I am writing this in the spare room of my house that I rent with my girlfriend and her dog. The table I am writing this upon was left to me by my grandmother. It is an old writing desk, dark, smooth, hardwood. The table can be taken apart, has two columns of drawers and a table top. When you sit to it, the gap for one’s legs is quite narrow. There are two rounded, ornate handles on the drawer doors, some of the handles are chipped or broken off and on the table’s surface there are many scratches and two small, hollow, circular plinths for inkwells. Sitting in one of the plinths now is a small chunk of wax that my grandfather would have melted down to stamp and seal an envelope. One end of this dark red stub of wax is smooth and looks as if it had been snapped off, the other end is charred, deformed and mottled black from the smoke that would have swirled around it.

The house that I live in is terraced and built with artisan brick. It has a timber first floor, a pitched, trussed roof and is over a hundred years old. Two up, two down. On one side of us lives a family of between two and eight noisy Georgians, and on the other a doctor who we barely know is there except in the mornings or during the night or in the middle of the day when her electric shower roars.

Some mornings, when I walk down the narrow staircase of our house, I see intrusions from the outside world. A finger print of light reflected from a window of the apartment block across the street glows on the stairwell wall. When I see these oblongs of faded light, I complete a momentary four-point contract with the sun, that window, the wall of our stairwell and the backs of my eyes. It is a contract with sub-clauses in time, space and seemingly random, human, built decisions.

Our house is one of twelve in a small square behind Manor Street, Stoneybatter. The road that leads from Manor Street to our square is called Arbour Place (Chicken Lane) and is full of cats and horses and cars and shouting. It leads up to a corner where an old milestone stands. Apparently Patrick Kavanagh, sozzled, would sit there and write. It connects Dublin Dublin to Viking Dublin. North west of our street there is a sprawling warren of old artisan brick cottages and two-storey terraced houses with street names like Olaf Road, Viking Street, Ivar Place, et cetera.

A friend of mine bought a book of maps a number of years ago in the Chester Beatty library. They depict Dublin at different stages over the last eight hundred years. Being aware of my interest in maps, he passed them onto me for scanning. I carried this out on a large A0 scanner at my old work place, a consulting engineers office at the top of Prussia Street, which is a continuation north of Manor Street. [1]

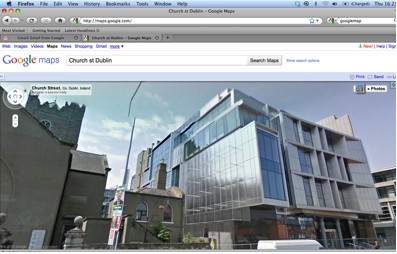

The last building I carried out a structural design on before leaving this company in 2008, was a vast seven-storey office block on Church street, about three streets east of Manor street. Now it sits empty and – though I couldn’t think of a more hubristic name if I tried – is called Kings Building (no apostrophe, at the client’s request). It is a large glass, curtain-wall, brick and cladded structure that could be from anywhere. I know things about it like:

* The building has seven storeys, a basement and a commercial rental floor area of over 15,000 m2.

* The column grid is predominantly 12m x 8m.

* The bolts in the beam to column junction on the fourth floor at grid line junction K/4 are 4no. M20s gr8.8.

* The large movement joint across the middle of the building allows for 40mm of thermal expansion and contraction. (In effect, the building is like a set of vast, slowly moving lungs.)

* The fifty meter trusses that span over an informal famine time graveyard theoretically deflect 50mm at mid-span, when fully loaded.

* The water table is approximately 4 meters below the underside of the basement slab.

* That John, the cockney caretaker, who pads around these floors alone each night, wants to retire at 60 and move to Benidorm.

Beside it is St. Michan’s Church and to the rear of it runs a wall that is over four hundred years old. It is a patchwork of material from different eras and wants to fall down.[2] In the basement of the church there are some open tombs with perfectly preserved cadavers in them. If you take part in the church tour, you are permitted to touch one of the dead – a large crusader whose legs were snapped so as to fit him into the coffin. Thirty feet away from him, and more importantly on the other side of that old wall, are the informal graves of hundreds of famine time victims.

