Just weeks before Duncan Campbell was awarded the Turner Prize in December, an exhibition of his work including the film for which he was nominated opened at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Dublin. Alongside the prize-winning It for Others (2013), the show also includes Bernadette (2008), Make it new John (2009), and Arbeit (2011) – three portrait films that examine a range of concerns relating to representation, economy, history, and politics.

The films are showing in four rooms: Bernadette and Arbeit in adjoining spaces on the first floor in the South East Wing and Make it new John and It for Others in the Gordon Lambert Galleries. I saw Make it new John first as it was just about to start as I arrived. An absorbing and multifaceted piece that was co-commissioned by The Model, Sligo, the film features a diverse selection of archive and found footage, and has amassed Campbell well-deserved praise. In one respect, it is a study of the quintessentially American rise and fall of car manufacturer John DeLorean, a boy-wonder at General Motors who went on to create the vehicle that became Doc Brown’s iconic time machine in Back to the Future, but whose West Belfast factory went bankrupt in the early ’80s when government funding lapsed and sales of the gull-winged automobile failed to take off. The four-part film contains a great deal more though, with an opening sequence that offers a vision of DeLorean’s impoverished adolescence, and a staged Beckettian endpoint that enriches the idea of him as what Martin Herbert describes as an ‘American Icarus’, who not only believed in his own myth but also managed to sustain it long after his crushing downfall.[1] As Campbell neatly describes it, the story ‘reverberates endlessly’.[2]

Duncan Campbell

Make it new John

2009

Film still, 16 mm film and analogue video transferred to digital video, 54’

Courtesy of the artist and Rodeo, Istanbul/London.

Campbell also employs archival material from a range of sources to unearth new perspectives in Bernadette, another film that poses as a kind of biopic on one level but functions more effectively as an examination of how the past is recorded, and the ways in which the image of a public figure can be shaped and distorted by mainstream press. The film also conflates the personal with the political in an intriguing way, juxtaposing footage of Bernadette Devlin, the Northern Irish ‘speechifier’ and socialist Republican, with impressions of what another, more introspective side of her life might look and sound like. Using a number of techniques to achieve this, Campbell’s objective is ‘to run against the grain of most documentary film where any subjective feeling is conventionally concealed’.[3]

In the opening sequence, for example, Campbell uses his own footage of grit and detritus followed by close-ups of what we are led to believe are Bernadette’s bare hands and feet before the film moves into clipped, muted extracts of her restlessly listening to another person we never see. This conjures up an entirely different effect to when we see her directly after this in a number of archival segments that capture the extraordinarily eloquent and quick-witted Bernadette responding to journalists’ questions and vociferously instructing other street fighters how to take action. In the final segment, a narrator reads from Devlin’s autobiography, The Price of my Soul (1969), but this suddenly moves into text of a markedly different tone written by Campbell. As in the last sequence of Make it new John, this sequence is staged, but it is made problematic here by the way it imposes on a fiercely political, unabashedly confident young woman a distinctly less self-assured persona. The film succeeds, however, in foregrounding the overlooked nuance of Devlin’s socialist rather than sectarian agenda, in seeking to represent the rights of working class people in Northern Ireland regardless of religious affinity. The recurring use of pauses and black spots on screen also highlights gaps in official public records of this period, and sits compellingly alongside Campbell’s use of ‘outtakes and [of] the marginal aspects of Devlin’s story (…) taking the minor episodes, the parts of continuity between the main points’ to construct something that is multilayered rather than comprehensive.[4]

Duncan Campbell

Bernadette

2008

Film still, 16 mm film transferred to digital video, 38’ 10’’

Courtesy of the artist and Rodeo, Istanbul/London.

Largely made up of still images from the German federal archives, Arbeit is an essay film that relates the course of German economist Hans Tietmeyer’s little-known but highly influential career as former president of Deutsche Bundesbank, and as one of the key figures behind the European monetary union. The viewer is presented with a plethora of information, all addressed to Tietmeyer by an anonymous and omniscient narrator (a device Campbell uses in three of the exhibition’s four films) who provides an outline of the bureaucrat’s upbringing in Westphalia, from his prestigious university education to his move into international banking. The hefty subject matter the film addresses – Germany’s role in the global economy after its postwar boom, the rise of the markets, and the euro zone debt crisis in 2008–09 – is in curious contrast to the film’s intimate form, a form famously employed by Chris Marker to examine the facets of human memory in his 1983 film Sans Soleil. The photos Campbell uses, almost all of which are black and white (another Marker influence), are illustrative but not in any literal way: we see images of trees, then black smoke against a grey sky, a woman standing at the window of a shoe shop, and a pig laying in muck. Books signalling Tietmeyer’s perspective are held up to the camera, including Friedrich von Hayek’s The Road To Serfdom (1944), but we never see Tietmeyer himself. The portrait that does stand out is of former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt in which he is photographed from below, studiously reading while smoking. This is made distinctive by the way it slowly and alarmingly appears to deteriorate before our eyes, drawing an enduring image of decay that mirrors the European economic crisis still plaguing us.

