Retrospective is a big word for artists – implying a career that spans decades, perhaps encompassing pivotal life events, plot twists, and artistic breakthroughs along the way. But not all artists are afforded such luxuries of time. Born in 1962 in Lahore, Hamad Butt graduated from Goldsmiths in 1990, presenting his first major installation as part of his degree show that year. Just four years later, he died from complications related to AIDS, aged thirty-two. What we get in the accelerated, distilled retrospective of his work at IMMA, then, is just four years of his sculptural output, bolstered by earlier painting, works on paper, and supplementary archival objects that trace the artist’s development. Rather than charting the slow simmer of artistic development, we are offered a potent cocktail of work: a chorus of tightly realised, ambitious, and powerful sculptures, and a clarion call in the face of crisis.

Housed over the three levels of IMMA’s Garden Galleries, the exhibition is ushered into a tripartite structure. We begin on the ground floor with Transmission (1990), first presented as part of the aforementioned graduation show, serving as a sort of manifesto for the artist – his first ‘active’ response to the AIDS crisis and a radical departure from his previous work. In a Klein-blue-painted room stands a wooden notice board of the kind you might find in unrefurbished community centres, churches, city halls; varnished wood, glass, gold lettering spelling out ‘Transmission’. At first, the word conjures to my mind televangelists – transmissions of sermons, broadcasts, or information; then of course transmission of illness. Come closer and you’ll notice a coterie of dead flies lying at the bottom of the vitrine. I’ll later read that the sugar paper in the cabinets nourished them as maggots, fuelling their careers as live art performers, but by the time I visit their life cycle is complete. A page pinned to the noticeboard excerpts Piero Campores’s ‘The Incorruptible Flesh’, a 1988 text on the bodily mutation and mortification in religion and folklore, most pertinently the Catholic idea that a saint’s flesh resists decay, defying the laws of biology. Flies, on the other hand, are skewered by Camporesi as ‘Beelzebub, the fly-god… protector of witches’ – and if this vitrine is anything to go by, corruptible like the rest of us.

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions (6 Dec 2024 – 5 May 2025), installation view, IMMA – Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. Photo Ros Kavanagh.

On the adjoining walls are minimal drawings on paper. Dashed lines careen from page to page like laser beams: they are joined by crosses and stray body parts – a foot, perhaps punctured by a thorn; an arm; fingers pinching something elusive (an eyelash?); a ruinous yellow spill. We also get the first appearance of the ‘triffid’, a motif Butt would continually return to: a grotesque form resembling a cross between a cartoon scrotum and a small insectoid pest you’d be quick to pluck off your houseplants. Drawn from John Windham’s 1951 science-fiction novel The Day of the Triffids, it occurs across Butt’s work as a harbinger of doom, disease, vitality, destruction. As an opening room for an exhibition, the tone is ominous, puzzling, but presents us with some of the key ideas Butt would continue to elucidate in his brief artistic career: the transformation of the body as it cycles through disease, desire, decay, life, death, and the strained proposition that faith might break this cycle.

Transmission continues in the next room with a circle of glass books, also first shown at Goldsmiths and now part of the Tate Collection. Connected in a ring of wires, each book is prised open and glowing with a UV strip light, harmful to human vision (you can collect protective goggles from a basket on the reception desk). Come closer to the page and you’ll make out a faint etching of a triffid, that ball-sack-like motif that we must follow like Alice follows the rabbit, descending into Butt’s world. The ring formation of the books evokes an absence: where are the readers? The wall text informs us this arrangement references Muslim reading circles, particularly those formed after a death in the community, but even without this knowledge it feels haunting, spectral. A lone box monitor blinks in the corner of the room – grainy video footage of hairy triffids in a toxic waste palette of neon yellow, red, green: the colours of blood and contagion. Usually when an exhibition is described as a ‘visual assault’, it refers to an overload of colour and pattern, a maximalist and busy approach. Butt’s exhibition launches a much more insidious assault on the eyes: literally, in the form of the (mildly) harmful UV light, then more figuratively with his scalpel-sharp aesthetic sensibility, paring a spare, clinical approach to materials with an urgency of message and a preoccupation with death, disease, virality.

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions (6 Dec 2024 – 5 May 2025), installation view, IMMA – Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. Photo Ros Kavanagh.

