Christopher Mahon’s art practice could be described as sensual, shapeshifting, slippery, chameleonic, elusive, intimate, sociable. On the one hand, he carves fleeting moments into stone: hammering gestures into physical form and inviting us to engage with a material object. On the other, his practice is broad, open-ended, spatial, and performative. Mahon is interested not only in the object, but also how an object might transform when it’s placed in a certain space; how it travelled to that space; where the stone came from, how it was carved, and for how many years it had been carried around in his pocket.

‘I spent years carving different pieces and then carrying them around’, Mahon told me earlier this year, in one of several long phonecalls that informed this essay (full disclosure: I have a personal friendship with the artist, one that has been shaped by conversations such as these). ‘One I showed at the Rijks is from the Theatre of Dionysus, at the foot of the Acropolis, that I then carved. It’s been with me on the beach in Athens, and it came with me to Cairo, to Amsterdam, and then here [Dún Laoghaire]. It’s a beautiful stone in its own right but more importantly it was put in place by the ancient Greeks as a building block for performance.’ Every object has its own secret history, I suggested. ‘Yes, but it’s not going to tell you.’

RGKS Cribs #1: Christopher Mahon (video still)

Commissioned and produced by RGKSKSRG, 2019

Videography by Cian Brennan

This conversation took place in the run-up to Mahon’s RGKS Cribs event in March. Curators Rachael Gilbourne and Kate Strain invited a small ticket-holding audience into Mahon’s Dún Laoghaire home and workspace for an ‘expanded studio visit’ of sorts. The day started on White Rock beach, where Mahon had installed a small sculpture – a pair of eyes carved from stone, peeping out from the rocks – before continuing to the house/studio to gain an insight into his working practices. The space is Mahon’s family home, so is also populated by artworks, projects and unconventional objects made or accumulated by his artistic parents over the years. As well as a snapshot of Mahon’s studio practice, the visit offered a sort of artistic backstory, acknowledging how growing up in this kind of generative, art-making environment has influenced his approach.

It was not my first time visiting the house. I had been there some months previously, after the wedding of two shared friends: a dozen or so of us scooped up illicit red wine from an afterhours grocery shop and poured ourselves into the kitchen to make chat until the small hours. I have a hallucinatory memory of reeling around the garden, all broken fragments, hodge-podge flotsam, trinkets, half-finished sculptures, unruly plants. ‘What’s that on the wall?’ a friend asked the artist’s father, who had joined us in the kitchen for a glass of wine. ‘It’s part of a jet engine’, he replied, and that was that. The experience placed Mahon’s work in a new context, for me.

RGKS Cribs #1: Christopher Mahon (video still)

Commissioned and produced by RGKSKSRG, 2019

Videography by Cian Brennan

The RGKS Cribs event opened up the intimacy of this experience to a slightly wider (but still necessarily limited) group. White Rock beach, where the day began, has had a formative impact on Mahon’s approach to life and art. A devoted sea swimmer, he once staged an exhibition of stone sculptures in the whitewashed changing shelter. He says the beach is where he sources stones for much of his work. It felt like a natural place to begin. Continuing on into the house, guests were treated to a surprise performance by musician Davy Kehoe, giving a haunting rendition of Nina Simone’s ‘You Can Have Him’ – in Mahon’s words, a song about ‘ownership and loss’. Envisioned as part of a series that aims to stimulate insights into how working environments can shape an artist’s practice, a subsequent iteration of RGKS Cribs involved a visit to Vivienne Dick; future artists include Eithne Jordan and Bea McMahon. The event series is a welcome celebration of the artist’s studio at a time when they are under threat. RGKS Cribs proposes a more holistic approach to the presentation of art.

