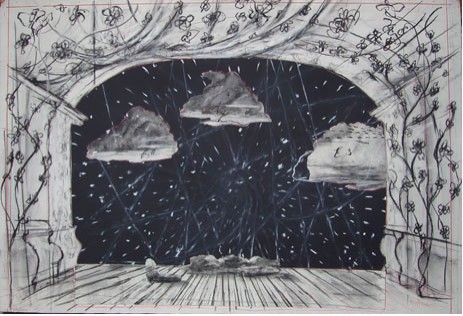

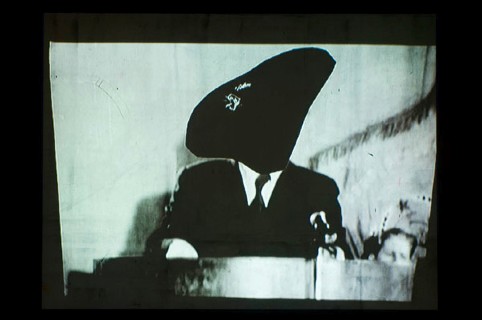

William Kentridge, Drawing for the opera The Magic Flute

2004–5

Charcoal, pastel, and colored pencil on paper

47 1/4×63 in. (120 x 160 cm)

Collection of the artist

courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New Yor

© 2008 William Kentridge

photo: John Hodgkiss

Image courtesy the artist, MoMA.

Five Themes, recently shown in the Jeu de Paume, brings together some forty works by William Kentridge. The show was centred around the themes of – Ubu and the Procession (Occasional and Residual Hope), Soho and Felix (Thick Time), Artist in the Studio (Parcours d’Atelier), The Magic Flute (Sarastro and the Master’s Voice), and The Nose (Learning from the Absurd). The works were displayed over five rooms with a cinema in the basement of the museum. The room dedicated to drawing was the only room not lit by a sequence of projected light. Here, we encounter an evolving series of characters, myths and legends that are magical and exist as autonomous storytellers. In the work, Kentridge describes the truth that lies between the individual and history. At their core is the loss of equity between the event, recollection and discourse. There is a definitive authorship to Kentridge’s work, the artist and his drawings are impossibly one. I will focus on three works which seem to most appropriately address the concerns of Kentridge’s Five Themes.

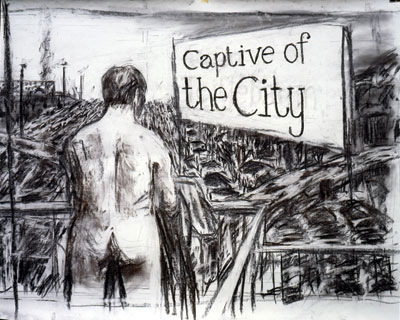

William Kentridge: Image from Johannesburg

2nd Greatest City after Paris,1989

film, 8 mins

Image courtesy of the artist.

While his work is rooted in drawing, it is also concerned with the moving image – filmic history is firmly part of his milieu. It is fitting to see this retrospective in Paris, as in many respects, George Méliès is a clear reference point. Kentridge, like Méliès is the conjurer evoking and effecting reality. Paris, the city of light, plays its part as a centre of visual wisdom. The two characters central to the film Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (Captive of the City) (1989) are Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitlebaum. In a sense, these characters are like metaphors for Johannesburg; one is an industrialist, an employer, and an initiator while the other is a dreamer, a poet and a watcher. Throughout, we see Soho’s face and often only Felix’s back. Both characters bear a close physical resemblance to the artist himself. The film seems to assert, remember and retell the atrocities of apartheid as an integral part of the city’s identity. The title itself emphasizes the periphery and the great distance between the two cities in experience and history. The metamorphosis of the animated drawings are reflective of the nature of the city itself. In effect, the city makes anamorphic the realm of political reality.

Kentridge’s artistic identity is wrapped in his experience of political conflict. Acting as an interpreter, he attempts to fathom the apartheid’s policies of segregation and discrimination, while also acknowledging his own background as a white, Jewish South African. Characters which vary from Capitalist to Spiritualist, navigate the boundaries of an undone world. Like Joyce’s Stephen Daedalus, they seem to proclaim: “ Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience.” [1] Identity is no longer static, but the embodiment of different tangents of history.

Mozart’s The Magic Flute that premiered in 1791, and Dmitri Shostakovich’s 1930 opera The Nose are both tales of hierarchy. In the case of The Magic Flute, the High Priest Sarastro guides the hero to wisdom. Knowledge is linked with the unwavering authority and monopoly of the rational in Enlightenment thought. Similarly, Kentridge’s Black Box/Chambre Noire (2005) engages with such themes through a combination of a video projection and a miniature model theatre. Kentridge considers the black box in different ways: as an optical toy, a precursor to cinema, and as a device used to record information in the event of an airplane crash. [2] These works are preparatory for Kentridge’s direction of the opera in 2005 first shown in the Royal Opera house in Belgium, and function as a mechanized opera in miniature. The projection in Black Box refers to the German colonization of Namibia, and the massacre of the Herero people by the Germans in 1907. Cardboard cut-outs, charcoal drawn curtains controlled by pulleys and levers are accompanied by archival film footage of rhino hunting. This acts as a reminder of the violence inflicted upon all aspects of the African continent in the provision of a Western status quo. The stage set, originating from a culture of spectacular optical entertainment becomes haunted by the ghosts of troubled lands.

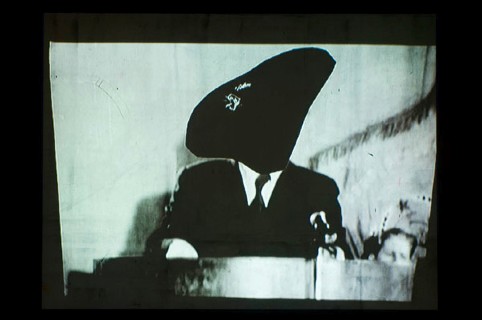

William Kentridge: Commissariat for Enlightenment (still)

from the installation I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008

Eight-channel video projection, DVCAM and HDV transferred to video, 6:01 min.

Collection of the artist; © 2008 William Kentridge

photo: John Hodgkiss

Image courtesy the artist, MoMA.

In the staging of a work that takes its lead from Shostakovich’s The Nose and Nikolai Gogol’s short story of the same name, Kentridge questions the logics of power and status. In Gogol’s story, a bureaucrat’s nose goes missing. Upon finding it, he discovers that it has attained a higher rank than him. The absurdity of hierarchical bureaucracy and the effects of a status on the individual in both public and private are highlighted. Kentridge plays on this folly in a series of work examining the subject and character of The Nose, in an amalgamation of multiscreen projections the nose holds power and topples precariously from its heady heights. He can not reconcile his place in society. In a similar way, the subject of the film Prayers of Apology is the transcript of a Russian operative Nikolai Bukharin, accused of being a double agent, is being interrogated by the Central Committee in 1937. In the transcripts Bukharin states: “ No one believes in human feelings anymore.”[3] This is met only by laughter from the Committee.

These lost histories that Kentridge seeks to hold in check, are revealed through mirrors, theatres and silhouettes.

Kitty Rogers is a Dublin-based visual artist.

__________________________________

[1] James Joyce. Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man. Penguin 1965. p.276.

[2] http://www.e-flux.com/shows/view/2417

[3] William Kentridge. Mark Rosenthal (ed). Five ThemesSan Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Norton Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press. 2009. p.61.