Helena Hamilton

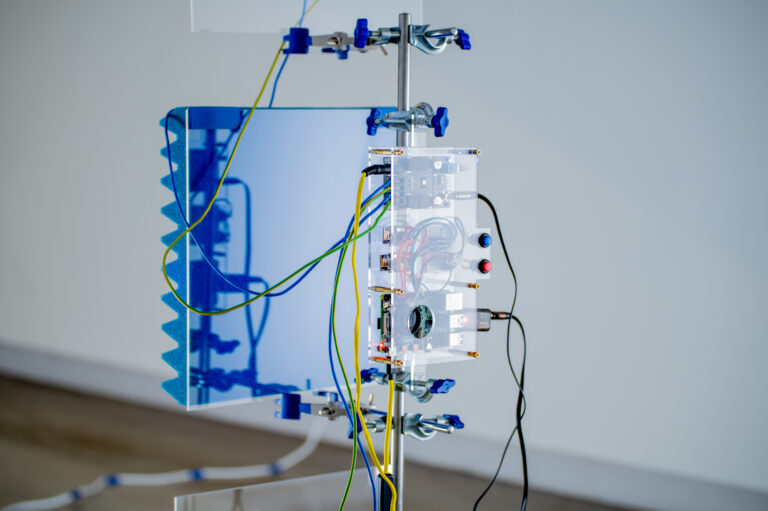

Untitled (With)

2018

Interactive, site-specific light and sound sculpture

Dimensions variable

Photo: Simon Mills

Belfast is a city that – blighted by opposing politico-religious tensions – has historically found connection and togetherness through sound. Whether it be the punk anthems of Stiff Little Fingers, or the ecstasy-fuelled dance scene of the ’90s, led by DJs like David Holmes, audio culture has bridged divides in Northern Ireland, proposing an alternative to the soundtrack of bomb blasts and gunfire produced during the Troubles conflict.

Acoustic territories provide a different way of thinking about space. Take church bells, for example, which have served important social functions in European societies for centuries. Ringing out the passing of time, the union of marriages, and occurrences of death within a community, church bells have also functioned as important signifiers of space, marking out a sense of place for inhabitants of the surrounding area. During the late 1700s in Lyon, France, churches within different parishes had bells tuned to different notes to remind locals of parish boundaries. [1] Church bells were signifiers of protection and power. The sound of these bells was a way for the church to declare: ‘this is our territory’.

Nevertheless, the ‘acoustic territory’ communicated by church bells was never as rigidly defined as the official parish boundaries would have been seen on surveys or maps. As far as it goes, sound can be a volatile thing. Depending on wind direction, climate, and other factors, a French native might have heard their parish’s bell from a particular place on one day of the week and another parish’s bell on another. The borders between two places would have shifted as the wind took it.

Collectivity and Experimentation

The DIY attitude of punk, as well as the collectivism of dance music, permeated Belfast’s visual arts scene in the early 1990s, via artist-led spaces like Catalyst Arts. Established in 1993, Catalyst Arts became a vital node for artistic experimentation in the city. Dan Shipsides – a codirector at the gallery from 1996 to 1998 – recalls that Catalyst ‘wasn’t as worldly [as it] is now. It was more of a social scene. The gallery was really a club’. As well as hosting exhibitions and facilitating art projects, one of Catalyst’s longest running events was Club Curious – a secret music night, announced by word-of-mouth to friends of the gallery. Shipsides recalls that while the club night drew on the energy of the house-music scene in Belfast, it operated differently, eschewing the authority of the DJ for a more art-school sensibility, playing ‘really interesting music … from Throbbing Gristle right through to Madonna’. He recalls that ‘there was sense of sound art and an understanding of what that was, but it wasn’t anything pure … It was more like “let’s just try this”. Plug this thing into this thing and layer it. Just experiment’. In this way, sound-based art practices began to take hold in Belfast.

The lack of a viable art market in Northern Ireland meant Catalyst’s spirit of experimentation flourished, forging a reputation for the championing of performance, video, sound, and other time-based art practices. Among the happenings at Catalyst that resonated most with Shipsides was a twenty-four-hour durational performance by Kevin Henderson, Ghost Dispenser, which took place from 17 to 18 October 1995. For this performance, Henderson installed a high-tension wire across the gallery space, from one wall to another. Dressed in black (‘as performance artists did in those days’), Henderson also wore a balaclava with a metal hoop stitched on top, which the metal wire ran through. Over the course of a full day, he moved along the wire – unable to stop or rest – while sporadically playing the clarinet, each note and musical phrase becoming more laboured as fatigue set in. For Shipsides, Henderson’s performance opened the possibilities between art making and music – a fusion Shipsides still pursues in his own practice, where he melds sound, video, and installation, in partnership with his collaborator, Neal Beggs, as Shipsides and Beggs Projects.

