In February 1631 the poet and preacher John Donne ascended the pulpit for a final time. He spoke about mortality. Weak and emaciated from the disease that would soon kill him, he offered his congregation a living example of impending death. A few days later, he posed, clad in his winding sheet, on a wooden structure fashioned as an urn. Modeling for his own effigy, the poet stood upright, facing east, in the attitude of a man who might live forever. Donne’s funerary sculpture, based on the likeness this staging produced, occupies a niche in St. Paul’s cathedral in London. Isabel Nolan has based a body of work on this curious object, and most particularly, on the stone figure’s bent knees. Are the bent knees a sign of infirmity and weakening resolve, or are they, in a flexing before lift-off, a sign of vitality and belief? An integral element of the show at the Kerlin Gallery, a text by the artist describes her ‘peculiar affinity’ for Donne’s memorial and speculates about its effect. Her imagination seems triggered by how the body (exemplified in the idiosyncratic carving) might speak more subtly than the intellect. The standing figure, she concludes, discloses both faith and doubt – his relaxed countenance, his worried knees – in an expression of the seemingly paradoxical but ‘vital beauty of weakness’.

Isabel Nolan

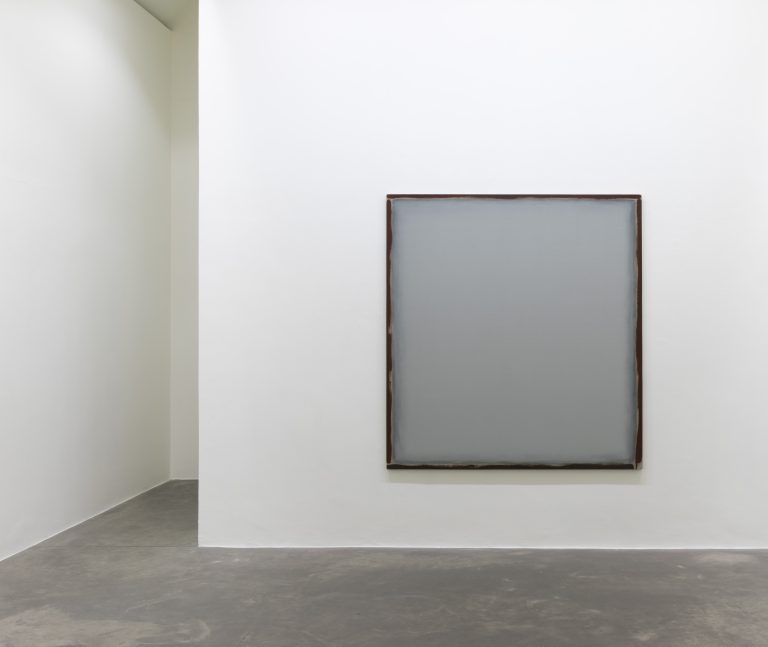

For ever and ever, and infinite and super infinite for evers

2015

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

A parade of unruly, polychromatic flags trail to the floor from bent white poles. Perpendicular to the gallery’s white walls, they encroach on the space from both of its longer sides, their disheveled vestments providing an irregular guard of honour for the gallery visitor. Each flag is made from several sheets of dyed cotton, ranging from colour-drenched reds, to ephemeral evaporations of grey and green. One side of Fresh disorder diminishing energy is blood red bleeding into pale violet, topped with an asymmetrical bib of pink. On the other side a crimson wash gradually leeches into white. The drooping forms vary in their configurations too. The most open of the group, The thrall of gentle derangement feels almost figurative, its parts flopping down and crossing over each other, like limbs dangling at their ease.

In their loose assembly the flags rely on simple steel pegs to hold separate elements in place. In bands blurring across the expanse of each sheet, the colours seem provisional too, as though arrested against gravity, on the ebb of vertical tides. In shades of pink, grey, white, and pale brown, Hungry and Thirsty. Sorry and Angry. A flag for John Donne is the only one carrying an image. Screen-printed in black ink, the shrouded poet appears to be dead, or dreaming. These languid banners – their indolent slouch – seem emblematic of weakness, of quests forlorn or given up. Alternatively, they might be ensigns of humility, their poles bending towards the viewer, in the attitude of a humble bow.

Isabel Nolan

Bent Knees are a Give

2015

Installation view

Courtesy of the Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Nolan’s art is idiosyncratic, but it also exists in a carefully articulated nexus of reference and allusion. Ideas from literature, astronomy, and philosophy combined in her previous Dublin exhibition, The weakened eye of day (IMMA, 2014). Though dealing with light as a metaphor, that show felt oddly opaque, as if the gallery’s small rooms were insufficient to contain the artist’s larger ambition. She has made a more successful concentration here, perhaps benefiting from a quirkier, more singular focus.

When John Donne writes, ‘By these his thorns give me his other crown’, he is identifying suffering with hope. Humans invent ways of dealing with change, among them the inventions that accommodate death. Uniquely aware of our fate, we negotiate our path by harnessing other faiths. These large themes are addressed subtly in Nolan’s show, through her textual meditations on Donne’s ambiguous statue, and in the agile inventiveness her objects reveal.

Sitting squarely in the middle of the floor, a blocky yellow lion raises a wounded polystyrene paw, pierced through with a golden thorn. Elsewhere, the drawing Jesus (after Bellini) torso, depicts the figure as a dead weight, a body pierced and carefully deposited. Another oil pastel drawing, Lucretia, is clearly based on Rembrandt’s painting of the same name. Blood pours from a wound in Lucretia’s side and down her white shift. Her left hand reaches for a chord – too late to summon help – while in her right she holds the fatal knife. Like John Donne, in his way, Rembrandt’s Lucretia remains standing after death, held upright in perpetuity as an image. The effect here is, however, more elegiac than dramatic. Cruel piercings and mortal wounds are softened by distance, and by art. They are depictions of other depictions, and the touch of the oil pastel is in league with the touch it depicts.

Isabel Nolan

Lucretia

2015

Oil pastel and pencil on paper

Courtesy of the Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Two colour photographs (archival pigment prints) show details of the poet’s cream and amber shrine and, though beautiful, could exist for their titles alone. I am wonderfully and fearfully made shows the urn that supports the standing figure, while For ever and ever, and infinite and super infinite for evers frames the figure’s legs, and the anatomical curiosity that has been causing all of the fuss.

In the midst of this melancholy pageant the yellow lion continues to sit. In the biblical story Saint Jerome removes the thorn and domesticates the wild creature. The animal is put in service of the man. In Nolan’s oeuvre, animals – like the dogs and donkeys seen elsewhere in her work – seem to represent humility, a kind of grace. The clunky lion, with his jaundiced, cartoonish demeanour, is neither beast of burden nor king. He is suspended, instead, in his vulnerability and trust – his vital beauty – endlessly offering an injured paw.

John Graham is an artist based in Dublin.