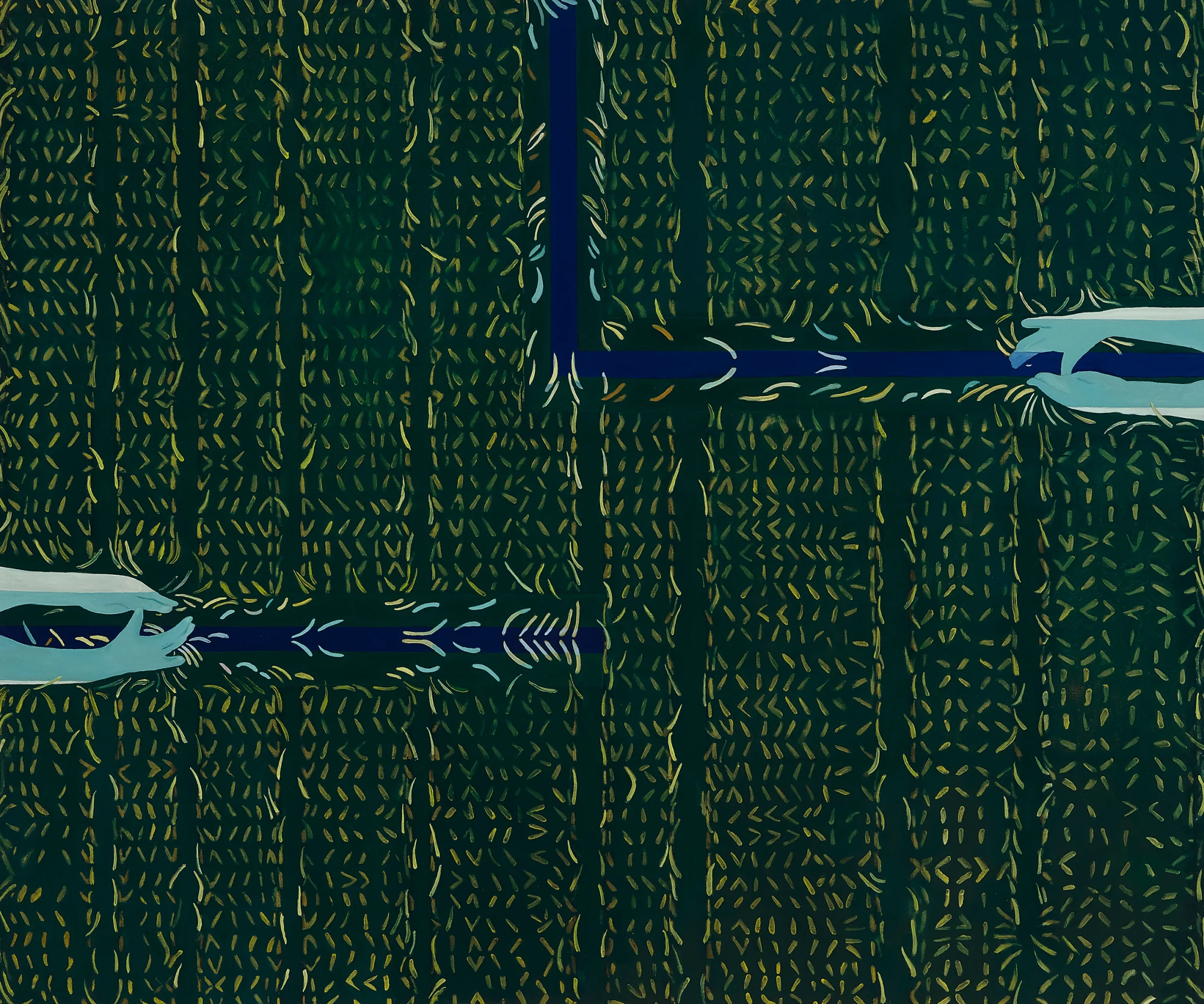

Sonia Shiel’s 2019 painting My Understanding, is a good place to pause before contemplating these new works. We might figure it for a self-portrait of sorts, conjuring a moment of imaginative divination. We might. Our innate human need to know what is going on, will not be stopped at art’s emotionally saturated facades. Such immediate, experiential enjoyment leaves us feeling vulnerable, perhaps even a little duped. We find it difficult to appreciate artifice for its own tantalising sake. On the whole, an artist will not labour under the expectation of a hypothetical viewer, and why would they? It is difficult enough to bring thoughts from crucible to cast with gratifying fidelity, both emotional and visual.