Shipsides now teaches at Ulster University and runs the Belfast School of Art’s MFA alongside Mary McIntyre.[2] Both share a passion for sound and music, which they inject into their teaching. He notes that students have recently become more interested in using sound in their work, perhaps due to a democratisation of affordable sound production technology – like field recorders, laptops, and audio software – which has opened up the material potentials of sound, allowing people to collect and manipulate recordings in more accessible ways.

Another potent example of Catalyst’s influence on Belfast’s sound-art scene comes from another previous codirector, Susan Philipsz. Arriving in 1993 to complete her MFA at Belfast School of Art, Philipsz became involved with Catalyst when it formed the same year. Her work in Belfast focused on using her voice and presenting it within different contexts, as a way of tapping into different connotations or functions of a given place. An example of one such Belfast-era work is Filter (1999), where Philipsz recorded herself singing ‘Airbag’ by the band Radiohead, which was recurrently broadcasted from the public-address system installed in Belfast’s Laganside bus station. Many years after leaving Belfast, Philipsz would become the first artist working solely with sound to win the Turner Prize for Lowlands (2008/10). The piece was presented as part of the 2010 Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art and consisted of recordings of Philipsz’s singing the Scottish ballad ‘Lowlands’, which was played via a set of speakers installed underneath three bridges in Glasgow. The impact of Philipsz’s Turner Prize win remains highly symbolic, both for Belfast and for sound-art practice in general. To a certain extent, it legitimised the singular use of sound as a form of visual-arts practice. It also demonstrated the importance of Catalyst’s artist-run model, as an incubator for artistic talent. The Turner Prize win also gave kudos to University of Ulster’s already respected Belfast School of Art.[3] But by the time Philipsz won the Turner Prize, sound art was already gaining traction as a discipline in Belfast.

Academic Perspectives on Sound

The Sonic Arts Research Centre (SARC) was established in 2001 at Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) as an institute for sound-based practice and research. The expertise and interests of the centre are multifaceted. Sound recording, production, and musical composition take centre stage, supplemented by investigations into instrument design (particularly ‘new musical interfaces’, which use sensors and other new technologies to transform musical performance), as well as research into the sonic aspects of the built environment and projects that seek to use sound-based practice as intervention strategies within different contexts. Where Catalyst Arts in the ’90s encouraged a naïve DIY attitude to sound, SARC became instrumental in formalising sound art as a practice with an academic outlook. It has also served to connect Belfast with an established international scene of expanded sound-based practices – such as musique concrète in France and Klangkunst in Germany.

SARC’s crown jewel is the Sonic Laboratory – a state-of-the-art, tailor-made space that allows for immersive, three-dimensional presentations of sound. From an engineering standpoint, the room is a marvel: a metal-grid floor suspends the audience above a lower-level basement section, housing the first of a set of forty-eight speakers that surround the room’s entire perimeter. The Sonic Lab was officially opened in 2004 by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen – a significant if somewhat eccentric figure in twentieth-century classical music. Stockhausen’s inauguration of the building was accompanied by a series of performances of the composer’s work, which took place in QUB’s Whitla Hall and coincided with Sonorities Festival. As one of SARC’s main public events, Sonorities Festival brings international composers, musicians, and sound artists to Belfast for one week. Starting in 1981, it was originally run by the School of Music at QUB as a contemporary music festival. When SARC and the Sonic Lab were built, the festival underwent a transformation and its focus changed into a celebration of these spaces and the affordances they offered for presenting work. This shift in focus crystallised in 2008, when the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) coincided with the festival, with over two thousand international composers and researchers converging in Belfast.

Simon Waters lectures at SARC and has been involved in the curation of Sonorities Festival since 2012. As well as being an academic and electroacoustic composer in his own right, Waters has had an extensive involvement in the arts, studying physical theatre and later working on music commissions for dance companies. His parents were visual artists and worked in art colleges. These experiences informed Waters’s approach when he took over the reins at Sonorities, introducing a ‘poly-sensoriality of experience’ that aimed to dispel the idea that musical events should only be about auditory experience. Sonorities started expanding outside of concerts and listening events in the Sonic Lab, to include installations, exhibitions, screening events, and club nights, which have so far taken place in galleries, museums, and other venues across the city. Where pre-2012 festivals seemed more exclusively aimed at academic audiences, recent editions feel much more inclusive and open to the general public.

