Last year, my uncle received a letter from a man in London claiming to be his cousin. Not knowing what to do with this information, my uncle passed the letter on to my mother, who corresponded with him. It appeared that the man was indeed their first cousin. While living in London, his mother – my mother’s aunt – gave birth to him in secret and put him up for adoption. She then emigrated to America, married, and had more children, none of whom knew anything about her firstborn. My mother speculated that the same thing had happened to her other aunt. I suspect every Irish family has at least one of these stories. Sometimes, I think the only real continuity in modern Ireland is its persecution of its women and girls.

This story returned to me as I started looking and thinking about the work of Patricia Hurl. But I’ll admit, when I first read about her exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), I couldn’t quite place her. The name struck a familiar note – maybe, I thought, I’d seen one of her works in some group show at the RHA? I doubt I’m alone in this: despite producing work consistently since the eighties, Hurl has never received much attention, let alone a survey exhibition of this scale. With paintings, drawings and preparatory work made throughout her entire career, Irish Gothic occupies the entire west wing of IMMA. From nearly nothing to a resounding scream – this, in itself, was sufficient to interest me.

In a conversation with the curator, Johanne Mullan, I learned that Irish Gothic happened more or less by coincidence. During a visit to a group show at the Highlanes Gallery in Drogheda, Mullan – much impressed by a few works by Hurl – wondered if she had any more. It emerged that Hurl had much, much more; in fact, she had been making work ever since her college days almost forty years back. But for whatever reason, she never really got much attention after her first solo show and moved into teaching as well as less-commercial contexts. Hurl had, however, documented or kept almost everything she ever made – just in case.

Installation view of Patricia Hurl, Irish Gothic. Courtesy of the artist and the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

Born and raised in Dublin, Patricia Hurl is now in her eighties and lives in Roscrea in County Tipperary, not far from where I grew up. She has always painted. Initially, Mullan tells me, it was watercolours, tacking studies onto the railings around Stephen’s Green. Later, in response to a personal tragedy, she stopped for a time, after which she was encouraged to switch to oils. This change prompted a return to study at art college – at that point, as a married mother of four. Judging from the tone and content of her early works, this was not an easy spot to be in. It seems art college was a place for Hurl to work through her frustrations and to assert her autonomy and creativity outside the domestic sphere.

We are talking here about the late seventies and early eighties. To give you some context, women were now allowed to work outside the home after marriage, but they still bore the majority of domestic work. In 1979 the contraceptive pill was legalised, but in practice strictly controlled and reserved for married couples. That same year, Pope John Paul II visited Ireland, and more than half the country turned out to welcome him. Fifteen-year-old schoolgirl Ann Lovett died alone giving birth to a stillborn baby beside a grotto dedicated to the Virgin Mary in Granard, County Longford, in January 1984. If Ireland was changing, then, that change was slow and slight, curtailed by the enduring stranglehold of the Catholic Church. The last Magdalene Laundry did not close until 1996.

