The empty corralling of theory and over-use of jargon that pervades an increasingly marginalised visual art discourse in Ireland is affiliative to the point of being conservative and unwelcoming. This manifests itself in the over-usage of lifeless words that operate sluggishly in the vague but precise-sounding recesses of an increasingly sciencified system of art discourse, and art/art theory education. The words that occupy these rarefied recesses lack amplitude. It is the amplitude of the range of their meaning that give words their life.

In this short essay, my intention is to consider what compassion can do to art criticism, and by extension how visual art might be written about. Here, by compassion I do not mean solely that one recognises the Other and treats this other in a sympathetic way, forgiving all faults and excesses. I mean to take this instinct and consider it in another way. Humane, complex, and relevant criticism in art comes from a place of compassion that is fundamental, and it opens up a number of further levels of interaction between artwork, artist, writer, and reading public.

Compassion in art criticism stems from a rigorous interaction with the artwork or artist you are engaging with – almost to the extent that your life depends on it. This sort of engagement creates a place whereby the critic honestly applies the same intensity of critical engagement to him or herself as he or she has done to the artist/artwork being engaged with. This creates an ever-deepening cycle of questioning and self-questioning, appraisal and self-appraisal, judgement and self-judgement. This instinct and private gesture of shared doubt and appraisal happens as one engages with and writes about the artist/artwork, and after these activities. This also goes toward changing the nature of the gaps between the public gesture of an artwork and the forming of an opinion about the artwork, this opinion being expressed publicly, and in turn the relationship with the reader of this opinion. This cycle of questioning reduces the chances of a critic being dismissive and/or negative – and I mean negative in three senses here: not just an absence of encouragement, or the lack of anything offered in place of a denigration, but also by only recognising as innovative something they recognise for already having once been innovative. From this we get the application of ‘taste’ to artworks, a situation whereby artworks can almost never affect the critic’s taste.

The sort of compassion that I am talking about here creates a situation in the critic’s practice whereby it is as important, or dangerous, to say something critically positive as it is to say something critically negative. The intention is not to create a stultified form of criticism, but quite the opposite. By the critic being as critical of him or herself as he or she is of the artwork or artist being appraised, there emerges a cyclical, fluid sympathy in their thinking, judging, and writing. It involves a measure of the writer’s ability to judge in sympathy with a measure of the artwork being judged. The writer becomes immersed in, and writes from the situation of the artwork, thus offering a history-from-below of it, which over time will contribute to its official history.

When relaying one’s opinion of an artwork, this cycle of judgement and self-judgement should be allowed to extend from what you say into why you say it, and how you say it, i.e. is the language you employ to talk about the artist/artwork compassionate? This engagement with language is done on at least two levels: one, through a meaning you hope to communicate and, two, through the nature of the words you use to relay this potential meaning. Writing about art can be done from the simple to the complex, at word, sentence, paragraph, published text, and oeuvre levels. If you wish to be understood you are writing to the reader’s curiosity. If you feel you ought to be understood, you are writing to the reader’s education. These two situations create different uses of language. I think when one is writing about art, one should be aware of these situations, and question one’s interaction with them.

*

People external to the discourse of art can contribute to the discourse in a meaningful way, thus widening and deepening it, and making it still more complex. It is within this complex, unstable, and growing tissue of art discourse that people can navigate based upon appeals to their curiosity, not solely to their education and tastes. Writing about visual art and discussion about visual art can be done using a language and style sympathetic and invitational to those people who do not discuss or think about visual art on a regular basis, thus making a gesture outward from the discourse, while still not doing a disservice to the complexity of the artwork being discussed. The extraordinary difficulty inherent in attempting this is the responsibility, now, of those within the discourse of art, i.e. the artist, the art-writer, the critic, the editor, the curator, the educator, the student, etc. This should be an ambition in their practices. The belief in and the use of the astounding instability of words is where this effort can begin. A reader, any reader, should be invited to lie on one’s back upon the possibility of a sentence all the while facing outward at a universe of multiplicities suggested by it.

