Alice Rekab’s exhibition, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, is a family reunion of sorts. As ‘the white-passing child of a mixed marriage, born into a very white space’ [1], the artist’s Irish and Sierra Leonean ancestors, displaced and dispersed through generations of migration, congregate in Sirius Arts Centre, itself a historical point of embarkment (albeit known, more recently, as a destination for cruise ships). Curated by Miguel Amado, the exhibition features an exhaustive array of objects and images, including personal mementos, family photos, repurposed materials, sculptures, prints, and films. The silhouette of Rekab’s father is drawn on the headboard of a broken bed-frame. A lopsided clay table bears an academic textbook on West African literature. Moulded masks and figurines stare out from corners, niches, and stairwells. For the viewer, whose initial knowledge of Rekab’s background might be limited, the effect is one of dawning identification with the artist’s own digressive trajectory, where fragments of stories are investigated, extrapolated, and unravelled, without ever being wholly reconstituted.

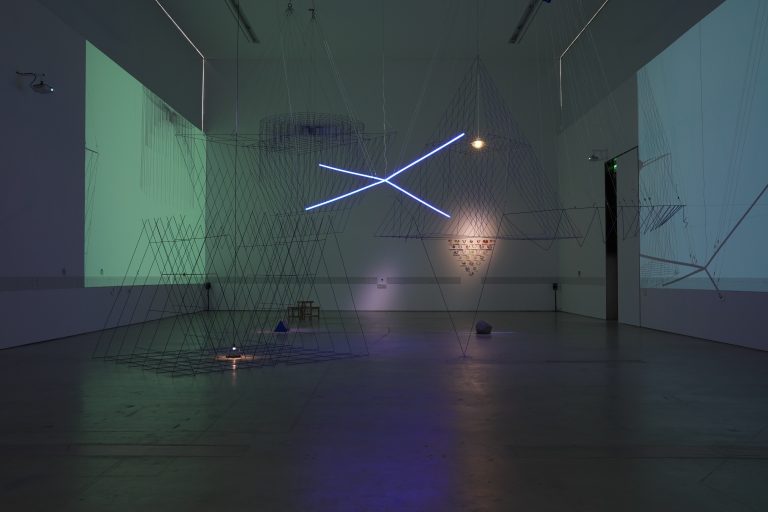

Alice Rekab, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Sirius Arts Centre. Photo: John Beasley.

The works accrue over the course of multiple exhibitions (Rekab has shown several of the pieces previously, in Munich and Dublin, while forthcoming iterations of Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics are scheduled for Galway, Drogheda, and Limerick), expanding in both quantity and resonance. Each item carries a legacy, as it adapts to different locations, switches neighbours, even acquires knocks and bruises. A series of wooden boards, sawn with shallow grooves and arcs, were retrieved from Rekab’s shared studio complex in Dublin. To these, the artist has added thick clods of clay, smeared and scumbled across their surfaces. Faded scraps of inkjet prints have been applied onto the timber, and effaced, in turn, with oil pastel. Faint outlines of spectral presences are rendered illegible through swathes of white paint, flecks of clay, and smudged chalk. Entitled Our Common Ancestor: Five Panels of Enmeshed Historical Narrative (2022), the work bears the scars of its past owners and usages: functional object to scrap material, page to palimpsest.

Alice Rekab, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Sirius Arts Centre. Photo: John Beasley.

As in the sculptures here – totemic figures, animalistic footstools, snakes, and lizards – the use of unfired clay, which compresses and cracks over time, imbues the works with a sense of contingency. A crocodile’s carapace is pocked with evident fingerprints. Serpents are squeezed into crude tubular forms. The hollows of eye sockets and mouths fit neatly into the grip of the artist’s hands. As Rekab has explained, these animals are ‘interpretations of the souvenirs that were in [their] family home, objects that had been brought over by [their] father’s family in the 1960s as symbols of their culture’. [2] The artist’s versions, with their tactile traces and crumbling grey and white skins, evoke a capacity to be remade, manipulated, and modified, as if momentarily arrested in a state of indeterminacy. In addition, their symbology – drawn from Sierra Leone’s admixture of Muslim, Christian, and indigenous religious beliefs as well as Ireland’s own passage from paganism to Christianity – embodies syncretism, that inevitable melding of traditions that accompanies migration, whether voluntary or coerced. Intriguingly, the colonial ‘founding’ of Freetown in Sierra Leone is itself an example of diasporic settlement from across the Atlantic: Black Americans who had escaped slavery to Nova Scotia during the Revolutionary War were subsequently granted the right to resettle in Britain’s West African colonies.

