Sterile Environment, a recent group show that took place at Catalyst Arts, explores Belfast’s changing physiognomy and includes work by Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell, Andrew Dodds, Aideen Doran, Eoin McGinn, Michael Pinsky, Keith Winter, and Forum for Alternative Belfast.

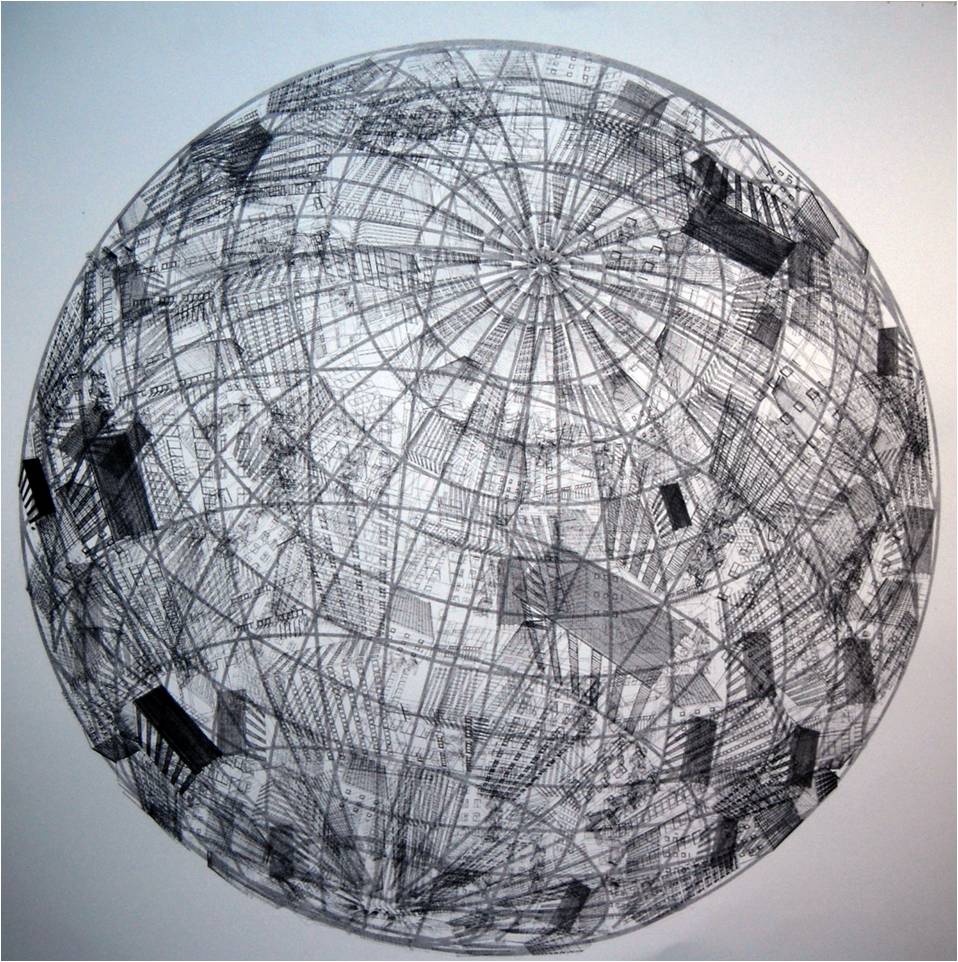

On the outside wall of Catalyst Arts, Eoin McGinn’s stencil piece reads in black, capital letters: “Dreamed of Places.” Inside, McGinn’s Urbanisation (2011) is a detailed screenprint depicting the built environment from various angles and overlapping perspectives. The drawings, based on Belfast architecture, resemble technical drawings, however, instead of neatly arranged plans they are disorderly – a chaotic representation contained within a sphere. Space and the objects within are not static, or clearly defined they are instead a representation of the the layers of structure and meaning that exist. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty says of the relationship between the individual and objects: “The things of the world are not simply neutral objects which stand before us for our contemplation. Each one of them symbolises or recalls a particular way of behaving, provoking in us reactions which are either favourable or unfavourable.”[i] McGinn’s work also brings forth questions of city planning – how the built or unbuilt environments will affect the future. Just as the graffiti on the outside wall of Catalyst will soon disappear, so too will these dreamy, utopian ideals of yesterday that will never become manifest.

Eoin McGinn: Urbanisation, 2010, screenprint; image courtesy the artist and Catalyst Arts.

Eoin McGinn: Urbanisation, 2010, screenprint; image courtesy the artist and Catalyst Arts.

Beside McGinn’s piece is Andrew Dodds’s Within spitting distance (2011), a large black-and-white print hung on the wall. The archival image (c. 1980) was photographed in Cornmarket, an area in Belfast that was a meeting point for so called counter-culture youths during the 1970s and 80s. Punkish looking youths sit on wall dressed in tight jeans and boots. Cornmarket has now been given an extensive makeover – known as Victoria Square, it is a gleaming shopping centre with a massive glass dome and over fifty retail stores that opened in 2008. As a result of this development, these former gathering places have been replaced by Top Shop, Miss Selfridge, and Boots. As Dodds’s piece points out, space and time temporal. Such globalised models and places for development take no account of previously existing structures or cultural areas – either official or informal. This candid photograph, enlarged and placed on a gallery wall takes on an unexpected significance. It becomes active a second time as a reminder of the palimpsest of historical moments which have existed in a single place and have long since disappeared.

