In April 2019, I began a research project in collaboration with the Centre for Experimental Archaeology and Material Culture at University College Dublin (UCD). This was the start of my current research on the human hand and its role in the advancement of machine learning. In the past number of years, much of my research has focused on the use of artificial intelligence to mimic human behaviour and thinking, exploring the role of artificial intelligence in our everyday lives and finding ways to discuss the complex network of physical, virtual, and hybrid interactions that we, as a society, now experience with AI.

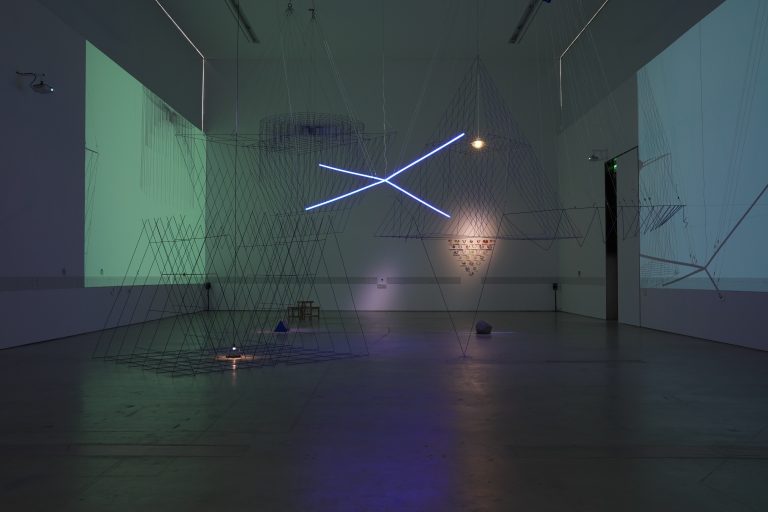

David Beattie, Robots in Residence, 2021

Research image; courtesy of the artist

Through the project with UCD, I wanted to explore the process of tablet weaving as a means to discuss the historical connections between the loom and computation. In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a power loom that could base its weave on a pattern automatically read from wooden punch cards. My research began by looking at the effect the Jacquard loom had on labour within the nineteenth-century textile industry, eradicating the need for manual labour and shifting it towards an automated industry. How will the development of artificial intelligence and automation impact future human labour? This process resulted in a temporary public event along Derry’s historic city walls in September 2019. Working with CCA Derry~Londonderry, I hosted weaving demonstrations alongside an augmented reality artwork that could be accessed at various points in the city via a smartphone. Gathered under the umbrella title of The Company of Others, this open-research project – initiated by CCA Derry~Londonderry and undertaken with artist Alan Phelan – focuses on relationships between colonialism, capitalism, and material culture, using Derry’s history as a starting point. In June, a limited-edition box, which includes a clay cup produced by Alan Phelan and a QR-activated artwork by me, was launched to reflect the ongoing research and events of the past two years. [1]

Following this project, I became interested in finding ways in which the human hand interfaced with machines – the ways that our touch, our fingertips have become integral to the further advancement of the machine. I had begun to think about this in various ways pre-COVID-19, but the pandemic very quickly became all I could think about in March 2020. Suddenly what we touch and what we can’t touch became paramount to the health of the population. The necessity to retreat from shared spaces and physical interactions pushed us further towards hybrid, non-physical interactions. This, in turn, contributed vast amounts of information on how we work, how we eat, and how we communicate to the listening machines and their algorithmic processing of this information. It was exactly these points of contact with deep neural networks and machine learning that led me to work with the Science Gallery Dublin and Trinity College, exploring haptic robotics and object recognition during a short but intense residency in May 2020.