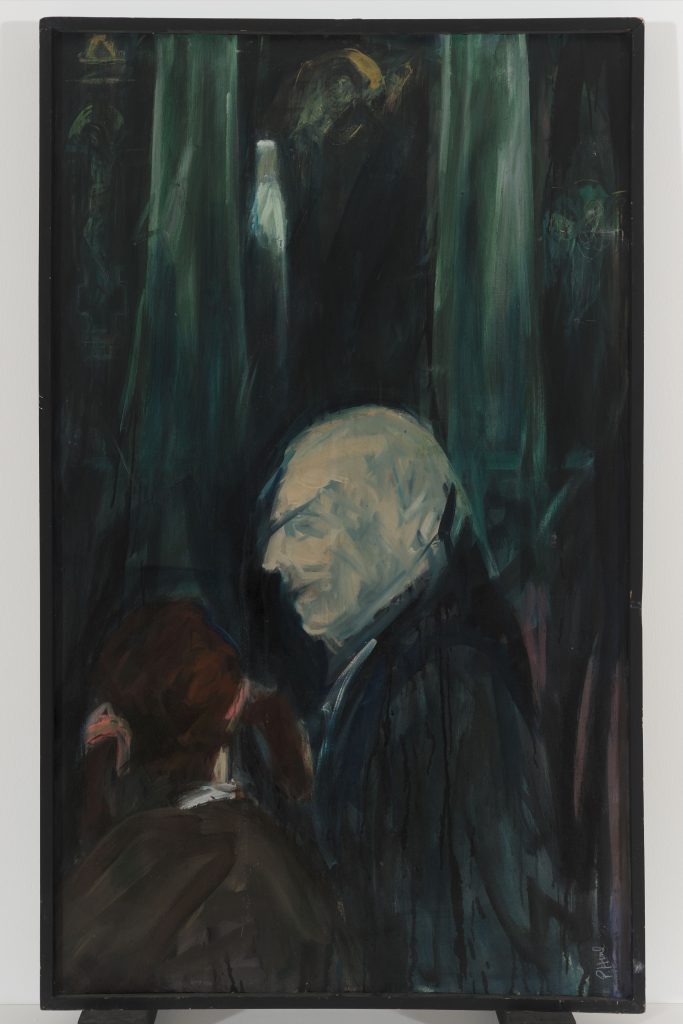

Patricia Hurl, State of Fear, 1985. Oil on canvas, 155 cm x 94 x 4.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Denis Mortell.

Hurl’s earliest works are shaped by the tension – as well, I think, as the accompanying fury – of being a woman and an artist in Catholic, deeply patriarchal Ireland. At IMMA, these early works comprise the majority of what’s on display – starting with her first solo exhibition, The Living Room: Myths and Legions, which was shown at Temple Bar Gallery and Studios in 1989. With this early outing, we can already grasp Hurl’s signature style: a highly expressionist handling of oils; large-scale, figurative portraits in dark blues and greens, with flashes of yellow here and there. When people appear, their faces are uniformly smudged, lending the works an ominous, nearly violent tinge. In them, Hurl captures the claustrophobia of being a woman in Ireland at that time – from the perspective of someone who has had quite enough.