Upstairs, Apprehensions takes us back in time to the 1980s, presenting Butt’s more formative work – paintings, etchings, and works on paper. Though a departure in materials, the hallmarks of Butt’s singular sensibility are already manifest. The male body and a threat of violence are core concerns, as is a depiction of sexuality as something both alluring and also fear-inducing. Figures crouch or contort, accompanied by muzzled dogs, bare light bulbs, tattooed arms. In one disturbing image, a man appears poised to push a dagger into his eye, facing himself in a mirror. Charcoal life drawings show an economy with line and palette – spare, spiked forms that only suggest a nude. A striking use of red and green foreshadows later work. Across this selection, we witness the disintegration and disembodiment of the figure: by the third upstairs room, it is broken down into just an arm, clutching a handrail as light floods in from a gothic window. Other forms hint at orifices, penises, toilet bowls. As the figure recedes, scientific drawings seem to gain more prominence. Colour is no longer representational but instead suffuses and stains Butt’s drawings like coloured light – a prefigure, perhaps, of the artist’s painterly use of light in his sculptural work.

A vitrine of archival materials shown alongside this body of work reveals opened notebooks, dog-eared paperbacks, photographs, drawings, paperwork, a typewriter-typed statement, even a palm reading (‘emotional … sensitive to a fault, unpredictable, invariably artistic’). This assortment of objects feels intimate, as does the grainy home video filmed by the artist’s brother in the next room. Reclining on a couch, psychoanalysis-style, Butt reflects on his work, its reference points and meanings as the banalities of life buzz on in the background: interruptions from curious children, resetting of the tape, random glitches, the ambient noise of crying babies. It’s a deeply personal antidote to the cold professional artist vox pop we’re used to seeing in museums.

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions (6 Dec 2024 – 5 May 2025), installation view, IMMA – Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. Photo Ros Kavanagh.

Occupying the rest of the exhibition spaces are three monumental works, his Familiars, made in the years following his graduation. Familiars 2: Hypostasis (1992), on the ground floor, is a sculpture composed of three claw-like metal prongs extending skyward, each one ending in a pointed glass tip filled with bromine – an orange-brown noxious chemical used as a disinfectant and nerve sedative. These curved spikes feel both medical and animalic, sending my mind careening through a dizzying set of associations: outsized needles injecting the sky, porcupine spines, cat’s claws, an unsheathed penis. A putrid aroma permeates the room which, combined with the unnerving scale of this object, ties my stomach into knots. The dehydrated-piss brown of the liquid in that glass spike is hard not to flinch at, penetrating the air with a sense of contagion. It’s a punch to the stomach.

In medicine, hypostasis is a build-up of fluid in the body. In Greek philosophy and Christian theology, it refers to the fundamental reality that supports all else, manifesting respectively as a trinity of Soul, Intellect and the One, or Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Familiars, on the other hand, is an occult term for a shape-shifting spirit, usually in animal form, that accompanies a witch (black cats, crows and the like). In this context, the work could evoke a triumvirate of witches hunched around a cauldron. Butt was fascinated by alchemy, and what was lost when that mystical, eccentric discipline was stripped of its more supernatural, mystical associations and became rationalised and tamed into what we now call ‘science’. Alchemy (from the Arabic ‘al-kimiya’, meaning ‘the art of transformation’) is fixated on the changing of forms: most famously base metals to gold, but also various other processes of crystallisation, evaporation, sublimation, and distillation that we see unfold across Butt’s work. For Butt, this always links back to the body, its transformation, decay, and the possible ascension or transcendence of a soul upon death. Originally titled Familiars: Arch, the work also references the history of Islamic architecture with its distinctive arch forms, revealing a rich constellation of references lurking behind the minimalist exterior of Butt’s work.

Hamad Butt, Familiars 3: Cradle (1992). Installation at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, 1992. Vacuum-sealed glass, crystal iodine, liquid bromine, chlorine gas, water and steel. Overall display dimensions variable. Courtesy John Hansard Gallery and Tate.