An interest in exploring the ways we engage with the physical world has been a constant in my practice throughout the years. In particular, it is the transition from one interaction to another, a metamorphosis of form from one state to another. Influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s concept of ‘infra thin’, summarised as ‘the immeasurable gap between two things as they transition or pass into one another’, my practice has often explored the material world through experiential, physical engagements with objects, the inherent connections between objects. [2] How a thing comes into contact with another living and non-living thing. In Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s recent book Thin Places, she discusses the presence of thin places, a space, a place, a moment when the liminal space lets you to access your inner self or rather to the forgetting of the idea of self. Speaking primarily of nature, she talks about being:

In a place where manmade constructs of the world seem as though they have crumbled, where time feels like it no longer exists, that feeling of separation fades away. We are reminded, in the deepest, rawest parts of our being, that we are nature. It is in and of us. We are not superior or inferior, separated or removed; our breathing, breaking, ageing, bleeding, making and dying are the things of this earth. We are made up of the materials we see in places around us, and we cannot undo the blood and bone that forms us. [3]

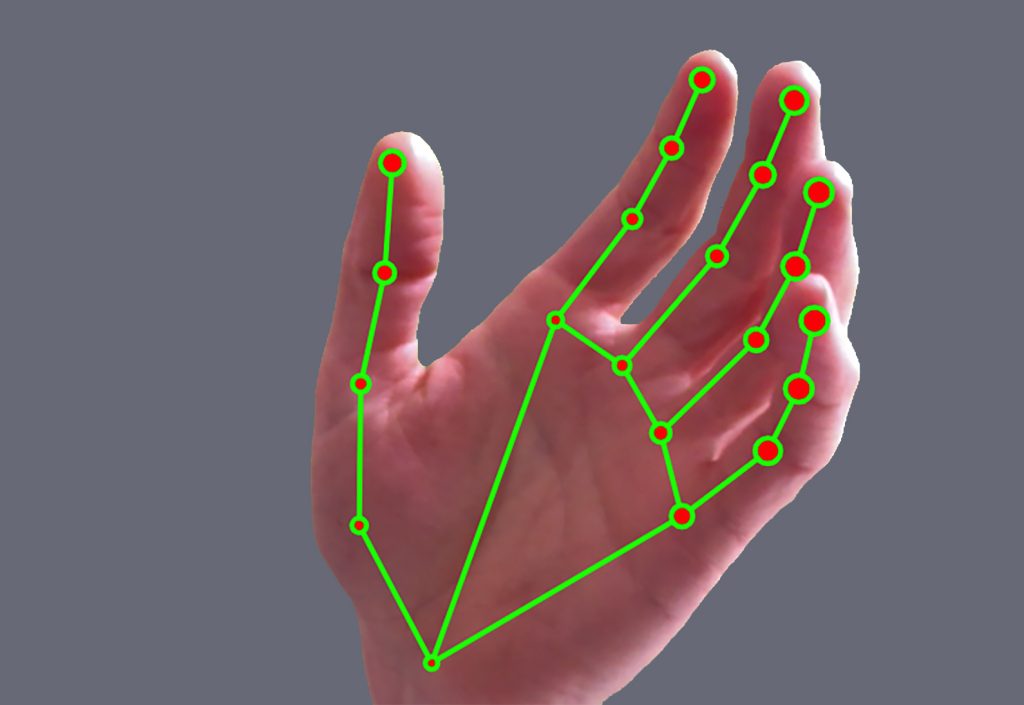

David Beattie, hand tracking, 2021

Research image; courtesy of the artist

I look to explore these points of contact with the machine world in similar ways. How do our interactions and engagements with the machine world inform ways to discuss the thin place between nature and the machine, and at what point are we one and the same?

