Plato insists that truth underlies the world of appearances – that we must look beneath the surface of things to find reality. In ‘An Approach to Painting’, a 1942 essay that is also a manifesto, Mainie Jellett seems to agree, explaining that her paintings were ‘based on the eternal laws of harmony, balance and ordered movement (rhythm). We sought the inner principle and not the outer appearance.’ [1] This dichotomy, between appearances and their somehow more ‘real’ foundations, is a central concern within many visual art practices. Paradoxically, it is through a focus on surfaces – specifically the surface of paintings, photographs, and other kinds of image – that Brian Fay seeks to penetrate the meaning of things. Fay’s practice involves an examination of artworks and their material and ontological mutability over time. This forensic process is the basis for his drawing practice, making a body of work that emanates from the historical artworks he examines as a kind of testimony, a personal response to selected, careful encounters. Fay’s own works, and the works he engages with, are enmeshed in a process of mutual revealing.

Plato’s construction of art as mimesis has undergone substantial review, but I can still remember the pejorative of ‘copying’. As a budding, ten-year-old artist I loved to copy, ingraining an image in my mind by making my own version of it. As mimetic gesture, drawing’s combination of the ocular and the haptic turns the drawing body into a kind of machine, calibrated – however sensitively or crudely – to a subject. By overlaying his subject with transparent methods, Fay largely sidesteps this dynamic in favour of a more hands-on approach. Operating on the surface (albeit through facsimiles), Fay closes the gap between the eye and the hand, tracing the grain of his subjects, feeling for the anomalies that mark images over time.