Alice Rekab, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Sirius Arts Centre. Photo: John Beasley.

An adjacent room resembles a domestic study, a hearth painted in dark tones with various books and DVDs on post-colonialism by Frantz Fanon, Stuart Hall, and Edward W. Said, among others, displayed on the mantelpiece and cabinet. The hose of an antiquated Electrolux hoover has transmogrified into a snake. Beanbag chairs are splayed across the floor in front of a large film projection of footage taken by Rekab in Freetown. Christmas on Cemetery Road / Hamilton (2021) is a raw, seemingly unedited, compilation, including shots of coastal views and family conversations, slow pans across bookshelves, close-ups of interior settings. Rekab has referred to it as a ‘video dump’, as if warily excusing themselves from imposing a specific narrative to the flurry of discordant images. As Said has written: ‘The power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism, and constitutes one of the main connections between them.’ [3] To repudiate this power and allow the text to remain open-ended and unresolvable is itself a statement of intent.

Alice Rekab, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Sirius Arts Centre. Photo: John Beasley.

Layered across the gallery floor, A Thinning of the Veil / Broken Reflections from Memory and Dreams (2023–24) comprises an arrangement of mirrors overlaid with various clay sculptures: brown and white encrusted tubes, a death mask, a family of crocodiles, leaves, and fingers. They seem to skim across the surface, or in some cases, to partially emerge from beneath this reflective pool. Captured in the mirror are echoes of surrounding paintings, overhead architectural details, the occasional glimpse of looming visitors. The installation hints at a bottomless surfeit of recollected elements, gradually – and partially – salvaged from an unfathomable reservoir. An adjacent display of wooden boards, casually leaning against the wall, is scored with deep incisions, swathes of paint and pastel, branches, stars, comets, and a framed portrait of the artist’s paternal grandmother, Isatu Kallokoh, her face obscured by coiled rope. In You Could Not Choose the Star You Were Born Under (2022), history is registered through archival images and aspects of Rekab’s own, personal cosmology. The work’s title, like others here, poetically alludes to past events, withholding as much detail as it provides. In fact, given the absence of individual wall labels and the immersive, indiscriminate nature of the displays, the exhibition more closely resembles a single expansive installation, a ‘Wunderkammer’ of curiosities, relics, inherited objects, and family heirlooms.

Alice Rekab, Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Sirius Arts Centre. Photo: John Beasley.

It is fitting then that Clann Miotlantach / Mythlantics finally delves into the recesses of SIRIUS itself, opening up its basement spaces as an extension of the exhibition. In its winding, subterranean alcoves, a body of works revolves around West African nomoli, miniature soapstone figurines that were said to have formed underground before being unearthed by farmers and miners. As the accompanying film explains, the discovery and reburial of these objects was believed to bring a bountiful harvest. In Rekab’s installation, the motif is repeated, reproduced, and collaged across digital prints, hovering in space, set against a field of other nomoli, drawn over and scratched out. It keeps returning, refusing to disappear completely; an unrelenting embodiment of repressed memories.

Chris Clarke is a critic and curator based in Cork.

Notes

[1] Alice Rekab, ‘Family Lines’, Visual Artists’ News Sheet (July–August 2022); see visualartistsireland.com/column-family-lines.

[2] ‘Home, Architecture, Territory: Miguel Amado Interviews Alice Rekab about Evolving Thematic Concerns in Their Practice’, Visual Artists’ News Sheet (March–April 2023): 17.

[3] Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), xiii.