Michael Waldron: Your work has increasingly embraced a very particular rural vocabulary, one that is riven with complexity and appears to be informed by your native Dingle Peninsula. Can you talk about your relationship with this landscape?

Laura Fitzgerald: The rural has always made me very happy and has also driven me a bit mad. I long to escape to it but then when I get there, I find myself grated off the reality of it. First, the rural can be a right fucker to deal with. It is badly behaved, unpredictable, contradictory, and often soggy. Second, the rural is not nature. This was first brought to my attention during my BA in NCAD nearly fifteen years ago by the artist Fergus Feehily. Growing up in the countryside, I had automatically assumed that the green fields of home and the desire associated with them were nature itself. Therefore this longing for the rural could be sated by sitting in a field or by getting closer to or living within the rural landscape. Now I realise that these places are deeply artificial – nearly as toxic (as we now know) as eating a box of smarties, especially the blue ones. I find it interesting (and worrying) that nowadays my innate instinct to glance sideways full of desire at a piece of this patchwork is quickly followed by a deep sense of dread. The fertiliser green that colours much of rural Ireland, the velvety sheen like a vintage jacket, belies the bags of nitrogen pumped into it underneath. Floating, bloated fish come to mind, lying on their sides on the surfaces of rivers. Acid rain falls harder than recorded in any geography book I ever read.

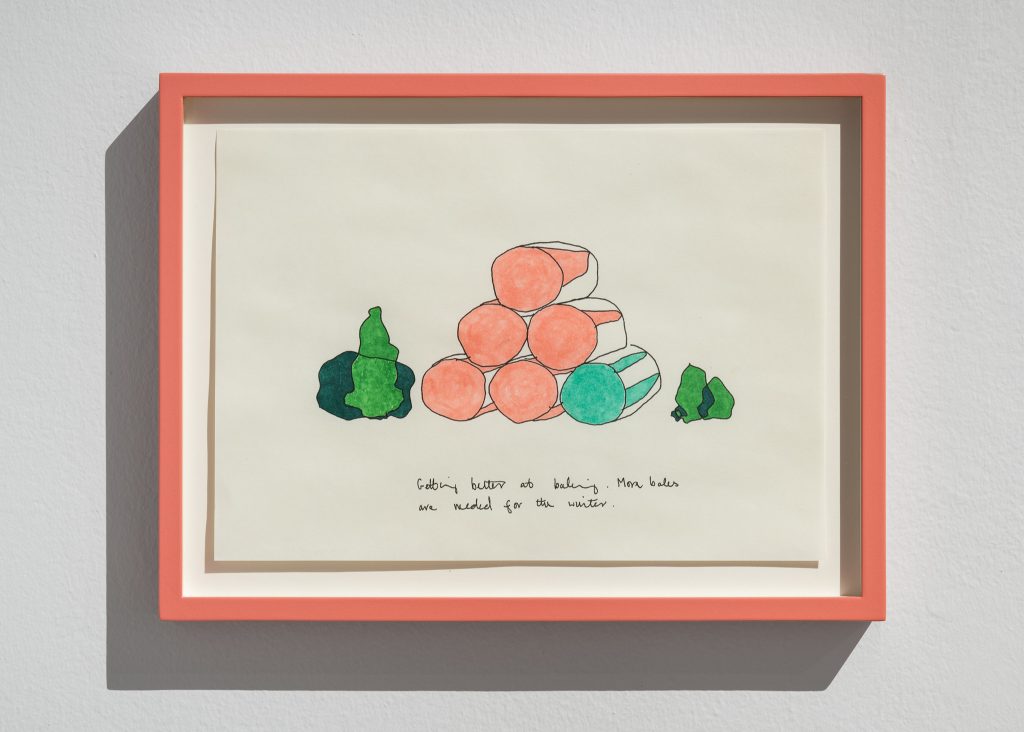

Installation view of Laura Fitzgerald, I have made a place, 2021

Courtesy of the artist and Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

MW: Considering this complexity and artifice, your work can appear simplistic in form. As objects, your works reference rocks, ditches, heritage structures (oratories and beehive huts), hay sheds, bales, and more besides. Your drawings and videos also respond to, or are set in, this landscape but are not always about it. Rather they seemingly offer entry points into what’s really on your mind or act as metaphors for aspects of the art world. How does the rural function in your work?

LF: The beehive huts along Slea Head Drive charge €3 for entry; the ditches are muddy and wet, and I get stung by nettles. The silage bales are off limits; no one is allowed climb on them. The art world, or the illusion of the art world, is also a bit like this I find – the massive studio with a huge heating bill, the superstar LA artist on antidepressants with a serious cocaine habit, the huge art college bill that slowly drip feeds in the hopes of freedom at a later point in life. None of these narratives are totalities or truths but tiny vignettes – my own small stories I tell myself. I find there’s a very similar gap, in both the art world and the countryside, between appearance and reality.

Recently I sent a friend an image from a small cove beach, near where I live in County Kerry. Admittedly the image was a set-up job. My own joy at being physically present in this remote and beautiful place was also feeding off the distance and desire of urban others. The friend messaged back with a barely concealed worry emoji, alarmed that the lurid green within my bucolic image was probably algae bloom gorging itself on nitrogen run-off. Suddenly I didn’t feel so joyful. More floating fish swam to mind. It began to rain.