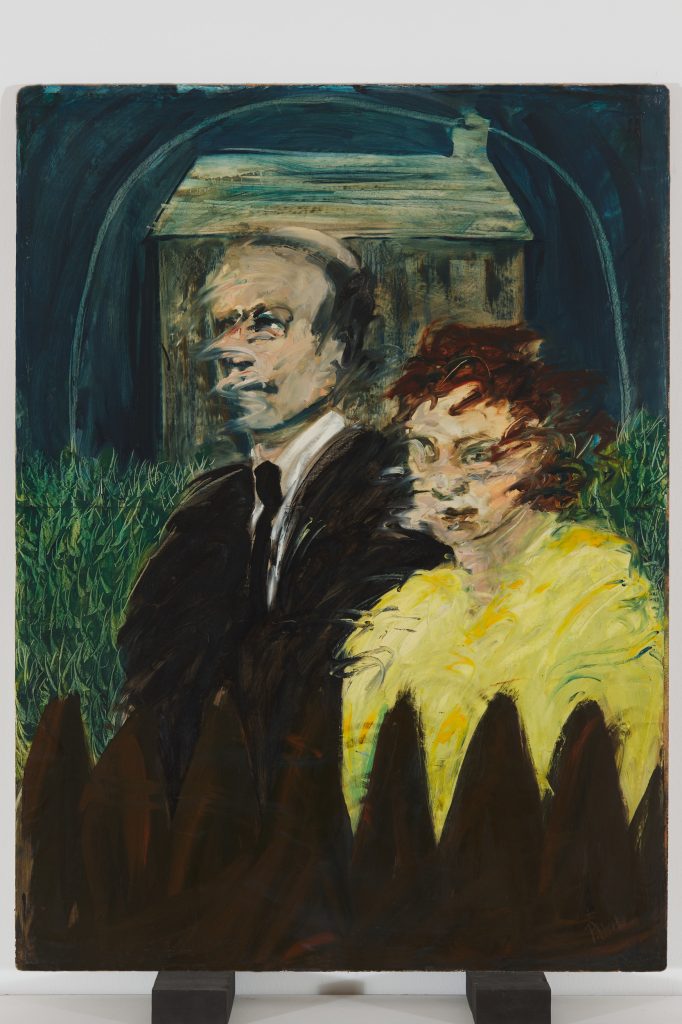

Many of these early portraits depict women alongside men. Hung alongside one another, State of Fear (1985) and Ministry of Fear (1986) are two large portraits depicting an older man alongside a small girl in pigtails. In the former, the man’s blue-tinged face faces us; the girl’s head is closer and turning away. The latter depicts what appears to be a communion scene – I have a similar one, lined up with my sister against the railings of our local cathedral. The man’s big hand rests on the girl’s left shoulder. Both share a visual language. Dark swathes of blue and green, faces smudged to obscurity. In Irish Gothic (Living Room) (1985), a man and a woman stand between a house and a jagged picket fence, their faces blurred and angular. If this is a domestic idyll, it is fractured and full of unease.

Patricia Hurl, Irish Gothic (Living Room), 1985. Oil on paper, 123 × 90 cm. Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Denis Mortell.

In another early painting, Art of Union (Once Upon a Time) (1986), we see a woman – the artist – on her wedding day, holding a rose in her hands. On her left, she is flanked by a suited man, presumably her husband, and on her right, what appears to be a bespectacled priest. Their faces are once again obscured. Either the solemn act has just been carried out, or is presently going to be. Regardless, it is clear that no one seems especially happy. Much like the father-daughter paintings on the other side of the room, the painting is both familiar and uncomfortable. In these paintings, the women appear encroached upon, accessories doomed to act and be represented only in their relation to men. These are the largely unassuming actors of patriarchy, after all: fathers, husbands, and priests, each a participant, by turns active and passive, in the control of Irish women.

In Hurl’s experience, being a woman in Ireland meant endless, thankless domestic servitude. Expressing this, Hurl often takes a dark, humorous approach. In Sunday Rituals (1988), a genteel interior scene, the artist has painted herself served up on a platter on the dining-room table. In another work, Pretty Maids All in a Row (1999), a group of women, some naked, some upside-down, are hung out to dry on the washing line. Hurl is keen to point out the long history of this fate: in a later work, The Sheets Are Laid in Perfect Order II (1997), Hurl reflects on the even worse fate of previous generations, through the life of her mother, who died when the artist was a teenager. While scarcely remembering her, Hurl remembers her mother doing laundry – folding sheets right up until her death, and giving until there was nothing left.