Aideen Doran’s video Homes for today and tomorrow (Belfast) is subtle and compelling. The video, projected on a timber construction that is held in place by two burlap sacks, shows archive footage of the now demolished Divis Flats complex in Belfast that were built in the Brutalist-style between 1968-1972. Footage taken from UTV shows close-ups of windows with coloured curtains, children playing, images of the Divis tower and apartment complex itself. The garish and bright images seem almost futuristic, like clips from a sci-fi film from the 60s. The video piece seems to illustrate a shifting between the past and the future as the slow, rocking forward and back between images like a suspension in time.

Aideen Doran: Homes for today and tomorrow, installation view, video, timber frame; image held here.

Aideen Doran: Homes for today and tomorrow, installation view, video, timber frame; image held here.

The 1956 exhibition This is tomorrow was a multidisciplinary collaboration of artists, architects, musicians, and graphic designers that took place at the Whitechapel Art Gallery London. The exhibition revealed and reflected the underlying motivation and ethos of Brutalism – what architectural critic Reyner Banham’s metaphorical ‘garden shed’ view described as a place where the shed, the distant past, and the future merged.[ii] In this show, Richard Hamilton’s wonderfully titled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing, clearly elucidated the Brutalist domestic image. Hamilton’s collage depicted a muscle man holding a giant lollipop with the word ‘POP’ across it. It is this mix of pop art, architecture and consumerism that can be mapped onto the Divis apartment.

The Divis tower is a marker in Belfast’s history. Instead of providing homes for the future, it was a temporary container for the old way the new ways of living, just as Doran’s film-object offers an extended space of representation but only for the duration of the exhibition. In effect, the idea of the home, a space that endures, is removed and instead this development seems to mark an unsuccessful solution to housing problems – a degenerate and failed home of the future.

Keith Winter’s impressive and well constructed Balls2thewalls is a large floor-to-ceiling structure made of timber, glass, tarpaulin, and cardboard. The timber frame is divided into two parts: the bottom half made of a glass window and sheets of plastic, while the top half is made of cardboard shaped into geometric patterns. The glass reflection creates an illusionary extension of the gallery space while the shattered glass, seemingly broken by the small geometric object and folded triangular shapes made of cardboard on the ground, seem to further illustrate the tenuous nature of these spaces and objects. At the back of the structure, one can walk under the solid frame made of old timber. Inside, the distinction between old and new is apparent. From this angle, the cardboard shows markings of paint and tape on the surface. Two delicate lines of light trace this geometric surface and there is a smell of timber. Winter’s use of materials – cardboard, broken glass, plastic – undermines the strength and weight of the structure deeming it weak and temporary.

I recently read Bruno Schultz’s The Street of Crocodiles, a curious collection of stories that talks, broadly speaking, of memory and decay. In one particular story titled “Treatise on Tailor’s Dummies,” the narrator’s father describes old apartments as forgotten rooms as those which “close in on themselves, become overgrown with bricks, and, lost once and for all to our memory, forfeit their only claim to existence.”[iii] Overlooked for so long, these rooms merge with the structure and the walls, reduced only to lines and cracks. In Winter’s structure we are left with the artificial and tenuous nature of our surroundings. It does not offer a singular memory or history but instead reveals a correspondence or a synthesis between people and place, where all time merges in the contours of design and material.

Keith Winter: Balls2thewalls, timber, tarpaulin, glass, cardboard, installation shot, 2011; image courtesy the artist.

Keith Winter: Balls2thewalls, timber, tarpaulin, glass, cardboard, installation shot, 2011; image courtesy the artist.

Beside Winter’s Balls2thewalls is Michael Pinsky’s video The endless high street, version 1: Pret-a-Manger (2011) which takes into account the high street as an embodiment of an homogenised society – a cliché of shops and restaurants; a safe and reliable place with no surprises. In the video, Pret-a-Manger, a market-style fast food shop usually located on shopping streets across the UK, becomes a backdrop to city living with a soundtrack of passing traffic. The sign remains throughout the eleven minutes while the location continually changes. In a way, it is a moving picture that doesn’t go anywhere.

Forum for Alternative Belfast is a not-for-profit organisation which campaigns for a better and more equitable built environment. Sterile Belfast (2011) is a video of mapping studies, a visual comparison of the past and the present. This slideshow of maps and facts demonstrates the unbuilding of Belfast over the last few decades. In 1939 for example, there were 470,000 people living in Belfast. In 2010 there were only 270,000. Such a decline in population has led to city centre areas being decimated by road infrastructure, low density housing redevelopment and the proliferation of car parks. [iv] As seen in Dodds’s archival image Within spitting distance, historical and cultural areas are disappearing, now home to shops and businesses.

Builder bowling offers a playful take on the disappearance of buildings in Belfast. Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell’s interactive installation consists of hard hats, high-vis jackets and gloves, and a homemade bowling alley to be used by visitors to the gallery. A tacky, badly constructed sign over the pins reads: Exciting Opportunities for Redevelopment. The plaster-cast pins below are modeled on old buildings due for redevelopment around Belfast, and the accompanying how-to video explains the rules of the game.

Catalyst Arts lends itself well to the exhibition with high, industrial ceilings, exposed pipes and rough edges. This place could well be a site for redevelopment. Sterile environment questions and draws attention to recent urban redevelopments that have significantly altered the physical nature of Belfast. Its history, concealed beneath layers of brick and concrete and timber, is like an architectural membrane that has been peeled away, healed and scarred over time.

Niamh Dunphy lives and works in Dublin.

_____________________________________________________________________

[i] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “The World of Perception,” Routledge, p.48.

[ii] Kenneth Frompton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, Thames and Hudson, Fourth Edition, 2000, p 265.

[iii] Bruno Shultz, The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories, Penguin, 2008, p.38

[iv] Forum for Alternative Belfast website: www.forumbelfast.org