When we were clearing the site at the start of this job in 2006, there was a full archeological dig carried out revealing small graves, foundations, walls, bones, pots, utensils, et cetera. These were unearthed, documented painstakingly, removed and dumped. Two years later, when the building was almost complete, I stood up on the roof of the seventh floor and gazed across the city. The roof-scape of the city is a liar. The road up past Kings Inns is long and steep and if you were to trace a horizontal line from the road level at the top of Constitution Hill across to the sea you would meet the top of Liberty Hall. But there is no way you could know this from the road. This sort of objective knowledge is not available and is not of interest as one noses one’s way around the contours of the streets. From this elevated position, the city unfolds to you in falsity after falsity, the shape of the land can be no more determined than its history. This re-writing of the land to city reduces the city to an over-worked and crossed out sentence of garble. All one gets is an approximated generality, the specifics of the spoken street is lost.

As I continued walking around that near completed building, I thought of the flat floor plans the architects and I had pored over in their offices for months before we started to build. I went to the places in those plans that had thrown up specific spatial problems and stood in the new material elucidation of those spaces. I thought of the gleaming walls, the slabs, the beams, the pinging columns, the foundation pads, the piles, the water, the earth.

My great grandparents ran the famine work house in Longford until it burnt down in the early 1900s. Then they built and moved to Ivy Villa, a house on a large farm with a forest on one side and fields that run down and ripple into Lough Ree on the other. My grandfather (my mother’s father), who was brought up in this house, met my grandmother in London during the Second World War. They married in Oxford and after the war moved back to Ivy Villa where my mother and my uncle were born and raised.

The photograph in the frame above was taken in and around 1910. My grandfather, James Farrell, is furthest to the right. The house behind is Ivy Villa. The picket fence is gone and where they are standing is now a yard where my grandmother once kept chickens. It is, obviously, a family portrait and has an eerie, almost Victorian love-less-ness to it – my family and my home. I don’t know who took the photograph or who designed the house, however, I do know it was one of the first houses in Longford to have electricity and running water. The ladder on the right hand side of the picture leads up to the water tank that was used to collect rainwater for drinking and washing. When my sisters and brother and I as children, would visit my grandmother, the water, we decided, tasted strange.

In February 2004, after I had just moved to Edinburgh, my grandmother died. On the night of the removal her coffin was brought downstairs, along the hall, past the sitting room where this desk then sat and into the dining room where she was passed through a window to some men outside. The windows, as you can see in this photograph, slide up and down. Only recently have I been back in that house, and when I did revisit, despite there being a few lights left on, the place felt utterly empty. It only struck me at the time the strangeness of her being passed out through the window and I concluded that whoever it was that designed this house, designed it only for the living.

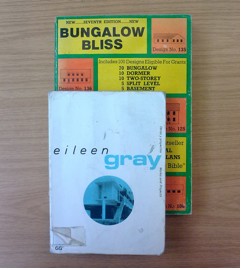

My father is (also) an engineer. He designed and built my/our home house in Ballymahon, south county Longford. Our house is a bastardized mixture of a Bungalow Bliss design and his imagination. It has two very large front windows, a wide set of concrete steps and it has been added to considerably over the years as our family enlarged. Bungalow Bliss was a book devised and self-published in the early 1970s by an architect called Jack Fitzsimons, who then worked for Meath County Council. The book became a bestseller and has been amended and re-published over and over again through the 70s, the 80s and the 90s, however, it is now out of print. The book worked for a number of reasons, it was straightforward and easy to read, the information in the book gave you a number of designs which you could choose from, and vague siting contexts for these designs. The full size drawings of these designs were sent to you then you carried out the planning permission with your local County Council via the guidelines provided in the book. At the time, there was a lot of space in rural Ireland and a generation of young couples with some money and a need for a home. There are thousands of these houses all over Ireland. The construction was cheap and simple and drainage was of little complication. As designs, some can be depressing, even kitsch and they are generally looked upon sniffily, but for me, they have a sort of humility; they represent and express an unspoken form of non-canonical, rural Irish Modernism. [3]

When I was young I liked going into my father’s office to look at his huge, precise drawings, the t-squares, the ink, the razors, the rolls of paper, the pencils, the cranked lamp, the smell. I would talk very seriously with him about his work, not understanding a thing, other than that I wanted to do this. Whatever this was. He worked for a number of years for Longford Co. Council, then, bored out of his mind, he left, set up his own business, and changed his car to a small old beat up, green and embarrassingly ascetic Audi 80. By the mid-nineties he was building houses for sale all over Ballymahon town, industrial units, more houses, bungalows, two-stories. He bought The Mill, a then large, crumbling, seven-storey stone structure, down by the River Inny, that came in two blocks – in school, you’d take your girlfriend there for a lunch-time “shift.” He had plans to put apartments in it. However, he had moved altogether too quickly, having preempted the recent building boom in rural Ireland by about five years and subsequently ran out of credit. He sold everything and stopped building but continued working as an engineer for years, then he went back to university to study music.

