Curated by Michael Dempsey.

Karl Burke’s work at The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin was part of Into the Light: The Arts Council – 60 Years of Supporting the Arts. There were similar large scale exhibitions in Cork, Limerick and Sligo, where pieces from the collection were shown alongside newly commissioned work from three other emerging / established artists: Mark Clare (The Crawford in Cork), Emmet Kierans (LCGA in Limerick), and Seán Lynch (The Model in Sligo). Also, an extensive catalogue documenting this period of The Arts Council’s history was published to coincide with the opening of these exhibitions.

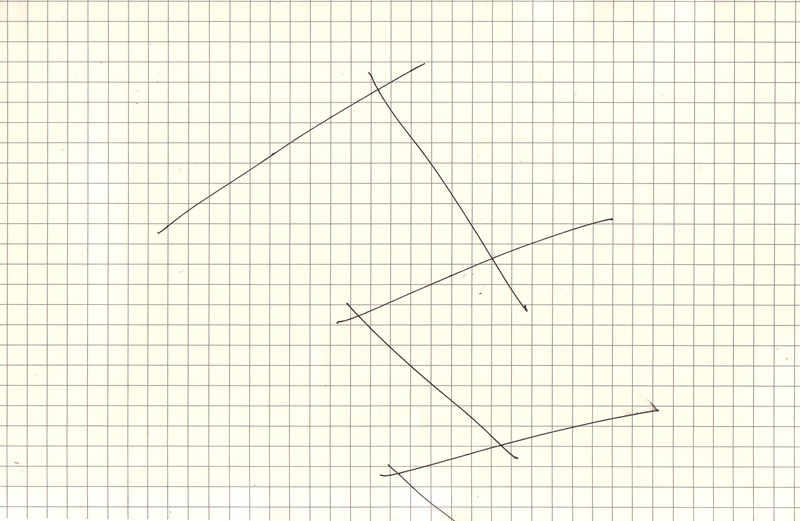

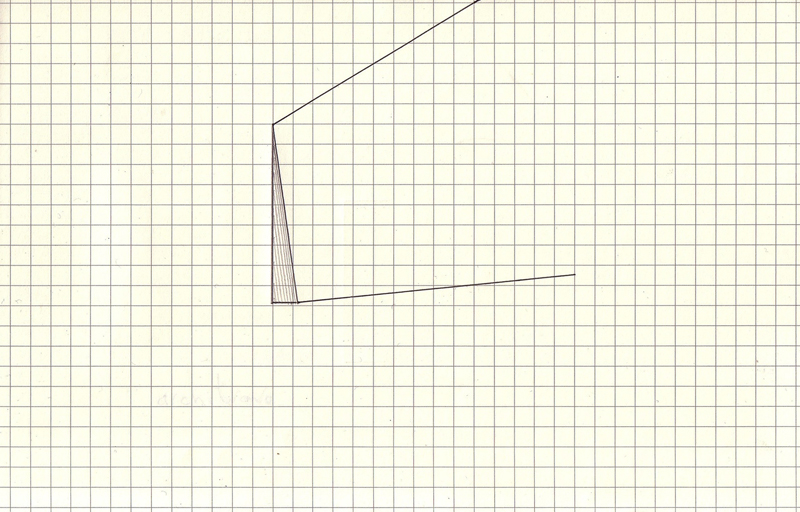

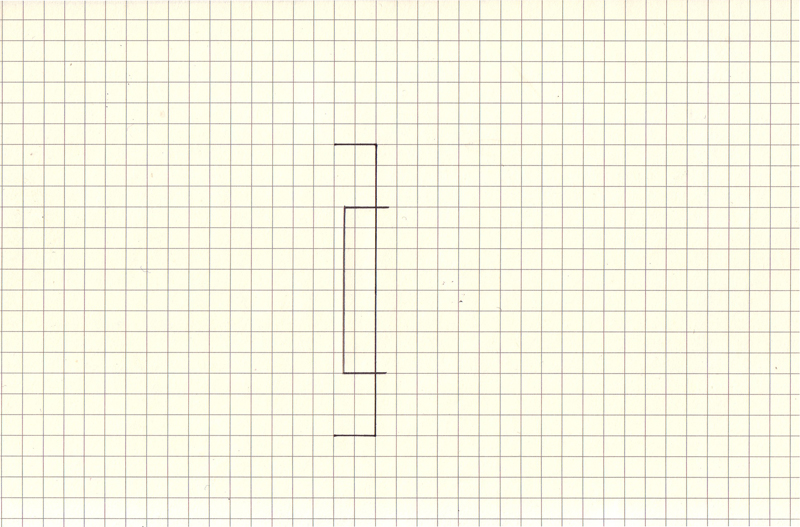