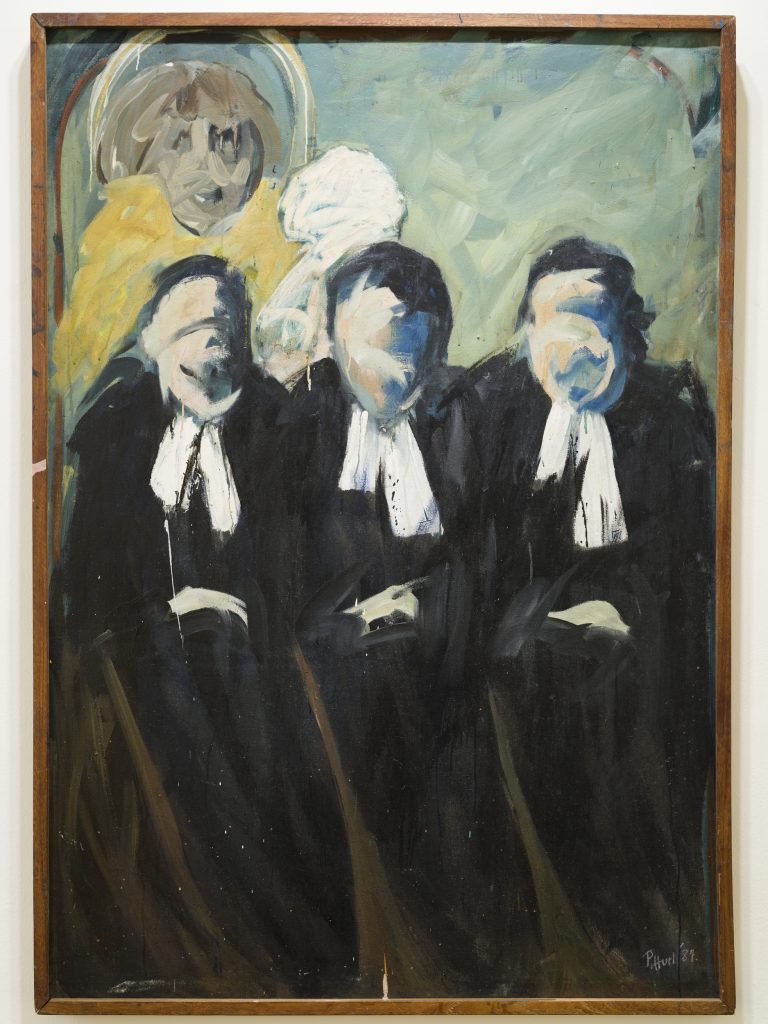

Patricia Hurl, The Kerry Babies Trial, 1987. Oil on canvas, 155 x 109 cm. Drogheda Municipal Art Collection. Photo: Jenny Callanan.

Logically enough, the role of the Catholic Church and its treatment of women also features in Hurl’s work. In her co-option and reworking of Catholic imagery, she casts an unambiguously critical eye on the Church’s continued legacy, namely, curtailing the freedom of Irish women and subjecting them to unrealistic and misogynistic ideals. In Madonna (Irish Gothic after Masaccio) (ca. 1984–85), she reworks the idealised picture of mother and child as a self-portrait, an imperfect and much more plausible depiction of motherhood. Elsewhere, we get depictions of the Fall – the act said to have lumped us all with original sin. Though Catholic teachings have always stressed Eve’s greater culpability in this, in so doing defending their right to treat all women as inherently wicked and in need of being controlled.

In Hurl’s work, Irish institutions are shaped by this fundamental misogyny. One example is the infamous Kerry Babies trial of 1984, in which a young woman Joanne Hayes and her family were terrorised by the local police, convinced – despite contrary medical evidence – that she had murdered the baby found on nearby Cahersiveen beach. In The Kerry Babies Trial (1987) we see three faceless barristers, long shadows spilling down across a wide table that creates a gulf between them and us. There is something predatory about them, almost like they are waiting to pounce. In this, I can glimpse the indifferent power of a state that neither acknowledges nor respects me. Joanne Hayes was cross-examined by men like these for five whole days.