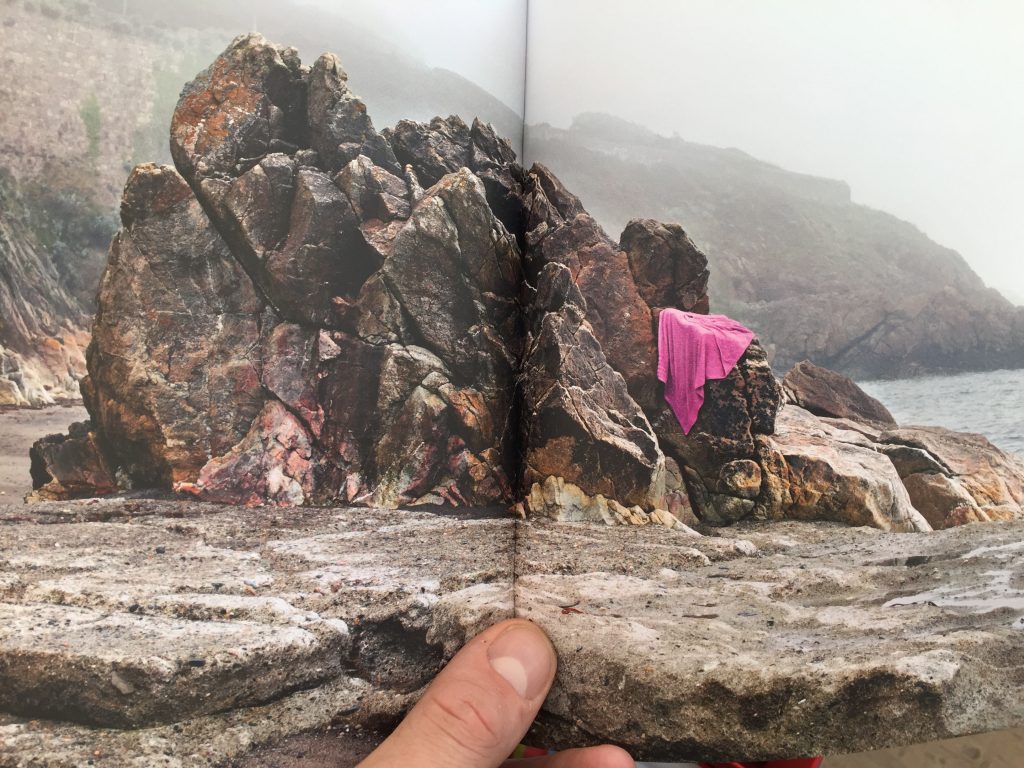

RGKS Cribs #1: Christopher Mahon

Research photograph, showing 8:30 a.m. May (2017) from the series Into the Sea by Gerry Blake (TLP Editions, PhotoIreland, 2018)

In a funny reversal of this process, Mahon’s solo exhibition at Project Arts Centre late last year, Couched, brought his domestic architecture and family history into the gallery. Dimmed lighting created a theatrical environment for an arrangement of objects in the space: a pinkish couch, screen printed with geometric textile patterns and an image of a smashed-up doll, and a louche red rug littered with broken disks of plaster cast sculptures, beaming under the glow of a spotlight. Entering the gallery when it was empty, you had the feeling of having missed out; of walking into a party venue the next day, when all the laughter has drifted away but the detritus remains – and a particular energy lingers.

Much of Mahon’s work involves a subtle shaping of a particular environment in order to allow something unspecified to happen. ‘A couch is such a beautiful thing because it’s as much about the space it proposes’, he told me during the run of Couched. ‘It’s mapping out a space where something might happen, or something did happen. It becomes this kind of theatre.’ Couches are typically private, places for gestures of intimacy and relaxation, for lounging, reclining, reflecting, socialising, kissing. The couch at Project was a dynamic force: throughout the run of the show, objects were perched on it, talks took place on it; it moved around. The idea was for it to be not just a couch, but a forum for other activities to happen.

The couch itself was taken from Mahon’s family home. His father had it made by some set designers he was working with in the late ’80s/early ’90s. For the exhibition, Mahon had it reupholstered, silkscreening the fabric with designs his mother made in art college in the 1970s. When the first print turned out too pristine, he washed it and started to make the colours run and get muddied. To a large extent, Couched responded to the ways in which art objects were integrated into the artist’s home when he was growing up. Artworks were ‘always on top of something, or behind something… one day you’ll clear the table and put something in the middle and it’s highlighted, but then it can go under the couch or behind the piano, and it gets forgotten about. So it’s like this surfacing, appearing and disappearing.’