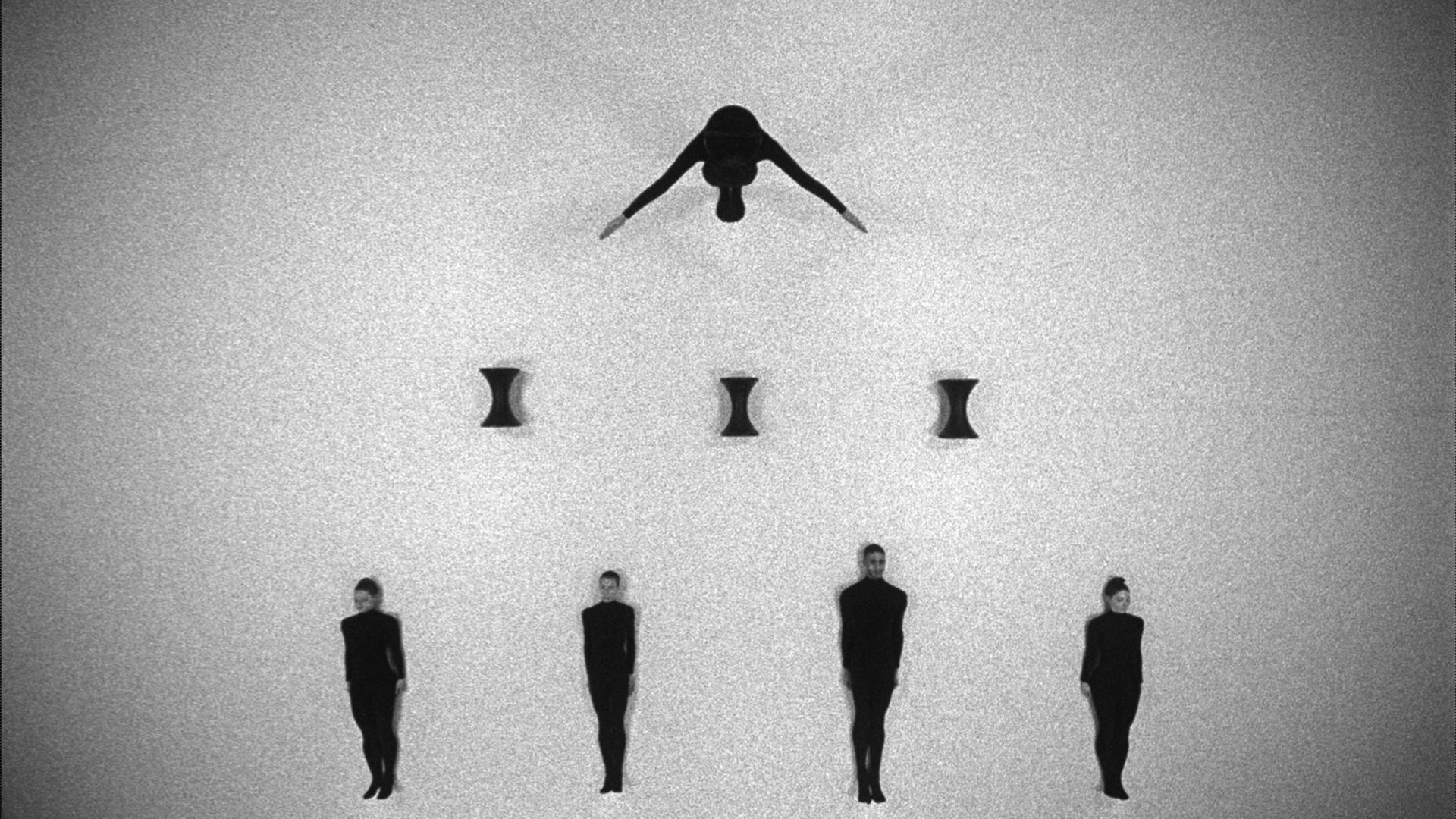

The Marker influence nascent in Arbeit is more fully developed in It for Others, another segmented work, the opening of which is a direct response to Marker and Alain Resnais’s Les statues meurent aussi (1953), a film that looked at the ways in which the meaning and value of African art has forever been altered by colonialism. The second part of the film marks a new departure for Campbell who, for the first time, collaborated with the Michael Clark Company, to offer an interpretation of Marxist economics through dance. This highly stylised, monochrome sequence shot entirely from above, sees several lithe figures dressed in black arrange a selection of props on a flat white surface, gradually building a series of statements, the most striking of which equates ‘Measure of Value’ to ‘Means of Circulation’.

If that sounds vaguely inscrutable, by contrast, the third section of the film, which highlights a tendency for anthropomorphism in product advertising, is wittier in parts. After this, the film moves into a fourth section that conveys one side of a correspondence between two friends we become acquainted with through images on the front of their postcards – of an empty hotel room, a wine reception, and an unpeopled metro station. Recalling Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1977), this was the most effective part of the film for me, but there’s no doubt that it perches somewhat awkwardly alongside It for Others’ other far-reaching concerns, which, in a final section include an analysis of the over-reproduced image of Republican Joseph McCann taken during the Battle of Eliza Street in 1971. The iconic, tenebrous photograph of McCann seen crouching beneath a flag holding a rifle in his hand and looking at the street ahead of him in flames has, the film recounts, been printed on merchandise so mindlessly that it has completely perverted the complexities of the struggle it originally attempted to convey.

Duncan Campbell

It For Others

2013

Film still, 16 mm film and analogue video transferred to digital video

Courtesy of the artist and Rodeo, Istanbul/London.

With such in-depth discussion of how art and imagery can be misappropriated, it follows suit that nothing should hang on the walls of the space outside the screening room for It for Others. There is, however, a selection of visual material on display outside the Bernadette and Arbeit screening rooms that draws out some of the ideas examined in the films themselves. On the walls outside Bernadette for instance, there is a bus timetable and a poster in red and white that reads ‘Falls Burns Malone Fiddles’, a Belfast catchcry that Campbell used as the title for his 2003 film. Outside the Arbeit screening room is a selection of ephemera, including posters warning of inflation and a photograph of a car crash, which are pinned to a cork board as though they might be disparate pieces of evidence in a police case that is still in the process of being constructed.

