP/S comprised four sculptures, a collection of desaturated and precisely tumbledown assemblages, two of which incorporated live data and/or video feeds.[12] The show was accompanied by a number of events, including a public conversation with Dr. Francis Halsall, in which Harmey talked about her fascination with the politics of hacking, including IKEA-hacking.[13] A little later on, she stood up and while continuing to address the audience, partially dismantled one of her sculptures in a single deft movement, gently cradling a hybrid analogue/digital-imaging assembly in her hand for a while before slipping it back into place. Her familiarity with her materials, coupled with the urge to demystify and repurpose everyday objects and systems, is at the heart of Dublin Ships, albeit with some shifts in scale and a tip in the balance between the real and the virtual. There is a confidence in the work’s reduced vocabulary and its mature handling of the relationship between form and content in a techno-cultural context, which points to an extended engagement with both the materials and the subject matter.

Cliona Harmey

Install shot from ‘Troposphere,’ 2014

Photo: Emma Haugh

Courtesy of the artist

Dublin Ships deals with visibility, specifically the act of making things visible, but crucially, it is not about images. Of course, images of the artist, the screens and the almost touristic flavour of their setting, have been widely circulated, but these are, in a sense, red herrings. The work has more to do with the routes and routines of joggers and commuters, and ferrys and oil tankers, than the refresh rate of a screen. The text collages act as a linguistic interface between transportation systems, ferrying their cargo to and fro across ancient seas, and the minds of the consumers whose desires they exist to serve. Dublin Ships inhabits the spaces and relationships between language and ‘things’. It takes place in the imaginations of its viewers/readers as they digest yet another pair of names and mentally jump-cut to the diesel-fuelled hulks churning through Dublin Bay. It addresses the mysterious spaces called up from their subconscious through an encounter with a simple juxtaposition of names.

Dennis McNulty is an artist based in Dublin.

Thanks to Rachel O’Dwyer for bringing Mark Weiser’s essays to my attention.

NOTES:

[1] https://www.ics.uci.edu/~corps/phaseii/Weiser-Computer21stCentury-SciAm.pdf

[2] https://twitter.com/dubships

[3] http://www.dublinships.ie/log

[4] http://www.marinetraffic.com/

[5] Judging by the reaction on Twitter, the most popular recent combination was MAYBE | MAYBE which was retweeted and favourited six times. Seems like Dublin Ships followers are comfortable with uncertainty.

[6] https://twitter.com/lowanimalspirit Low Animal Spirits is a collaboration between Ami Clarke and Richard Cochrane described as a ‘live model of HFT (high frequency trading) dealing in words sourced from global news for virtual profit whilst speculating on their usage – tweeting speculative headlines’. The work takes the form an installation and an ongoing Twitter feed. For more information on the Cut-Up technique see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cut-up_technique.

[7] http://www.dublinships.ie/#the-sherzer-bridges The Scherzer Bridges are located in what is now Dublin’s Docklands, an area of the city that has been subject to the kinds of transformations, both legal and physical, that have shaped dockland areas the world over in the wake of the containerisation of shipping. They are typical of the infrastructural remnants that are often left in place as a physical reminder of an area’s historic function.

[8] List of links to articles.

http://www.tradewindsnews.com/quarterly/

http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/the-shipping-news-dublin-is-reacquainted-with-its-docks-1.2098126

http://afloat.ie/port-news/dublin-port/item/27854-%E2%80%98dublin-ships%E2%80%99-public-artwork-led-display-along-the-quays

http://www.businessandleadership.com/marketing/item/49472-new-public-art-installation

http://dublinportblog.com/2015/01/dublin-ships/

http://www.dublinpeople.com/article.php?id=4561

[9] http://www.dublinships.ie/site/#introduction

[10] I acknowledge that this is an oversimplification of an incredibly complex set of relationships and that my position necessitates further clarification, which I will attempt to provide in an article at some point in the future.

[11] In 2002, Harmey and I collaborated on a temporary, process-based, Internet project called Seapoint. The work drew on the poetic qualities of the Beaufort Scale for quantifying wind speed.

http://www.clionaharmey.info/media/spointoffline.htm

[12] http://pallasprojects.org/index.php/project/cliona-harmeytroposphere

[13] http://www.ikeahackers.net/

note: dates of title changed at 14:16 on 28/07/2015