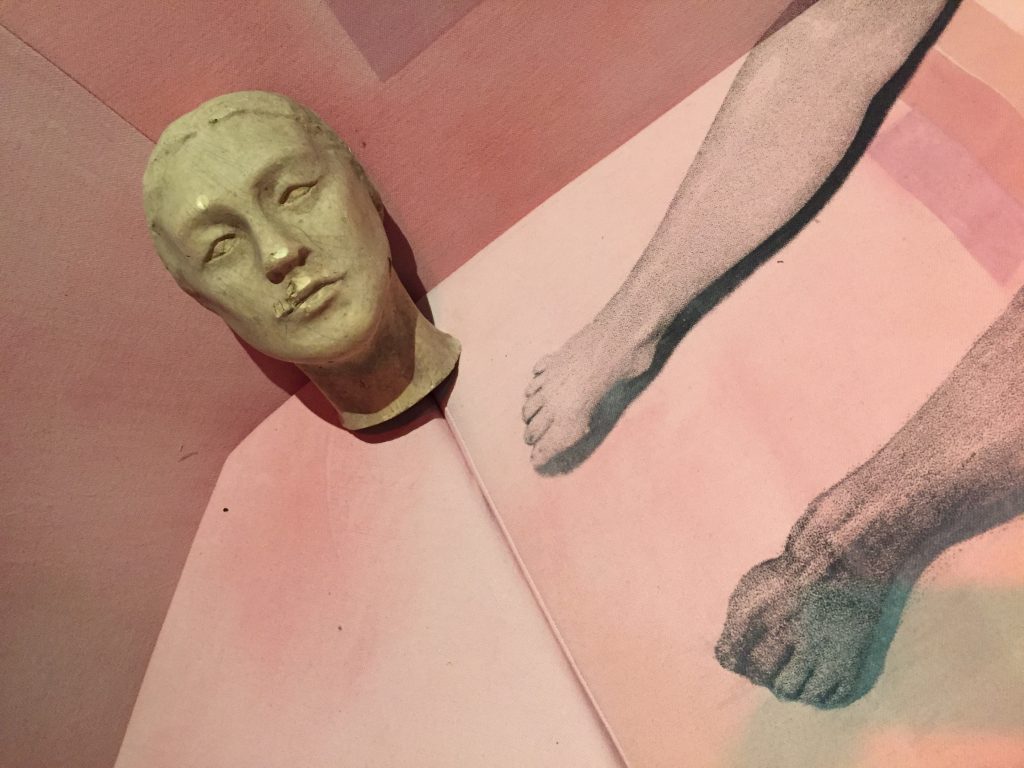

Christopher Mahon

Couched

Project Arts Centre, 4 October–22 December 2018

Photo: Roland Mahon

That broken, doll-like figure silkscreened on the fabric was also a creation of his mother’s. Once a sculpture, it was smashed up at an out-of-hand teenage party some years ago – bits and pieces of it have drifted around the house and garden ever since. Mahon reassembled it, then worked with his father to photograph it. ‘In my parents’ house, with junk everywhere, you’re getting all these fragments of histories and then they all come together and make this kind of incohesive cohesiveness’, Mahon explains. ‘That couch has been in my sitting room all my life. It’s literally been the backdrop to everything. Every sculpture I’ve ever made has ended up sitting on it at some stage.’

This treatment of artworks as banal household objects is a break from the more familiar, white-gloved approach. When artworks are taken out of the market system – when they are stacked up at home, like pots to be washed – their objecthood is restored. A piece of art becomes like any other thing knocking around the house. That couch in the Project show was behaving like a sculpture, but now that the show is over, it has gone back to being a couch again. ‘It’ll all go back to my parents’ house and on the first day there’ll be a wine stain on it’, he said to me during the run of the show. ‘It’s just an instant. That’s all it ever is.’

Mahon posits that his work is ‘never a representation’, more of an action, or a ‘live moment’: ‘something actually has to shift, or be set up in the space’. Digging through his parents’ stuff for the Project show – asking them questions, or asking them to facilitate the making of pieces – became part of the gestational energy that spawned the work. The word ‘unfolding’ comes up a lot in our conversations. An artwork will fold into another artwork, and be used again – in a performance, or in a film, in a sculpture. For instance, a number of his sculptures began as a ‘phrase’ (in choreographic language, a phrase is an assemblage of gestures, like how words make up a sentence), which were then sculpted into stone, ‘like hieroglyphs’. Two of the resulting sculptures from this series were subsequently destroyed with an angle grinder and incorporated into the artwork placed on White Rock beach for RGKS Cribs: ‘I carved it, smashed it, glued it back together again, and then sanded it, carved it again … And I like that, because I think actually, when you start garbling work in on top of itself, using one work inside of another, something of the essence falls back into it or clashes, and I think that’s where it gets interesting.’