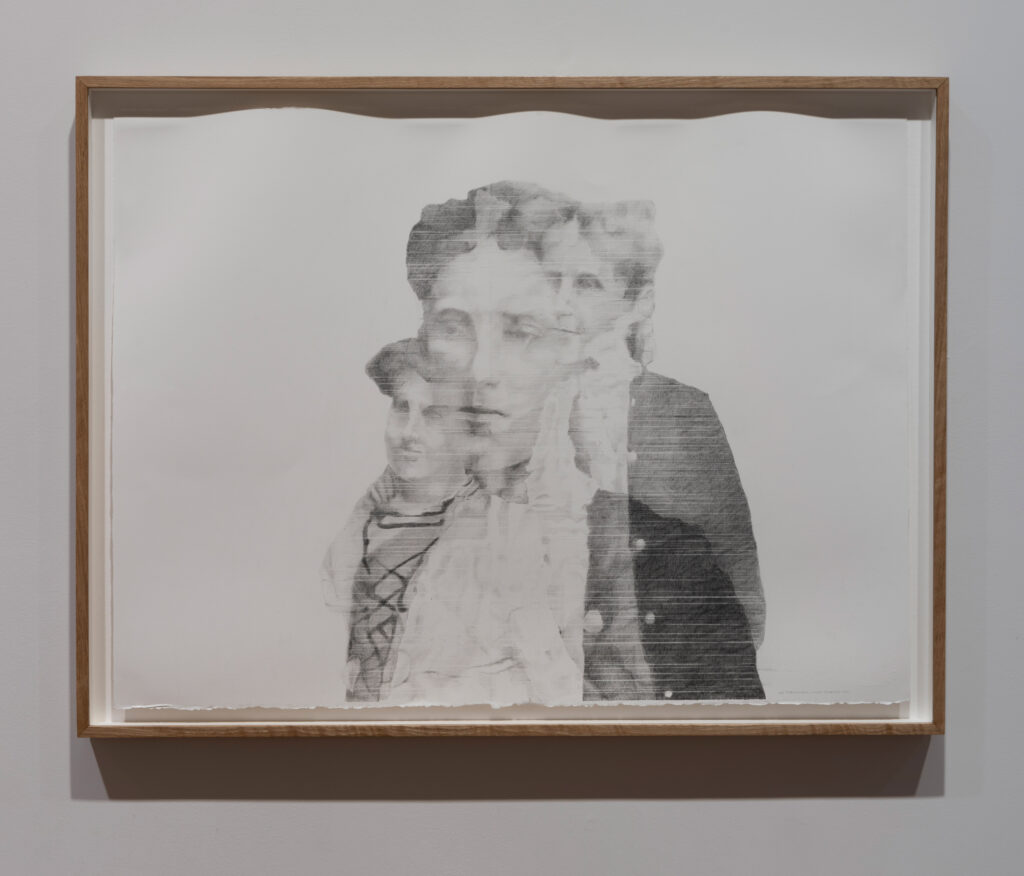

Brian Fay

MJ Transitional Drawing, 2021

Pencil on paper

Photo: Lee Welch

In A Mobile Living Thing, the artist focuses on four small paintings by Jellett in the Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council art collection. Framed works on paper, these paintings are included in the exhibition, alongside two distinct but interrelated series of mostly graphite drawings by Fay. Sourced from photographs, a set of pencil portraits shows Jellett at various stages of her life: from a sixteen-year-old girl to an older artist in various locations and guises. The Ether Series (2019–20), by contrast, is a group of nine densely worked drawings, also made with pencils, but entirely abstract. A single drawing on a roll of paper, Jellett’s small entropy: Rotation and Translation (2021), is eccentrically framed and continues the formal approach of The Ether Series but in reverse and on a much larger scale. A lone watercolour drawing, Rotation and Translation – Entropy – After Abstract Composition 1937 (2019), is also related but distinct. With Jellett’s paintings strategically positioned among Fay’s original drawings, the viewer is encouraged to move backwards and forwards between them. Fay’s portraits and abstract works are also counterpointed, continuing this lively exchange. This might all sound quite formal and carefully considered, and indeed the exhibition is both of those things, but it also contains a heartbreaker.

Brian Fay

A Mobile Living Thing

Installation view, dlr Lexicon, Dún Laoghaire

Photo: Lee Welch

Having initially studied in Dublin and London, in 1921 Jellett moved to Paris with her friend Evie Hone and enrolled in the atelier of André Lhote. Under the influence of Lhote, and later of the self-proclaimed founder of Cubism, Albert Gleizes, she developed her own brand of Cubism, first seen in Dublin when she exhibited with the Society of Dublin Painters in 1923. (The influence likely went both ways.) The hostile reviews – George Russell accused her of suffering from artistic malaria – did little to deter her, and her subsequent work and career was important in helping to move Irish artists and audiences beyond parochial concerns. The four Jellett paintings in A Mobile Living Thing were all made in the 1930s. They appeared at something of a juncture in the artist’s practice, as her abstract style was giving way to more figurative influences, especially where religious subjects were concerned. This notion of a pivot or turning point is explored in a direct way in The Ether Series. Based on Jellett’s Abstract Painting 1937, and under the direction of Gleizes’s Cubist technique of the rotation and translation of the picture plane, Fay turned his page incrementally as his composition developed, effectively rotating and repeating a pattern of tiny nodes corresponding to spots of damage on Jellett’s painting, and filling in the remaining area. The result is an array of small white or uncovered areas in an otherwise blackened field. With dark backgrounds hosting constellations of tiny white dots, the drawings are inevitably reminiscent of the night sky (and the heavens are also turning). Like similar drawings by Vija Celmins (also made from other images, rather than direct observation), Fay’s ‘night skies’ are not illusionistic. The build-up of short, closely worked pencil lines keeps your eye on the surface, their overlaps and striations pulling you back from illusory depths. While the starlight they suggest – like the painting to which they respond – comes to us from the past, the play of surface and depth keeps us grounded in the present.

The exhibition title comes from Jellett’s characterisation of the painting process as a ‘mobile living thing’. Fay adapts this idea to the afterlife of the paintings themselves – physical objects subject to the rub of time. Considering that her materials (in this case watercolour and gouache) may have been of poor quality (the spotting on the surface suggests as much), the paintings remain remarkably fresh; their colour, in particular, more vibrant than reproductions indicate. Time’s subtle assault is best made evident by Fay’s watercolour drawing, Rotation and Translation – Entropy – After Abstract Composition 1937 (2019). Mapping the damaged surface, the drawing consists of a cloud of tiny, variously coloured dots, the size, shape, and colour of which correspond to the spotting on the surface of Jellett’s painting. The combination of time, material, and chemical reaction becomes the basis of Fay’s delicate mark making. The same template, or map, is the foundation of The Ether Series, too, where the clouds of tiny, translated forms become pure white areas, expanding and contracting within darkened fields. In the larger series, Fay is effectively drawing emptiness, a kind of antimatter around his undrawn areas. The figurative elements of the drawings appear by omission, a constellation of sparks, to paraphrase Doireann Ní Ghríofa, starring the dark. [2]

Brian Fay

A Mobile Living Thing

Installation view: (left) Rotation and Translation – Entropy – After Abstract Composition 1937, watercolour on paper, 2019; (right) Mainie Jellett, Abstract Composition, gouache on paper, 1937