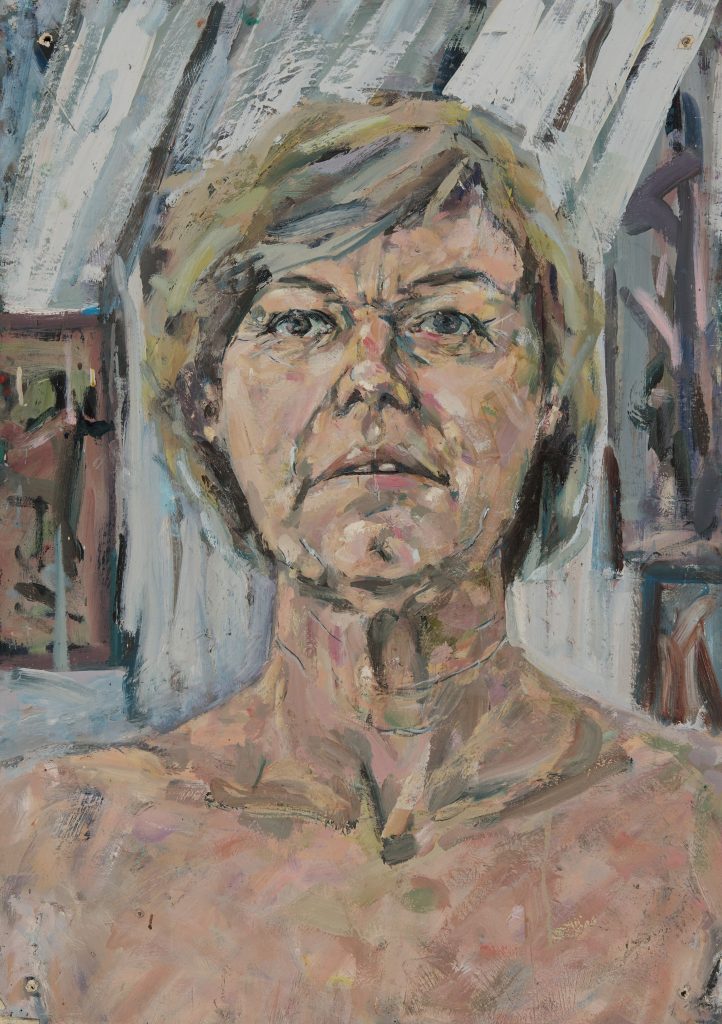

Patricia Hurl, Forensic Self-Portrait (Head), 1993. Oil on board, 84 x 59.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Denis Mortell.

Following a health scare, Hurl makes a shift towards self-portraiture, which makes up the majority of the later works on show at IMMA. The charcoal-on-paper series Eve Factor (1996), for example, sets out to document the threatened body; in another room, the four oil works of Forensic Self-Portrait (1993), take a similar tack, with fleshy, unflinching close-ups of the artist’s body. In Call and Response (1992), Hurl reworks the vagina as an abstract series. The most recent Warrior Series shows the artist – now an elderly woman – wearing a collection of shop-bought and self-fashioned armour. Hurl refuses to become invisible; she will quite literally go out fighting instead.

While certainly courageous in their subject matter, I find it hard to connect with Hurl’s later self-portraiture. Her work is strongest, I feel, when it stays close to the social conditions of its making; in its witnessing of instances of systemic misogyny like the Kerry Babies trial; or, indeed, her own experience with institutions as a mother and wife. While I respect the gesture, I struggle to connect with paintings of body parts, which feel tired and essentialising rather than radical. Indeed, despite my best intentions, I reflexively cringe when I see this kind of work – not because the work is bad, per se, but simply because I think it has dated. The social conditions and sense of urgency that once demanded it – or so I like to think – simply aren’t there anymore. But then I remember that I am formed by a religion that tells me to always see women’s bodies as unnecessary and gratuitous; indeed, has never stopped telling me this.

There is a lot to admire in this exhibition, and I am glad to see Hurl get recognition for a life spent working, more or less, without acknowledgement. As someone who frequently considers the idea of giving up, Hurl’s tenacity just to keep going is in itself an achievement. And certainly, her early paintings have a bitter humour and fury that remain compelling, despite the changes that have since transformed Irish society. As I look at and consider them, I realise that, in some ways, very little has changed. Despite the legalisation of abortion and gay marriage, Ireland – like most Western countries – remains a deeply conservative, patriarchal place. For one thing, care work remains largely the responsibility of women and it is not valued. Our time is still second-rate. Then these paintings make me angry and remind me of the work still left to do.

Rebecca O’Dwyer is an Irish writer living in Berlin. She has been published by Source Photographic Review, Art Review, Fallow Media, Apollo, The Stinging Fly, The Tangerine, and elsewhere.