Christopher Mahon

Couched

Project Arts Centre, 4 October–22 December 2018

Photo: Lívia Páldi

This fluidity, of objects flowing into one another, typifies Christopher’s approach. There’s also a catharsis in this act of breaking an object down. ‘Smashing something kind of signals a break, a crack through your thinking’, he tells me. ‘It’s a violent act but it can be a loving act.’ Part of stonecarving’s appeal for Christopher derives from this paradox: ‘this ultra-beautiful surface that you get … slick, solid, wholesome’, he says. ‘It’s so seductive, but carving it is so aggressive and shattering. It’s absolute permanence and absolute fragility.’

At the opening of Couched, Christopher had three actors enact a sort of anti-performance: unannounced, and without pomp or ceremony, they walked across the rug, shattering the papery white masks on the floor, and sat themselves down. The effect was of careless visitors nonchalantly damaging the works. Audience members were confused. Were they meant to be there? Was something going to happen? ‘The whole idea was that there was never a round of applause, no beginning or end’, he explains. ‘It’s this weird voyeurism – at some stage, you figure out that they’re sitting staring and everyone’s surfing around, watching them, but everyone’s kind of nervous.’

Christopher Mahon

Couched

Project Arts Centre, 4 October–22 December 2018

Opening night documentation

Photo: Senija Topcic

The performers were cast by Momentum Acting Studio in Dublin, which teaches the Meisner technique – a method that explores ‘the dynamic that you can portray without words’. Rather than the old-fashioned theatrical techniques of voice projection and diction, the Meisner technique creates scenarios or uses word exercises to bring about a shift in atmosphere. Repeating a set phrase, for instance, until ‘you begin to hear what’s behind what’s being said. The emotions start to bubble.’ For Couched, the three actors set up a scenario and played it out ahead of the performance – and then carried that tension into the gallery space, so that even though the performance was non-speaking, it would still communicate a particular energy. ‘Everyone knows that feeling – when you walk in a room and you’re like, something happened’, Christopher elaborates. ‘You can’t hide behind it.’

Next on the horizon for Mahon is a group show, Suffis-toi d’un buis, at Ménagerie de Verre in Paris, normally a dance space. For this exhibition, Mahon will be producing new work in collaboration with Morgan Courtois, an artist with whom he set up Pub32 cabaret in Amsterdam, and Lyse Seguin, who taught him choreography at the Sorbonne. Morgan will cast a collection of glass vases in porcelain; Mahon is choreographing a work for Lyse to perform at the opening, and making a new sculptural work. The latter will begin in a workshop in Cairo, then travel to Amsterdam (where the artist is currently on residency at the Rijksakademie) to be lacquered by a specialist before being driven to Paris. ‘That now becomes the choreography’, he reflects. ‘It’s not just about the show, it’s about how you produce it: where you travel to get it, how you collect the stone, the journey it goes on.’

I would add to this the orbit of viewers around it, to paraphrase a Robert Frost poem, recited by Mahon from memory during one of our phone calls: ‘We dance round in a ring and suppose / But the Secret sits in the middle and knows’. For me, the afterlife of an exhibition includes those who come to see it, and the places they come from; the conversations that take place or introductions that are made on the night of an opening; the individual worldviews that are shaped by the run of a show; the moments of resonance that are sparked – not only by looking at artworks, but discussing them afterwards in the pub. These social encounters are a fundamental and formative part of the process for many visual arts practitioners. With its interdisciplinary and often collaborative nature, Mahon’s practice both responds to and enhances this essential sociability of the artworld, making a case for its generative potential.

There is still room for the private, however; for relationships to blossom directly with artworks. As Mahon points out, ‘if you see a great work, you come away thinking that you understood it the best, or you saw something in it just for you. It creates a moment of intense privacy that I think is really, really, really beautiful.’

Rosa Abbott is a writer and curator based in London.