The monumental can be dwarfed by a good laugh, a good joke, or better still with deadpan humour. Brian Duggan’s work in the past often resulted in bemused questions from its audiences of why, and to what purpose? In Door (2005), last seen in the 2007 Irish Museum of Modern Art show (I’m Always Touched) By Your Presence, Dear -, Duggan j-walked a ruined doorway in a video upside down, a rather weather beaten old wall, perhaps an entrance to a vestry of some old monastery: a ruin with a prestigious past. While Duggan’s work has always battled with the immediate environment it has taken place in, the sense remained that the performances took place only out a sense of fondness. Or rather, out of a wish to render the viewer acutely aware of not only Duggan’s finite physical capabilities, but also that of the world that they too inhabit. We’ve all climbed a tree or a wall as children, and with joy; it is possible to see the why and the to what purpose of Duggan’s work as a direct relative of this joy.

Brian Duggan: Half a Half size wall of death

5395 diam by 3768 high

2009

Image courtesy the artist.

Like the ruined doorway lintel Duggan so strenuously compressed himself and the viewer into in Door, the Hugh Lane Gallery is exposed to his game of the impossible, of daring and precariousness. With Step Inside Now Step Inside, there is both a continuation of Duggan’s work and a departure. There is no video for one, and there is no figure, no man in a jump suit as in During the Meanwhile, 2005, or the blindfolded perambulator in A Long Walk Off a Short Pier (Blindfolded), 2008. In fact, what Duggan seems to be doing is paying homage to those entertainers who are closer to circus artists than to performance artists, who could be inferred as being kindred souls for the artist. This is the great spectacle, where the ludic and the technological are fused; in the Hugh Lane the show goes on out of sight, somewhere between the viewer and the gallery wall, hidden from view by the floor to ceiling wooden sculpture Duggan has created, a sound piece letting vent to the pent up excitement of revving motorbikes and a compère setting the occasion over a tannoy.

Brian Duggan: Half a Half size Wall of Death, detail

5395 diametre by 3768 high

2009

Image courtesy the artist.

Taking on the space of Gallery Eight in the Hugh Lane, Duggan built himself his own wall of death, Half a Half Size Wall of Death, referring perhaps as much to the formidable walls of the old Georgian building as much to his own sculpture. One instantly follows this arced wall of wood with its echoes of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, as if the traction of its curve alone carries you to the vanishing point between this celebration of daring-do and the wall of Duggan’s chosen playground this time around – the venerable old art institution. Unlike Pink Floyd who built their wall up, only to knock it down, this wallification suggests more the stage of Eugene Ionesco, with the complete assembling, during the course of his play Les Chaises, of a line of chairs with their backs to the audience. The power of the wall in the art space stems from the negative performance it immediately creates for the viewer: a left turn, a right turn, the effect of the wall of death transplanted from the big top to the art space is the formation of an event of entertainment frozen in time, placed triumphantly in front of another wall of death – that of the museum.

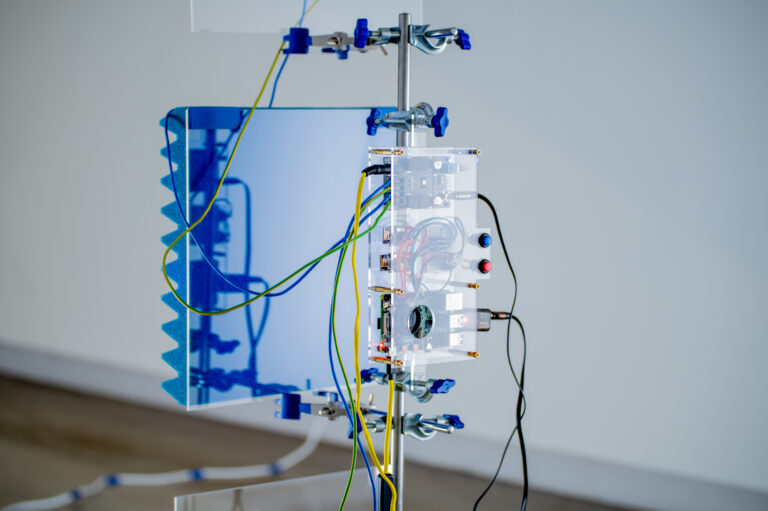

Brian Duggan: Blue Wall of Death

neon and perspex

2009

Image courtesy the artist.

Like the theatre of the absurd, the work of Duggan often feels like a body of art struggling to remain upbeat, or at the very least deadpan, whilst circling around the void, taking pleasure in the sheer difficulty of living and finding an art to circumnavigate these difficulties. Or indeed, just making them up: imposing difficulties, like any restraint in much formalist art, looking for aides in the creation of an artwork. But are there more difficulties in the world than ways of showing them? Duggan’s work suggesting here that there are not: if the tradition of the absurd believed that meaning was what is lacking in the world, hence all the difficulties of life and the ‘entertainment’ built up around exposing them, Duggan’s recreation of his wall of death within the walls of the Hugh Lane, so full itself of ‘dead old men,’ point towards the fact that what are missing are the signs, the artworks. The works made of neon lights and Perspex glass, in bright magenta and green, delineating mini walls of death, reflect the space back at the viewer suggesting that the impossible is a fact for everyone, and not just the brave entertainers and their games of daring-do. Everyone including, it must be said, the artist whose work brings them into contact with the walls of venerable ruins with prestigious pasts.

John Holten