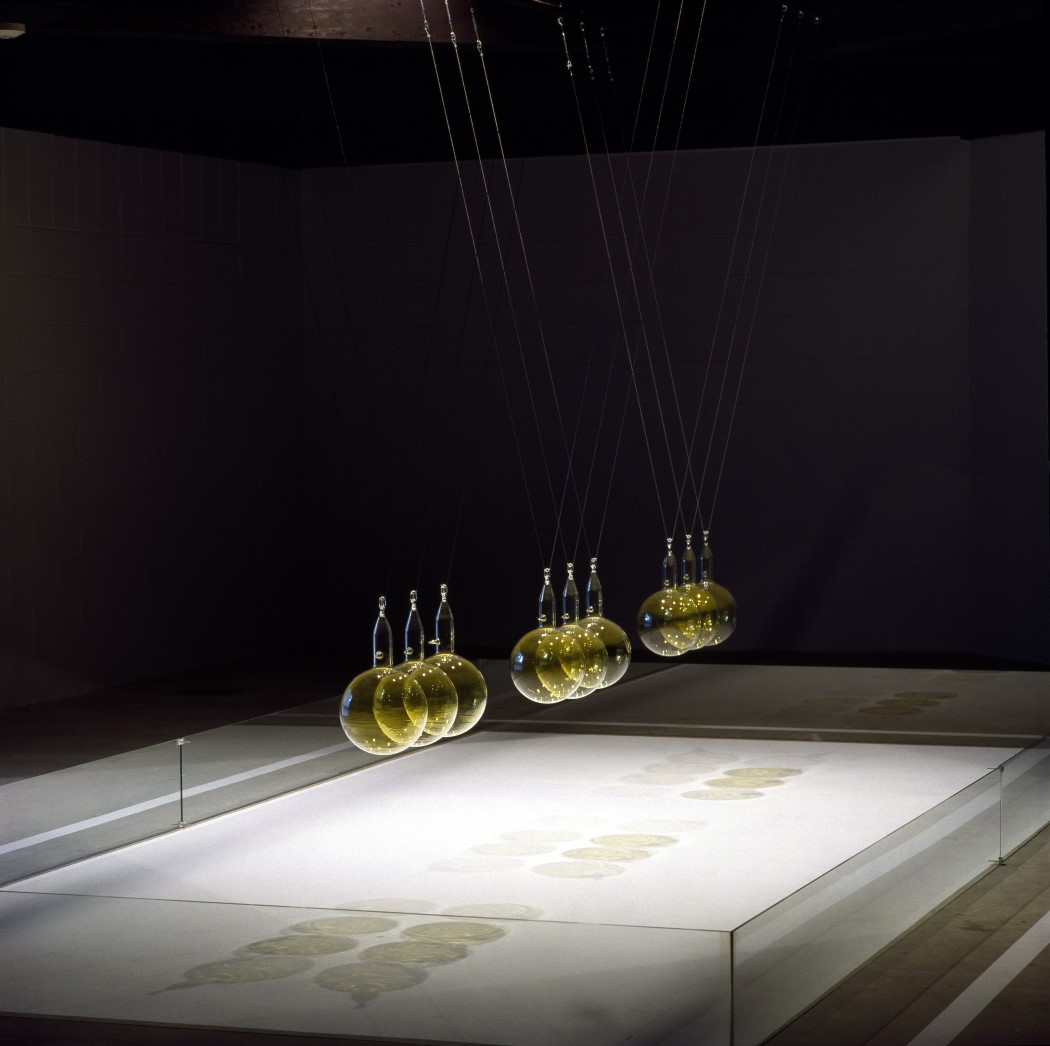

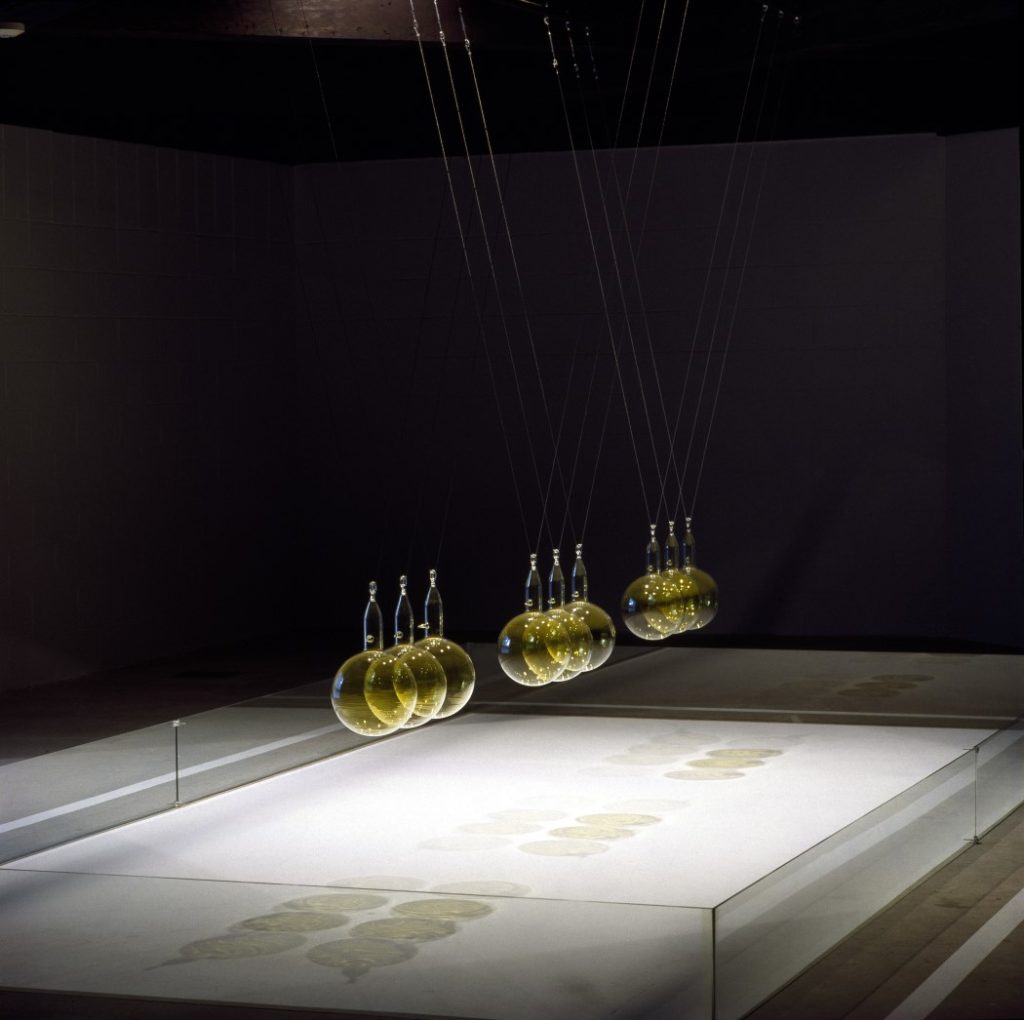

The other Familiars are housed in the basement gallery. Familiars 3: Cradle (1992) comprises nine glass orbs, delicately suspended in a line, each one filled with chlorine gas, another harmful chemical that is used for sanitisation. On a sunny spring day, light from the skylight floods the room, giving this work an ethereal quality and casting yellow shadows on the ground. Its citrine glow brings to mind a stained-glass window, with all its spiritual baggage. This work is minimal, light, delicate, heavenly, airy, and yet toxic at the same time, teetering on the edge of fear and beauty. The glass baubles are smooth, sculptural, each one resembling a little balloon of poisoned breath. In one of the catalogue essays, Dominic Johnson points out that the liquid and gaseous elements in Butt’s ‘are older than us, and will outlive us, as they were formed in cosmic time’. [1] These nine suspended glass spheres, appearing to float in air, do conjure the cosmic. They’re modelled after Newton’s cradle, a desktop toy demonstrating the laws of physics, but also bring to my mind an interplanetary model, or minimalist solar system.