The robotic machine can take many forms: humanoid with a friendly face or industrial and functional. For the purposes of my residency at Trinity College last year and more recently through a research project with the Goethe-Institut in Dublin, I was keen to explore the failure of the robotic hand. The mechanics of the human hand, although complex, are relatively easy to replicate. Skin, however, is the body’s largest organ and has a key sensory role in touch, and to date this has been the last frontier of robotic engineering. Skin plays a large part in how we react to objects, sense texture, temperature, and so forth. The continuous tactile feedback and hand articulation enables us to engage and navigate with multiple forms and objects as we come upon them. This inherent proprioception (the sense of self-movement or body position) is also informed by years of inter-generational muscle memory and makes for a very complex ‘machine’. [4]

Then in March of this year, I was given the opportunity to take part in a European-wide project Generation A=Algorithm, through the Goethe Institut and Science Gallery. It was a short six-week period where I collaborated with computer scientist Niamh Donnelly from Akara Robotics to research various outcomes with a humanoid robot called NAO. [5] We focused on the robotic hand, what it can and can’t do. This evolved as a series of tests on textures, shapes, and sizes of ‘natural’ objects, exploring the idea of manual labour or hand-based work via the machine. What can a robotic hand achieve that a human hand can’t and vice versa. The premise of the wider project was to send the robot to multiple locations around Europe to work with artist/coder teams, potentially discovering interesting ways to think about robotics or test its capabilities outside of the parameters of the science/robotics world. Interestingly, due to travel restrictions across Europe for the past year, the robot as a non-living organism was able to travel from place to place while the human participants could not. It’s sterile, non-living state, resistant to virus growth and transmission, is a further reminder of the future role of the machine among living things.

David Beattie, MANO model, 2020

Research image; courtesy of the artist

A humanoid robot like NAO is reliant on image, object, and voice recognition to engage with its surroundings. As the role of image/object recognition becomes more embedded in our everyday, I am interested in the types of data being used to inform the process of computer vision and machine learning. Increasingly these data sets and algorithms are being questioned in terms of the quality of the data. How do you generate algorithms that do not reproduce or even reinforce prejudices? Through my research with NAO, I was keen to explore design considerations for assistive technologies, the role of the less-able hand and how image/object recognition is used to enable adaptive motor function.

I am currently bringing together a number of these recent projects about haptic feedback, the embodied hand and AI, culminating in a public outcome in autumn 2021. Examining the MANO model (hand Model with Articulated and Non-rigid defOrmations) as a base for 3D hand movements

I am creating a new body of work that can explore hand interactions in the virtual, mixed, and augmented worlds. How do we experience haptic feedback when interacting with virtual objects? As we seamlessly hop from IRL to URL multiple times a day, [7] I hope that through this work I can discuss the complex network of physical and non-physical interactions we now experience as a society, the biological effects this may have through biomimicry, and the role of the physical body in future labour and automation.

David Beattie is an artist who lives and works in Dublin.

This essay was originally published in PVA 12, our touch-themed edition.

Notes

[1] See CCA Derry~Londonderry’s website for more details on the project.

[2] Infra thin (Infra mince) is an elusive theory proposed by Marcel Duchamp who famously refused to define it, believing language to be inadequate but rather gave numerous examples of what it could be i.e., ‘when tobacco smoke smells too like the mouth that exhales it, the two odours marry by infra mince (olfactory infra mince)’. Marcel Duchamp, ‘inframince notes’, trans. Rebecca Loewen; see here.

[3] Kerri ní Dochartaigh, Thin Places (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2021), 54.

[4] Sara Baume, referring to William Morris’s ‘Useful Work versus Useless Toil’ (1882), talks about ‘hands that know what they must do without instruction, that the objects shaped by their ancestor’s phalanxes and phalanges and metacarpals for thousands of years remain in the memory compartment of their tiny brains, in the same way as birds know which way to fly without being guided or following a plotted course, without a book that provides detailed drawings and plans with parts to accompany it.’ Sara Baume, Handiwork (Dublin: Tramp Press, 2020), 126.

[5] For more info on NAO, see the Soft Bank Robotics website.

[6] More info on the MANO model here.

[7] IRL is an abbreviation of for in-real-life experiences; a URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is generally referred to as a web address or an online location.