Sonorities Festival 2018 involved an extensive programme of events in the Sonic Lab, as well as exhibitions in venues across the city, including Framewerk art gallery, QSS Gallery, and a live cinema performance of The Mirror (2018) by People like Us (Vicki Bennet) at Crescent Arts Centre (programmed in partnership with the Belfast Film Festival). A highlight of the 2018 festival was House Taken Over, curated by Ciara Hickey and Nora Hickey M’Sichili in their family home on Malone Road. The exhibition’s conception came from the discovery that their house was used as the Northern Ireland Intelligence Headquarters during the Second World War. Known then as Heathcote House, operatives based there would log information of enemy radio communications and forward these records to Bletchley Park for decryption. The works featured in the exhibition tapped into this idea of covert communication and spying. As a viewer, I felt implicated in the clandestine acts of listening and looking, while hunting for artworks concealed in parts of an otherwise functioning family home.[4]

Radiating from the Source

SARC’s impact on Belfast’s wider arts scene has been incalculable. Students coming through the centre’s undergraduate and postgraduate programmes have gone on to establish careers as musicians, composers, and visual artists; they have also set up record labels (for example the label RESIST, formed by Koichi Samuels). A new sound art collective, Umbrella, also operates through SARC, incorporating students, staff, and other artists interested in sound-based practices (me included). The collective aims to assemble a diverse range of practices by hosting anthology-style events in various settings. A recent climate change–themed showcase took place in the Soundscape Park Project – a small community garden in East Belfast that has twelve permanently installed outdoor speakers, for the transmission of sound – developed as a collaboration between SARC and Businesses in the Community NI.

One emerging artist to have benefitted from SARC’s training is Helena Hamilton. Originally studying at Belfast School of Art, Hamilton’s work began to shift towards sound-based ideas after a Graduate Residency at Belfast’s Flax Art Studios, after which, she undertook a taught MA in Sonic Art in 2013.[5] Hamilton concedes that her experiences at art college differed dramatically from her time at SARC, which she felt, at that time, was more focused upon compositional practice, with her classmates coming from disciplines involving music, sound design, and computer coding. She was the only student who came from a fine-art background. Nevertheless, her tutors (one of whom was Simon Waters) were encouraging, and Hamilton developed new strands of practice by incorporating complex, real-time generative aspects to her work by using computer programmes like MAX MSP. One performance-based work developed during this time was The Butterflies in My Brain (2014). The piece involves drawing onto an overhead projector, which houses four different microphones. A webcam maps where Hamilton draws, with different microphones being selected and filtered to create varying, real-time soundscapes. After submitting this work for assessment, Waters asked Hamilton to perform it as part of that year’s Sonorities Festival. I experienced the work as video piece within Hamilton’s solo exhibition Semblance and Event, which ran in 2018 at Millennium Court Arts Centre, Portadown. The exhibition vibrantly showcased the breadth of Hamilton’s practice, exploring the tactile interactions between the auditory and the visual, incorporating video, interactive sculptures, and works on paper. The centrepiece was her light sculpture, Untitled (with) (2018), made from a set of suspended florescent light bulb tubes, accompanied by a soundtrack composed of buzzing light sounds, which slowly evolves with subtle changes in light within in the gallery space. Hamilton is a prime example of an artist who has carved out a delicate niche for herself, between visual and sonic realms, in which she has been able to create original and compelling works.

To this day, Catalyst Arts continues to promote sound-art practices. A current SARC PhD student, Liam McCartan, is now also a codirector at Catalyst Arts. He has shaped Catalyst’s programme to include a strong sonic element and closer ties to SARC generally. A new series of listening events and online releases, called Catalyst Audio Tracks, began in August 2018, with a co-occurring listening event taking place in the Sonic Lab. The first exhibition McCartan curated for Catalyst Arts was Synthesis, which took place in 2018 and brought together a diverse group of artists and electronic musicians. Catalyst codirectors facilitate one long-running ‘director’s show’ before they step down. McCartan’s director’s show, Resonance, was unashamed in its reverence for the visceral physicality of sound. A singular black structure – not unlike the monolith seen in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – filled the void in the middle of Catalyst’s white-walled gallery space. Emanating from this structure where pieces by artists Sunn 0))), Holly Herndon, T. J. Hertz, and Phurpa, which each seemed to test the acoustic limits of the space; broadband sonic impulses that set parts of the room into literal vibrating motion. After visiting the exhibition, I prayed that Catalyst’s building would still be in once piece when I next returned. John Macormac was another codirector of Catalyst Arts from 2016 to 2018. He is also the drummer for the experimental math rock band Blue Whale. The densely orbiting rhythms found in Macormac’s drumming style feed into his own work as a visual artist, which has begun to incorporate fractal-based drawings. Macormac’s final director’s show before he left Catalyst in 2018 was titled Interzone – an exhibition that actively sought to question the borders between different artistic mediums, showcasing work where the visual and auditory bleed into one another. Interzone included works by stalwarts of the current Belfast scene, such as Barry Cullen – who presented his excursions into audio and visual feedback using homemade electronics – while also hosting works by artists from further afield, such as Susannah Stark. The programme concluded with a series of live performances by a selection of the exhibiting artists.