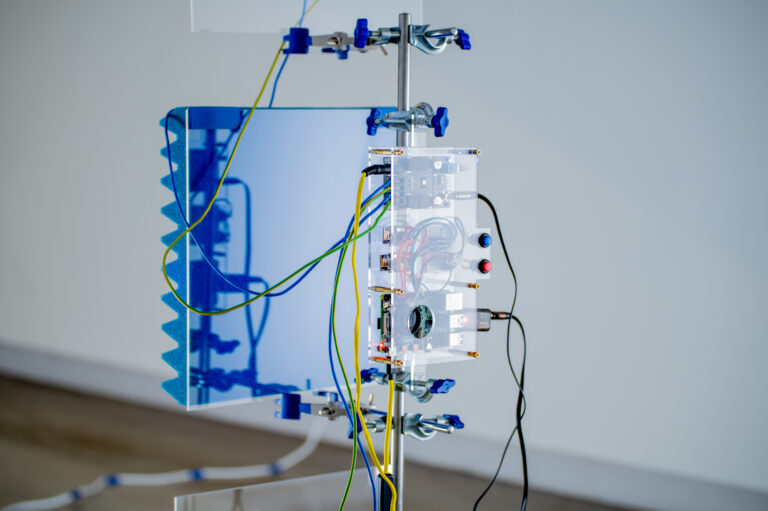

In the same room, stretching upwards towards the skylight, is Familiars 1: Substance Sublimation Unit (1992), a ladder-like sculpture, each rung a glass vial filled with iodine crystals and a strip of heat lamp. Programmed in a sequence, they flare red one by one, ascending in order. Here, Butt’s dashed line drawings trail off the page and into the rungs of the ladder, each one glowing red with an intensity that stains your vision as you look away yet compels you to look longer, to orbit the work and feel the heat on your skin. Wires curl around the rungs of the ladder, connecting the circuitry, but feel medical, like breathing tubes or IV drips. The work is perhaps the most explicitly religious in its reference – the ladder of divine ascent offering the path to salvation across Abrahamic religions. As Butt points out in his text ‘Indications’, it is ‘the holy ladder to perfection necessitating the abjection of the body’. [2] The iodine crystals in each vial are, again, used in sterilising tinctures but are highly toxic; here, they are transformed from crystal to gas to crystal again in a perpetual cycle, skipping liquid form, their literal sublimation mimicking the ascension of a soul. I think of Renaissance paintings of ascensions, bodies transcending their mortal, corruptible flesh to become heavenly, airy. And yet, it’s hard to see this work as entirely hopeful: each rung of the ladder offers potential escape, ascension, but would also burn your hands, feet, eyes as you climb. The feeling is less panacea, more ‘pharmakon’, the experimental treatment that kills as it cures.

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions (6 Dec 2024 – 5 May 2025), installation view, IMMA – Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. Photo Ros Kavanagh.

Later I’ll look at photos of these fear-inducing works as they were installed at Milch Gallery, London, in 1994. At the private viewing, crowds of cool kids spill around the suspended glass orbs of Familiars 3: Cradle (no barriers!) sipping cans of cheap lager. Outstretched arms freely brandish lit cigarettes; out of frame, dogs reportedly run around unleashed. At the time the photograph was taken, Butt was still alive but was too sick to attend. [3] In another outing, at John Hansard Gallery in the 1990s, a hazmat suit and gas mask were supposedly installed nearby, in case of an incident. When Familiars 1: Substance Sublimation Unit was shown at Tate in 1995, one glass rung of the ladder actually did malfunction, and the gallery had to be evacuated. This led to a critical outcry among an outraged tabloid press, for years skewing readings of Butt’s work towards the sensationalist, reductive, and harming his artistic reputation. The risk associated with exhibiting Butt’s work, alongside his marginal identity as a Pakistani, Muslim, gay man, perhaps explain why his powerful work hasn’t been more widely exhibited and recognised in the years since his death.

I find myself tempted to trace parallels with Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the Cuban-American artist who died of AIDS in 1996. Besides the circumstances of their death, the artists shared a minimalist, ascetic, and yet somehow sensuous approach to materiality; a preoccupation with the male form; a penchant for light/light bulbs as a material; and time-based artworks that decay or alter during the case of an exhibition’s run (Butt’s dying flies, Gonzalez-Torres’s continually diminishing pile of sweets). Precarity drives both, but while Gonzalez-Torres’s work is ultimately governed by love, intimacy and generosity, Butt’s world is more nihilistic, afraid, tinged with violence. Sex offers not salvation but a death drive (‘To be intimate,’ he wrote, ‘is, / after all, the ultimate end’). Of course, Gonzalez-Torres left behind a larger body of work, an outcome of a brutal metric: Butt died at thirty-two, Gonzalez-Torres died at thirty-eight. Both were tragically young, but with Butt’s definitive work produced in a short period between 1990 and 1994, it’s impossible not to wonder what he might have produced had he been afforded even just six more years. At a recent talk, writer Charlie Porter commented that we must not only mourn the known – those artists, thinkers, and makers who managed to achieve recognition during their lifetimes – but also the immeasurable unknown, those who died before they had a chance to develop an artistic identity, or begin making work. In a sense, Butt falls into both of these categories: though he achieved some recognition in his lifetime, and clearly made some striking work, his journals, interviews, and archival materials demonstrate that he had many more ideas that never saw fruition: ‘I have kind of like big projects that I know it will take a couple of years to realise,’ he tells his brother in the home video. In the last year of his life, he was interested in working with sound, video, and publications, but was ultimately too ill to follow through with his plans. Apprehensions offers something both mournful and invigorating, celebrating the condensed oeuvre of an exciting, genuinely innovative and fearless artist, while also lamenting what was not to be.

Rosa Abbott is a writer and curator based in London.

Notes

[1] Dominic Johnson, ‘Hamad Butt: “I Want to Speak of Fear”‘, in Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, ed. Dominic Johnson (Munich: Prestel, 2024), 28.

[2] Hamad Butt, ‘Indications’ in Apprehensions, 172. Butt wrote this text in 1991 to theorise his work on Familiars. It is published for the first time in the exhibition catalogue for Apprehensions.

[3] Johnson, ‘Hamad Butt’, 25.