Installation view of Laura Fitzgerald, I have made a place, 2021

Courtesy of the artist and Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

MW: Your new publication, The Restless Bogman (2021), is a short story that conjures a rural figure that haunts the artist-protagonist in a foreign urban setting. He is at once enigmatic and a nuisance, tethered to a distant rural climate and environment. Urbanites often think of rural escape, to the beach or the mountains. Is the lure of the rural a frustration for you to resist or navigate?

LF: I have to say it’s an awful nuisance. I find it incredibly difficult to focus when the weather is good in the countryside. It also can be pretty bad in the city/urban landscape. Evil Dublin, Evil London – I project a mood onto cityscapes depending on the weather, taking them as a displacement site from Eden and therefore from nature itself. I often felt that I have some innate angst that comes to the fore in good weather, a kind of visceral need to be at something useful. I don’t exactly know what the useful thing is, but something like stone gathering, or wall building, or digging is a good place to start. Maybe it’s a kind of grounding I’m after, like getting plugged into nature again. The Restless Bogman started to form in early 2020 during the first lockdown. As the restrictions kicked in, the weather began to get nicer – I found it nearly unbearable to be in our apartment and started to funnel my own frustration and sense of claustrophobia into a story about the Bogman character. It was a way for me to look at my own behaviour with an objective view of my own madness: what he (me) did and what the artist (me) did to manage him.

MW: Your recent exhibition at Crawford Art Gallery, I have made a place (2021), combined drawings, metal and fabric forms, audio, and video. It consistently brought a sense of joy to visitors, who smiled and laughed at the unexpectedness or familiarity of what they saw and heard. Can you say more about what it means to you to create an immersive multimedia environment?

LF: I love ideas of worlding and immersive art, since seeing artists Laure Prouvost and Pipilotti Rist for the first time in places like London and New York. When I encounter artists like this it makes me feel ok again in the world. The best (a very subjective best – not an art-historical one) has made me feel inspired, good, seen, understood. It has made me laugh. I would like my work to be able to do these things if possible. The worst kind of art for me is work that fires a hot flush of jealousy to my nerve centre. It’s normally art that is somehow shouting loudly like an obnoxious person at a party whom I would like to slap in the face. I don’t want to make work like that. The bale piece (After the Spin Cycle) was an attempt to approach this idea, thinking about ideas of scale and superstardom. Like biggest is bestest. Not that monumental work can’t be great. I adore Phyllida Barlow’s work, but somehow I think she would be pretty sound at a party.

MW: You’re currently working on a new series of drawings featuring rocks and stones in supermarkets buying land. There is a similar absurdist humour in your recent video work Searching for Robin (2021) as well as the Zurich Portrait Prize shortlisted Portrait of a Stone (2018). This finely balanced tone is disarming, refreshing in its unexpectedness, and often laugh-out-loud funny. Is this an intentional strategy or just a very happy natural voice?

Installation view of Laura Fitzgerald, I have made a place, 2021

Courtesy of the artist and Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

LF: Not so long ago I found supermarkets to be a place of deep unsettling anxiety. The pinnacle was taking trips to Costco with my mom to buy groceries when she lived in the States. These trips would start as a voyeuristic prospect: supermarket tourism. I would put on my USA sweatshirt and grab a trolley, only to be assaulted by epilepsy-inducing rows of seventy-five-inch TVs, gargantuan pecan pies, aisles of animal: hunks and chunks of fat and flesh. Trays of pink and plumped shrimp tunnelling into my brain. It was an altogether unpleasant experience. My new drawings of anthropomorphised rocks are buying up three for one offers in a frenzy – rivers, glens, mountains – pushing supersized trolleys with lardlike quantities of dark brown soil inside. The same look of frozen despair on their rock faces as on mine in the fifth largest retailer in the world. But I’m not strictly a nihilist per se – I’m just trying to remember a time before the giant supermarkets landed in our towns and cities. I would like there to be a small shop in my village. I think that would help a lot.

I think my natural state is probably a kind of constant unease – one I’ve trained through all sorts of interventions to calm down and cheer up a small bit. I’ve found over the years that humour has a miraculous quality to it, a real joy, a rupture in a net, a place of unfettered freedom. For me this is a life raft in an increasingly grim image of human life I otherwise might drown in. Thankfully it’s in our culture in Ireland. To my mind, Father Ted is the most avant-garde and inspiring example of dark humour in our time – how else can you possibly deal with repression, pain, control, brainwashing, and abuse? The creators of Father Ted found a way and I think my generation are all the better for it. Though I think we might have to find a similar way out of the place where we are now.

Laura Fitzgerald is an artist based in Kerry. She works in video, drawing, text, and installation. Her work is supported by the Arts Council Visual Arts Bursary for 2021–22.

Michael Waldron is an art historian, literary critic, and curator. He is currently the Assistant Curator of Collections & Special Projects at Crawford Art Gallery, Cork.

This Q+A was originally published in PVA 13.