Photo: Lee Welch

The gallery itself is a long, tunnel-like room, extending from the foyer area of the dlr Lexicon library building. There are no windows along its sides, no architectural details to distract from the matter at hand. The artist has wisely broken up this relentless volume by inserting two half-walls perpendicular to the main ones. Picking up on colours in Jellett’s work, these deep blue and warm rust panels bracket the display at opposite ends, preventing it from feeling too much like a procession. Daylight at the far end of the deep space draws you towards the largest work in the show. Jellett’s small entropy: Rotation and Translation (2021) is a drawing on a grand scale, effectively blowing up the microdots of The Ether Series, and reversing them so they become dark forms on an otherwise white surface. These adjustments seem to shift the view downwards, as though the heavens had vanished to be replaced by a dense archipelago. The drawing is partially framed by a linear oak structure, hugging the top edge, and extending unevenly down both sides. Additional triangular forms elaborate the top-left corner, a kind of tracery alluding to Cubist geometries. While sculpturally persuasive, and effective within the exhibition’s choreography, the actual mark making on this drawing is heavy-handed compared to the delicacy of touch seen elsewhere. Not everything benefits from being bigger.

Contrasting with the relatively minor evidence of ageing on Jellett’s four paintings, photographs of Jellett herself, the background sources of Fay’s drawn portraits, seem more subject to the vagaries of time. In MJ Four Elements (2020), we see Jellett in profile, her abundant hair tied in a bun, her gaze slightly stifled, self-conscious. With the profile split vertically and horizontally, Fay has broken the image into four equal portions, the subject appearing pinned down, like a target. In fact, they are just printouts of a digital image in four sections; the artist decided to retain the fragmentation in his rendering. [3] An important aspect of Fay’s skill as a draughtsman is particularly evident here. The poor quality of his source image (its lack of definition), and its further breakdown through the process of digital printing, becomes his subject as much as the photographed figure. Fay retains his finesse, even when his source material is relatively crude. Paired with the final numbered work from The Ether Series (Rotation and Translation 9), the two drawings seem to regard each other warily.

Brian Fay

A Mobile Living Thing

Installation view: (left) The Ether Series (Rotation and Translation 9) After Abstract Composition 1937, pencil on paper, 2020–21; (right) MJ Four Elements, pencil on paper, 2021

Photo: Lee Welch

Alone on the temporary blue wall, just inside the gallery entrance, a drawing called MJ 16 (2020) introduces the show. Also drawn from an original photograph, the work reveals Jellett’s countenance, framed inside an oval like a cameo brooch. In profile, from the raise of her left shoulder she might be holding a brush, her gaze searching beyond the frame, towards some unknown time in the future. Fay gives equal attention to damage on the surface of the original photograph and to the young figure it portrays. The highlights in the loose weave of Jellett’s hair are of a piece with the filaments of light that indicate scarring on the photographic print. Dark spotting on the surface is made of the same stuff that spots the pupil of her eye. She is sixteen. What age would she be now? The oval shape is positioned low on the page, as though heavy, like a heart. Fay is there for his subject, as a form of communion and redescription. His presence overlaps hers. The rendering of this image is so refined, so overlain with feeling, that it feels like a kind of love.

Brian Fay

A Mobile Living Thing

Installation view, dlr Lexicon, Dún Laoghaire

Photo: Lee Welch

Photographs are passed from hand to hand. Fondly exchanged, photographic portraits are gathered into albums, and sometimes, pressed over hearts. But a photograph is not precious in quite the same way as a painting. A photograph’s vulnerability to time is less physical than metaphysical – especially now, when they are so seldom printed. A painting might improve with age, but people don’t. People diminish, and eventually disappear. Conservators can’t help. Through Fay’s pencil portraits we glimpse the melancholy of photographs, their subject looming from ‘the back of the visible’, to borrow a phrase from John Berger. In The Ether Series, the artist’s approach is more objective, translations coded through material investigations. In attending to things that undermine a work’s integrity, Fay reminds us that integrity is also the acceptance of change. Objects – like us – are real in their vulnerability. A Mobile Living Thing moves between different registers: the figurative and the abstract, the now and then, the him and her of Fay and his subject. Jellett’s insistence is borne out.

John Graham is an artist based in Dublin. He is a lecturer in the Yeats Academy of Arts, Design, and Architecture (YAADA) at IT Sligo.

Notes

[1] Mainie Jellett, ‘An Approach to Painting’, originally published in The Irish Art Handbook (1942). Republished in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, vol. 5: Irish Women’s Writing and Traditions, ed. Angela Bourke et al. (Cork: Cork University Press in association with Field Day, 2002), 1085.

[2] Also exploring time-based enigmas, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s To Star the Dark was published by Dedalus Press in 2021. The line referred to comes from the poem, ‘Brightening’.

[3] From a radio interview with the artist, Arena, broadcast 13 October 2021.