Another frenetic force within the Belfast scene is Dawn Richardson. The owner of Framewerk art gallery and a cofounder of the queer arts space The 343, Richardson has continued to carry the DIY torch for Belfast, making unique art events happen within esoteric spaces across the city. These have included: a sound-art performance in a disused bank vault (I am Sitting in a Vault – which I created in collaboration with Constance Keane and Richard Bailie); a sound and music sleepover in the deconsecrated St. Martin’s Church; and an electronic music event in the slowly rusting Templemore Baths. Other spaces, such as Platform Arts and PS2 also play important roles. The regular programming of events like these within the city exemplifies Belfast’s continuing love affair with sounds emanating from the perimeters.

Sound-based art practices will surely only strengthen over time in Belfast. But what remains to be seen is whether these artists can sustain themselves within a locality that continues to have only tentative connections with the wider commercial and contemporary-art worlds. Even within Ireland, the sound-art scene remains relatively fragmented. For example, a vibrant sound-art scene exists in Cork, based around improvisation and performance, but such activity can often occur in isolation – unconnected to (and sometimes unaware of) activity in the north of the island.

Another major challenge for sound artists is the question of categorisation and how it is defined by different actors. Depending on context and circumstance, sound art can be encountered in music halls or galleries, as a performance or installation, as sound design or score. Because of this variability, the problem of how sound art should be defined remains a hotly contested issue.[6] This problem of definition has a number of implications, affecting not just how ‘sound artists’ choose to label themselves, but how they navigate support structures and funding opportunities, often falling between categories like ‘music’ and ‘visual art’ (or more granular delineations, depending on the institution). This problem is amplified by the rise of curators, as producers and custodians of dialogue surrounding categorisation; an issue that is a particular bug bearer for academics like Simon Waters, who views curators’ writings on sound art as ‘incomprehensible jargon’. Waters sees these curators’ attempts to contribute to the dialogue more as a way of hyping up their own ‘obscure position’ rather than elucidating and ‘communicating something quite profound’, in the way that writers did with movements like electroacoustic music and soundscape ecology. Until some clear form of discussion emerges around the discipline – and whether there ever will or should be (as Waters might also argue) – sound artists will continue to have difficulty articulating their work to less-knowledgeable audiences.

Returning to the analogy of the church bells, we can think of sound’s liquid and porous qualities as echoing the permeable boundaries of ‘sound art’ as discipline of study. Sound art transcends cartography, constantly shifting between the boundaries of neighbouring disciplines. There is an ongoing need for artists, who work with sound as a primary medium, to redefine their own territories, maintaining the space for progressive, interdisciplinary practices. This might be seen as a weakness of the discipline, but I would like to frame it rather as a weak strength. Speaking to practitioners like Shipsides, Waters, and Hamilton, I feel there is sense of hope that artists will persist in eschewing such clearly demarked definitions in favour of experimentation and artistic quality, both of which Belfast possesses in abundance. [7]

* This essay first appeared in PVA 11, which focused on music, and was published in 2019. More info on the printed journal can be found here.

Notes

[1] For a short introduction on the function of bells within European society, see David Garrioch, ‘Sounds of the City: The Soundscape of Early Modern European Towns’, Urban History 30, no. 1 (2003): 5–25.

[2] As well as having an established and respected practice, Mary McIntyre also runs an independent record label, TONN Recordings, which specialises in electronic synthwave music.

[3] Two former codirectors of Catalyst Arts have gone on to win the Turner Prize. The second was Duncan Campbell in 2014. Campbell, like Philipsz, also studied at University of Ulster’s Belfast School of Art.

[4] The general theme of House Taken Over and some of the works shown formed the basis for another exhibition titled Surveillé·e·s, which ran from 2018 to 2019 at Centre Culturel Irlandais (where Norah Hickey M’Sichili is director) and Solstice Arts Centre, Navan.

[5] The MA in Sonic Art was cut in 2015. This was part of a profit-saving initiative by QUB, which cancelled all MA programmes that were recruiting under twenty students per year. SARC now only offers a Masters of Research (MRes) course but a new MA course may become available in the future.

[6] For a good discussion on definitions of sound art, see Brian Kane, ‘Musicophobia, or Sound Art and the Demands of Art Theory’, Nonsite.org 8 (2010): 76–95.

[7] I would like to thank Helena Hamilton, Pablo Sanz, Daniel Shipsides, Paul Stapleton, and Simon Waters for their generously providing information and being interviewed as part of the research for this article. Thank you also to Joanne Laws for her editorial insights.