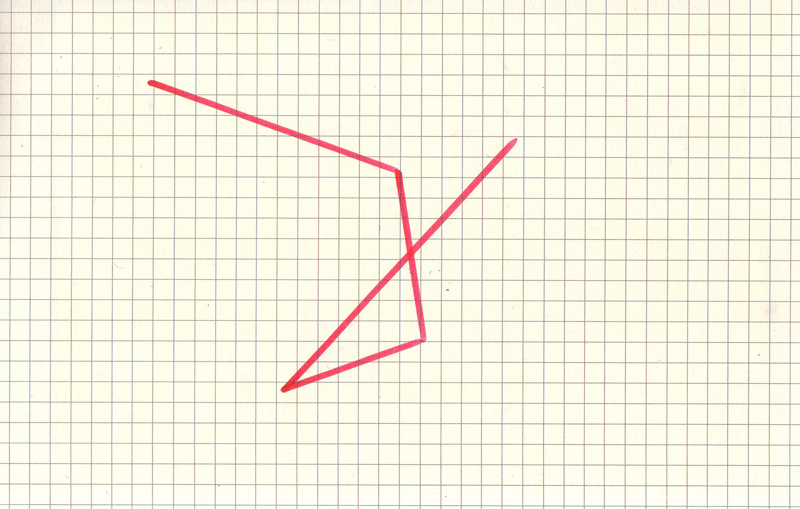

My focus here is on Karl Burke’s Arrangements in the Hugh Lane, which comprised a series of modular ‘minimalist’ objects arranged in three of the four first floor gallery rooms. His work rested among and framed the other works being shown from the collection. I visited the show a number of times and made sketches and drawings while and after I was there, and took some photos too, not of the work itself, but of things that seemed ‘right’ to photo after viewing the work – despite the photos being merely taken with the camera on my phone. I have decided to put some of these with this text, as they were, in a sense, generated by the work and I see them as belonging to and perhaps even aiding this review / response.