*

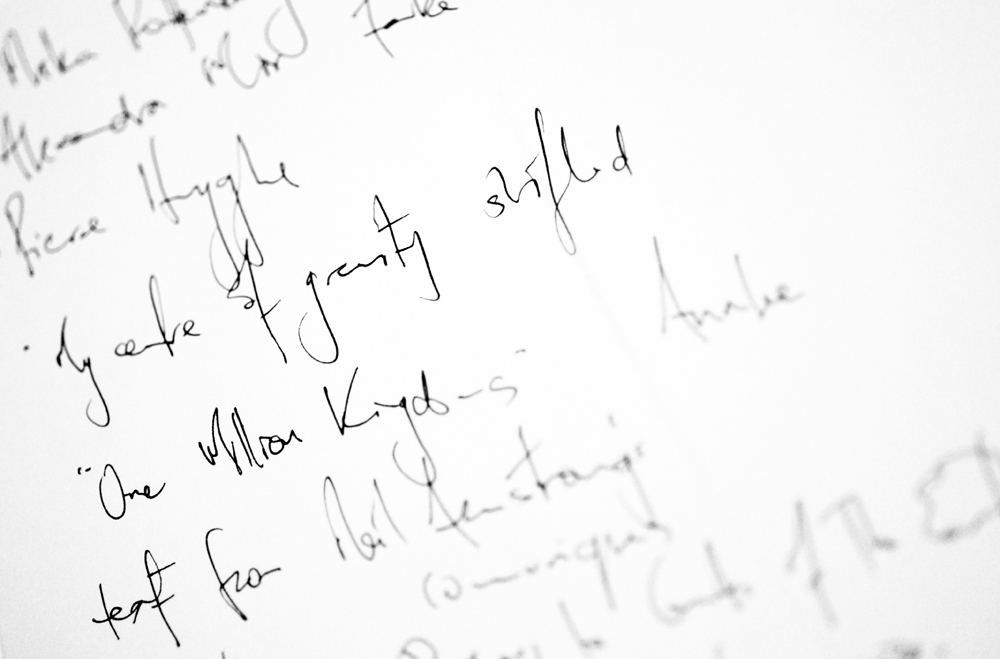

Creating writing and discussion about art in a way that is compassionate will change the manner with which the ideas in it are communicated too. Quantitatively less might be said, but I believe the language that stems from this shift in emphasis will also force the writer/the thinker about art to say something new, and ask new questions that stem not from fear of a need to legitimate the asking of the question. Writing here will cease to be an exercise in the dressing of the absence of thought. This shift in emphasis will trigger a curiosity in oneself as writer, a curiosity in one’s interaction with the world of art, and a curiosity in one’s expression of this interaction. When the articulation of ideas becomes important, these barriers of language will naturally eddy into insignificance. Words here will have moments – like musical notes – of appearance, reverberation and decay, leaving the reader with an experience of a text that is a version of the writer’s ideas only.

*

In most visual art writing in Ireland the affectation of ‘writing’ has been adopted without any of the attendant rigour or artistry or magic. Visual art is ‘covered’ in a brutal pseudo-journalistic way and essayed about in a straightforward manner. And this elucidates a suffocating sub-ordination of the written to the visual that seems to be accepted, perpetuated, and at times lauded. Art can be written about greatly. Art-writing can be something that can be read by, and open up places of interest and perhaps even joy for all – simply through the writing itself. And from this kind of writing we may also be given some other unspeakable clue as to the fascination evoked by the artwork that initially compelled the writer to write about it – thus somehow offering a further unforeseen sense of the artwork, and an unforeseen sense of the relationship of the artwork to the writer.

Adrian Duncan is a writer, artist, and engineer who is currently based in Dublin.

* This is the second part of a two-part essay. The first essay titled A Proposal for Activation in Visual Art Writing was published in the Paper Visual Art Dublin edition and can be read online here. Compassion in art criticism was recently published in our Limerick hard copy edition last August, 2012.