Now he teaches piano, though he does not play very well himself, and on Tuesdays comes up to visit us in Stoneybatter. Occasionally, he helps me with jobs for people who want small extensions designed to their starter homes in the suburbs around Dublin.

FOOTNOTES

[1] During a lunch break at work recently I had a look through the secondhand book stalls in Temple Bar and came across a book called North Dublin City and its Environs, it was written by Dillon Cosgrave and published in 1909. It was a small, green, hardback book in good condition, but cynically priced at €65. I flicked through it, took some notes and learned that the book’s previous owner was a J. Geoghan (dated 16th March, 1919) and that Manor street was thus named in 1780 after the Manor of Grangegorman. The Manor in question was owned by a Sir Thomas Stanley (during the reign of King George III). Incidentally the bridge that links this part of the city to the old town centre was then called (amongst its many names before and since) Mecklenburg Bridge, after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, King George’s wife. The then concurrent Prussian King was Frederick II, who was circuitously related to George III (they all seemed related), thus Prussia Street. Further north on Prussia street there now stands, across from Tescos, a shabby bar called The City Arms which, back in the 1780s, was an upmarket hotel where the Jameson’s, a family of whisk(e)y distillers from Scotland, often stayed. The Jameson distillery is still accessible from Bow street along the back of the Church street (ref. Kings Building). Much of the architecture in this part of the city is Georgian/Palladian, with particular instances on Manor street, Capel street and Henrietta street.

I learnt one other thing from the quick glance at this book, that the name Stoneybatter comes from the gaelic Bothar na gCloch and has thus been named for over seventeen hundred years. It is thought to have formed part of the old high king’s Wicklow to Tara highway and as such, according to Dillon Cosgrave, the name Stoneybatter must be granted the palm of antiquity amongst Dublin street names.

[2] An Iraqi engineer and I spent a week surveying this wall in the summer of 2006. It was a mixed photographic, condition and structural survey.

[3] I attended a lecture in January of this year at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) that was given by Brian Dillon and was designed to compliment the then current The Moderns exhibition. Broadly, he spoke of Irish Modernism as being mostly literature based, Beckett, Joyce, Synge, et cetera, and as such we (the Irish) could be considered as important contributors to Modernism in general. Amongst many other things, he made the observation that a lot of postmodern and contemporary artists in Ireland make and have made work which revisited this literary Modernism, examples being Gerard Byrne revisiting Beckett, Declan Clarke revisting Heinrich Böll and John Cage revisting Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.

In relation to John Cage’s revisitation of Finnegan’s Wake, Dillon described this as stemming from a commision Cage received in 1978 from the German National Radio Station. Cage decided to visit (randomly of course) the places mentioned in Finnegan’s Wake, where he would merely record the ambient sounds, snatches of conversations, doors opening, gates closing, dogs barking, et cetera. During the course of this journey, he wrote a letter to a Minna Lederman [*] describing the countryside and the B&B lodgings he was using throughout:

Ireland is poor, but full of modern bungalows …… Many of the new bungalows are designed to be B&Bs. A hallway with bedrooms, the only thing missing is a private bath…..

[*] Minna Lederman Daniel (1896-1995)was a music and dance editor and writer, and a major influence on 20th-century music. In 1923, she was a founding member of the League of Composers, a group of musicians and proponents of modern music. In 1924, she helped launch the League’s magazine, The League of Composers review (in 1925 the name was changed to Modern music), which was the first American journal to manifest an interest in contemporary composers. She served as the sole editor of this magazine from its inception to its demise in late 1946. During this period, she developed the journal’s distinctive literary style and was directly responsible for bringing to readers the literary efforts of significant young composers such as Marc Blitzstein, Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, John Cage, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Roger Sessions, and Virgil Thomson. Following the demise of Modern music, Mrs. Daniel (who wrote under her maiden name of Lederman), continued to write on music and dance. In 1974, Minna Lederman Daniel established the Modern Music Archives at the Library of Congress.

(abstract from the Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.natlib.scdb.200033887/default.html)

NOTES ON IMAGES

1. Scan of map detail drawn by William Duncan, 1821.

2. Image of Kings Building and St. Michan’s Church, from Googlemaps.

3. Image within the notes section is a detail of a cast of a 1:200 model of a Georgian building. The cast was made by Aidan Lynam as part of his Babel project, (currently in the R.I.A.I., Merrion Square).

All other images by Adrian Duncan.

Adrian Duncan lives in Dublin.