Petrit Halilaj’s model of his house in Kosova which was rebuilt after the war: They Are Lucky to Be Bourgeois Hens

mixed media, iron & wood;

2008

Image courtesy of the Berlin Biennale.

For the 6th Berlin Biennale, curator Kathrin Rhomberg presents us with the title What Is Waiting Out There suggesting a division between contemporary art and the world outside of contemporary art concerns.[1] Rhomberg presents artists with different positions, frames of reference, and their different relationships with reality from the literal to the abstract. This curatorial aim manifests itself in the works, ranging from the banal to the momentous, from the domestic to those of wars – both known and unknown to us.

Avi Mograbi’s video of Israeli soldiers Details 2 & 3 is illustrative of this, as is Mark Boulos’ aggressive video addressing the local resistance to the invasion of the Niger Delta by Western oil companies in a two-channel video piece titled All That is Solid Melts into Air (2008). The title of the latter is taken from an oft-quoted section of the Communist Manifesto and was also the title of a book by Marshall Berman examining social and economic modernization and its conflicting relationship with modernism: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”[2]

Mark Boulos: All that is solid melts into air

2-channel installation, HDV, colour, sound, 14′ 20″

2008

installation view

photo: Uwe Walter

Image courtesy the artist.

The curator’s question we must consider: how does art affect reality? This is best approached in the Biennale by those works where reality is not taken on in a literal sense but where this gap between the art world and reality is nebulous and ever-changing.

In the basement of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Petrit Halilaj’s delicate, well-considered drawings contrasted with his large wooden house structure and his futuristic-looking chicken houses (They Are Lucky to Be Bourgeois Hens, 2008). His drawings were as much about the actual medium as his subject matter of the everyday, the domestic and the familiar.

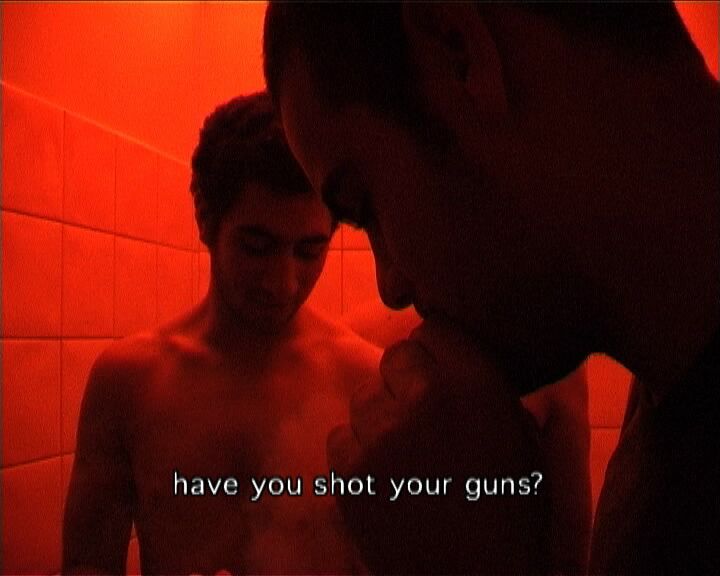

Ruti Sela and Maayan Amir’s uncomfortable Beyond Guilt #1 (2003) – from the video trilogy Beyond Guilt (2003–2005) – blurs the boundary of the artists’ position in the work. They use sex and the promise of it to communicate with young people in the toilets of nightclubs in Tel Aviv. There is an obvious link here between sex, power and violence. Those who saw the artists’ work in the recent Istanbul Biennale will have seen this at play in a much more voyeuristic and sinister fashion with young men. With the work here, we become part of the piece by being witness to events. This is a reality where sex rules. The artists, in order to be a part of this reality, take on personas and the notion of the artist being a separate entity from their work disappears.

Ruti Sela & Maayan Amir: Beyond Guilt #1

from the video trilogy Beyond Guilt (2003-2005)

DVD, Farbe, Ton/DVD, color, sound, 9’30”

2003

Image courtesy the artists.

Phil Collins’ 2010 video marxism today (prologue) is a sensitive documentary-style piece where ex-Marxism and Leninism teachers from East Germany are now struggling to find a new identity. There is a subtext of wondering about why the world changed so quickly and why they now have opinions at odds with the world they must now take on and inhabit. This thoughtful video piece encourages the viewer to see past the facts of the Cold War, and to imagine what it must be like when one’s perception of reality is turned upside down and beliefs – whether they are enforced or not – are stripped away.

This work is part of a wider context as Collins was invited to work on the Artists Beyond programme that was a prelude to the exhibition in the Biennale. Rhomberg invited six artists to respond to local places and publics in Berlin. Collins’ piece is well made. The interviews are pared back and meaningful, interspersed with propaganda footage of a classroom discussion on what it means to be exploited; the experience is enhanced through watching it in a hot room, full of strangers. A non-verbal dialogue occurs that spills into the actual conversations held after the screening. Both dialogues feel real.

The Oranienplatz, an East Berlin square in the area of Kreuzberg, is at once decrepit and decadent, with a crumbling beauty. Rather than forcing this space into being a white cube gallery, the curator has cleverly left, untouched, the cracks in walls, holes in floors, and the graffiti daringly close to works. Some spaces have been made to satisfy artists’ specifications; the overall layout and feel of the space has been carefully considered and is honest – this is particularly noticeable in the attic space. Here we see iron girders supporting a roof that is in some parts tarpaulin and other parts rotting wood.

Phil Collins: marxism today (prologue)

DVD, Farbe, Ton / DVD, color, sound, film still

Commissioned and co-produced by the 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art and the Artists-in-Berlin Programme of the DAA

2010

Image courtesy Shady Lane Production

Image copyright the artist.

MDF walls loosely embrace Ferhan Ozgür’s video work I Can Sing (2008). The walls lean precariously sideways, and in one case do not quite meet the concrete floor. Cardboard and MDF scraps cover the windows. The piece itself, of a woman in traditional Arabic dress lip-synching to the Jeff Buckley version of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, is at first curious, then deeply moving. This may be attributed more to the song than to the video itself.

A garage in Mehringdamm, which holds a large video installation of work by George Kuchar, is comprised of TV screens with headphones, each one showing a different video piece. There is also a projection and graphic drawings. The volume of work is not overwhelming thereby reinforcing the idea that the artist is committed to his subject matter. Kuchar uses and reuses imagery so that it becomes a language, thus lessening the potentially overwhelming room of flickering TVs. Each video plays like a chapter in a long rambling tale about the artist’s experience in a rural area of Oklahoma where he meets odd, but real people, and ponders the weather obsessively. The video shows boredom, frustration and most of all, the artist’s unique and honest way of looking at the world. It is here that Kuchar appears most comfortable in the non-places of anonymous motels and Middle America where he has no status of being an artist but is viewed as part of a particular reality. From the viewer’s point of view, he becomes as odd and as strange as the people and places he is exploring.

The Berlin Biennale has never been a place of hierarchy or exclusion and these pieces mentioned in some way illustrate this. The city plays a major role in every work, creating a context of time, place and a sense of urgency. It is a stimulating interaction with contemporary discourse.

Maeve Mulrennan is the Visual Arts Officer in Galway Arts centre in the West of Ireland.

[1] http://www.berlinbiennale.de/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=141&Itemid=99

[2] Friedrich Engels & Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto p223 Penguin classics 2004.