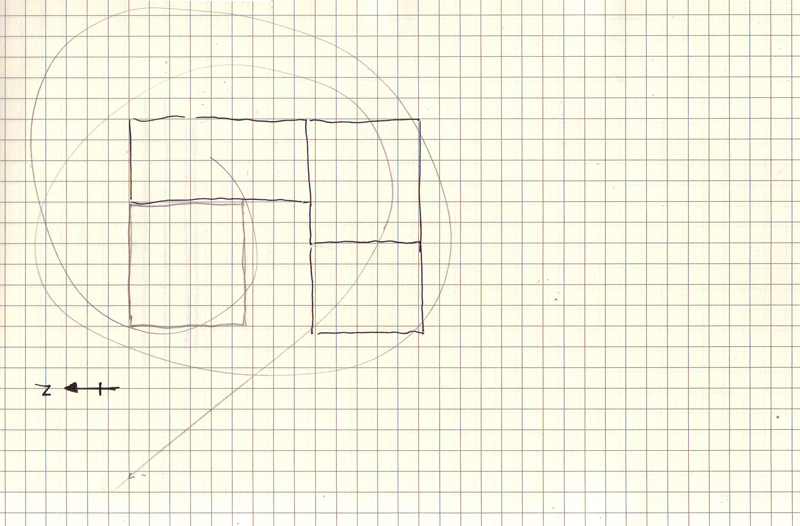

The first arrangement comprised two, slim, black, 8ft tall, rectangular steel frames about 1:2 in ratio. They stood on their long sides, hinging off from the sides of two of the doorways of the largest gallery room. These frames in plan view would approximately indicate two parallel, diagonal line segments cutting across the room. They framed the other works in the room, they framed space, they framed oneself, they framed time – personal, historical, cultural, etc. One could walk through them and around them, but one could not take both of them in at the same time. Either your eyes had to move over and back, refocussing between each object, or you had to change position in the room, only to find yourself denied there too. Eventually you realised that you could not even apprehend one of these frames at once, in a truly complete sense – you were left with just black line fragments in space.

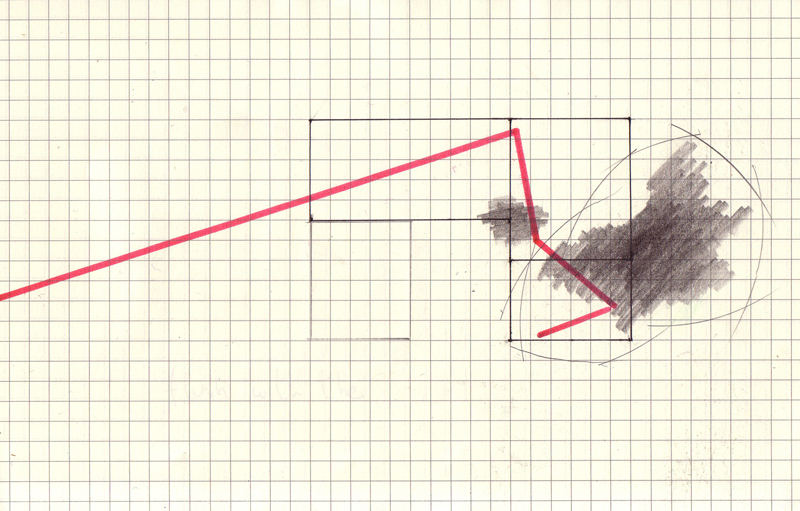

In the second room a small black steel sculpture leaned against the far wall to the right of the doorway that led to the third room. This sculpture was of a seemingly similar material to the rectangular frames in the previous room. It was about 5ft tall and looked like a right hand square bracket. As I walked past it, and through the door frame, and then into the third room, there, leaning against the corresponding wall of this third room, was a reversed version of the square bracket sculpture I had just left behind leaning against the wall in the previous room.

Also, to the front of this third room, extending perpendicularly from the top third of the vertical part of the architrave around the window was a white-timber sculpture comprised of three square frames, of equal size (about 4ft square) arranged, like steps, from wall to floor. When you stood back from this piece, the inside faces of these three modular squares (which were painted an impenetrable matte black) started to fling perspective lines and vanishing points out southward and skyward.

Returning to the second room I stood in a position to the back left of it, where both of the small, black, steel bracket pieces were visible at once. Standing still, and again moving my eyes, refocussing from one to the other, over and back, my experience of time started to collapse into space – a space where an absence was held up.

These things then started to become objects that emerged into this absence, this gap, left behind by language – body language, descriptive, verbal, written language, the visual language of colour, scale, texture, etc.

Within this gap the objects then started to settle somewhere between being separate and having been put apart.

Coincidences between the sculptural pieces, the building itself, the building’s architectural details, and the other artworks sharing that space and time started to become coordinates of memory – a series of fleeting constructions that gathered elucidations of themselves to a place that was itself unreachable, and that I was unable to draw upon.

I then stood at the doorway between the first and second rooms and looked back down through the space that opened up between the two large offset rectangular frames.

Adrian Duncan is a Dublin-based artist, writer and engineer.