Sonia Shiel

My Understanding, 2019

Oil on canvas, 40 × 50 cm

Courtesy of the Kevin Kavanagh Gallery

Those in the art world must regularly dwell over the way information is handled and manipulated within it. About knowing the extent to which it should be communicated and the nature in which it should be told; about obscuration; about the pressure of a system that often demands explanation. When we look at art, that which moves us might be some part of ourselves subliminally reflected back and it is possible that in the wrong hands information has the ability to act as a block to this. So – barring titles – can certain types of information be antithetical to the experience of art? The thought nags me, and I will usually hold off reading accompanying texts until after viewing an exhibition. Artistic creation, though inspired by the world, needs to make reality dissolve away around its own formation. The facts of success or failure are real-world matters, but creative expression is a succession of perpetual, unresolved attempts, impossible to quantify, existing as they will in the alternative realities of its audience.

Ideally, the artist gives as much as they wish to: about a particular piece, a series, a project, or an exhibition. At one extreme might be an exhibition called New Work, full of Untitled pieces, with just a few biographical details on the gallery handout. Towards the other, titles might offer anything from directions to coordinates, while artists’ texts can veer towards the cartographic. The exhibition system often demands an array of didactic material from even the most reticent artists, both written and verbal. It is a ponderous balance. Particular background information might unlock enjoyment for certain works, but there can also be disappointment in knowledge and sometimes nothing equals more than something. Ideally, an artist would expand into textual embellishment only where artistically gratifying and the extent to which they do this naturally is the right amount, whether or not it sweetens or sours the enjoyment of any particular viewer.

The exhibition text here is a short correspondence: a message to the artist from Glucksman curator Chris Clarke, and the reply. He notes that Shiel had previously told him to feel neither pressured into being ‘specific or definitive’, nor to feel he had to ‘explain the work’. Interestingly and unusually, Shiel’s response (and second half of the text) outlines each painting’s scenario in a way that flits between quotidian detail and detached speculation. The latter exists out of the former and is the more enchanting, as it shows Shiel as a curious traveller rather than the omniscient architect in the world of her own making:

When we remember

Here on a tartan blanket three pairs of legs picnic. A glass on the top left corner spills over the whole scene, blurring the tartan’s rigid linear design and cascading beyond its measure. When we remember it is never clear. It is unreliably good or bad, true or false. Here the components of tartan are all there but in disarray. They fuse in a kind of collective happy or a collective weep. Only the colour stays the same … a hue of yellow-pink, the colour of nostalgia, summer holidays, childhood and wibbly-wobbly wonders … long gone but memories of yum.

Language is an important part of Shiel’s work and it is here that the crux of this exhibition is: that in knowing the corporeal genesis of an image does not betray an artwork’s power, or diminish its ability to convey a rich psycho-narrative, with the artist by your side.

Shiel’s video, painting, and sculpture (the last two usually blending into one another) between about 2006 and 2016 had a distinctive, wry humour. Even where it was not overt, this playfulness permeated almost all of her work, often with titling playing an important role. Her very style was enough to prompt a Pavlovian response of amusement in me. It didn’t matter whether or not I fully understood the occasionally oblique references. This humour is still there, but its visual timbre has changed. More recently, and particularly in The Dangers of Happy, that palpable yet mysterious energy has shifted to a more abstract tenderness and melancholy – a visual checklist of foggy notions. Each title here begins with When we …, suggesting scenarios more than scenes, though the reference to drama could be useful.

Where previously Shiel nestled her compositions within bordering devices such as painted frames or theatrical proscenia, these paintings do not feel constrained by borders and every delineation could be reckoned as continuing beyond where Shiel has applied the scalpel to a larger imagining, however hypnogogic. There is the sense of a continuum in these works. The kind of distortions that remould memory when we think of when we did something. The titles are completed in sanguine moods, but ones that are pregnant with the possibility of failure. If the past year and a half has imbued us with nothing else, it is the impetus to live our lives knowing how fragile happy is.