This aspect of the exhibition raises an awareness of the gallery surroundings, a gesture perhaps towards addressing pertinent questions about how best to show longer film works in an exhibition context (two of Campbell’s films run for over fifty minutes). These are questions Campbell has raised about his work. In a 2010 interview, he described his desire to create ‘a consciousness of the space’, something which has certainly been given consideration here.[5] On this occasion Campbell asked: ‘What does it mean to show a film like the one I have made [Make it new John] in a gallery space? Is it simply a de facto cinema or do the screen and all the other apparatus become sculptural objects because they happen to be in such a space? How does it relate to a tradition of expanded ambient film?’[6] Campbell’s films showing at IMMA are not ambient works like, for instance, his film O Joan no (2006), which has no linear narrative or formal structure and is always shown on a loop with no listed timings. The films at IMMA require a much more cinema-like approach in that it is Campbell’s preference for viewers to see them uninterrupted from beginning to end, a preference indicated by the listed screening times available on the IMMA website and in all the exhibition’s accompanying texts.

Unsurprisingly, the question frequently posed to Campbell now is whether he anticipates moving in the same direction as former Turner prize winners Steve McQueen and Sam Taylor-Wood by turning his attention to a more mainstream filmmaking practice. We’ll have to wait and see.

Alice Butler is a writer and film curator.

[1] Martin Herbert, ‘A Voice, Not Your Own,’ in Duncan Campbell (Glasgow: Tramway, London: Film and Video Umbrella, and Sligo: The Model, 2010), 4.

[2] Duncan Campbell, ‘Make it new John: Belfast Exposed,’ YouTube video, 4:06, posted by ‘Culture NI,’ January 27, 2011.

[3] Tobi Maier, ‘History through Peripheries,’ Mousse, no.18, http://moussemagazine.it/articolo.mm?id=77.

[4] ‘Duncan Campbell in conversation with Daniel Jewesbury’, Vimeo video, 34:55, posted by ‘BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art,’ January 15, 2009.

[5] Duncan Campbell in conversation with Melissa Gronlund, in Duncan Campbell, 49.

[6] Ibid.