On 3 June 2014, in our first action as incoming Dublin-based editors of Paper Visual Art, we organised a talk at Temple Bar Gallery and Studios. Structured as an open debate, we asked participants to respond to the question, ‘What do you expect from art criticism?’ Four invited panellists spoke: artist-critic Jim Ricks, theatre critic and dramaturg Joanna Derkaczew, writer and researcher Rebecca O’Dwyer, and lecturer Declan Long. The discussion was moderated by visiting Art in the Contemporary World (ACW)/IMMA critic-in-residence Nuit Banai.

Long opened proceedings, focussing on the critic as an agent of resistance, bound up with, but potentially subverting, strict disciplinary divisions: a radical role for the critic of contemporary art. O’Dwyer echoed Long’s emphasis on multidisciplinarity, advocating an undogmatic criticism mindful of its own embeddedness and arguing against any sense of utilitarian ‘function’ for the critic. Derkaczew introduced, the idea of the critic as a ‘custodian’, with responsibility to maintain and foster audiences for the art form generally, as well as offering critique of its specific manifestations. Ricks concluded with a set of more radical proposals. He talked about the role of criticism in enabling or transforming citizenship, and called for more politicised, bolder and braver criticism.

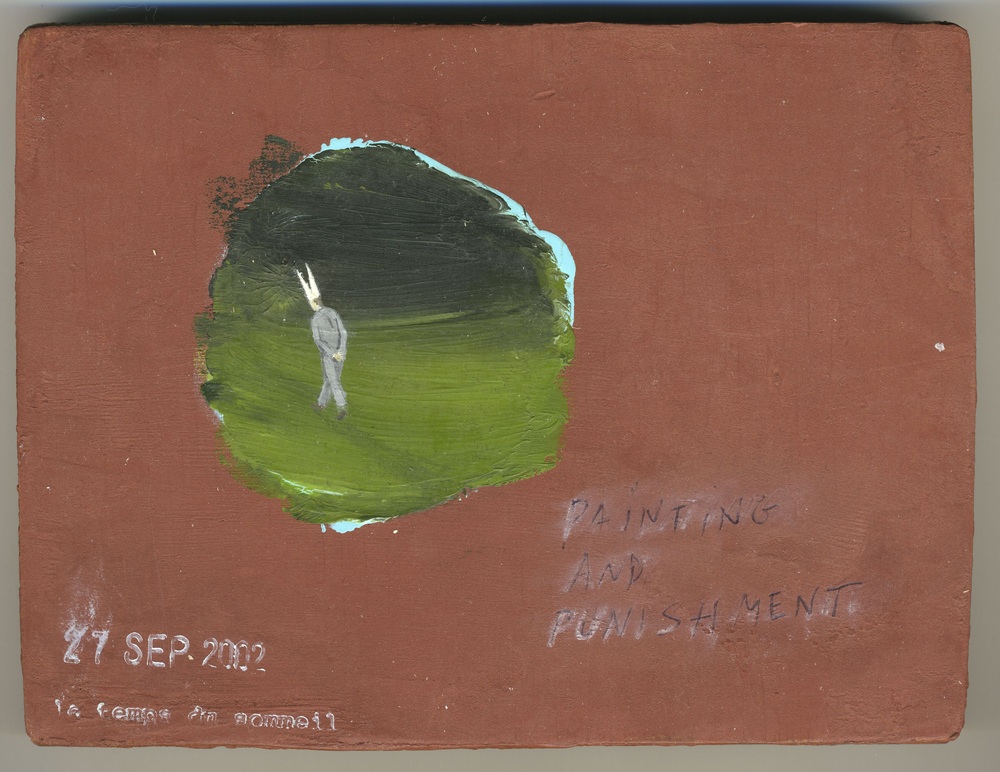

Left to right: Jim Ricks, Joanna Derkaczew, Rebecca O’Dwyer, Declan Long, and Nuit Banal.

Neither of us spoke formally, not wishing to prescribe or delimit the range of the conversation. Instead we treated the talk as a sort of consultation, ahead of the programme of collecting and editing material, which will be published over the coming months. So discussion was opened to the floor. Questions were asked about visibility and responsibility; about exposure and markets. Should the critic contextualise the art work in national or international contexts? Are the critical voices which speak through the national press compromised? Ultimately, what emerged from the discussion was a desire from all concerned for an ethical role for the art critic, be they working in a professional, semi-professional, or amateur capacity.

The impediments to this provision are well enough known not to need much reiteration. Faced with substantial budget cuts Circa then the only magazine of art criticism in Ireland, published its last print issue in 2010, and closed completely in 2011, leaving a major gap in the art-writing landscape. The subsequent lack of a robust art critical field is a serious and indisputable loss for the visual arts.

Despite this, there is no shortage of critical voices out there, no lack of dialogue about the functions and shortcomings and potential powers of the art critic: enough to make one suspect that this might be, in some ways, a good time to be writing art criticism in Ireland. This is an exciting, challenging time to be writing about art. There is a palpable – and open – sense of a struggle for its future.

What is missing from the current situation in Ireland is money. This is the real problem, the real ‘crisis’: we cannot pay our critics. Of the mass of art criticism produced in Ireland today, through online and print magazines, journals, blogs, only a fraction is paid. This is a considerable obstacle, and one from which PVA is not exempt. But the fact is, we need criticism to make the case for its own support. We need writing that engages with the visual arts. We need arguments against the instrumentalism of twenty-first century economic policy. As art critics we need to find new criteria – the bases of new ethical or civic value systems – and we will only do so through critical exchange. Over the coming months we will publish reviews and essays, demonstrating by example the value of serious criticism.

What will this serious ethical criticism look like? This is not an easy question to answer. But we believe one route out of the present sense of permanent ‘crisis’ is through the voice. Not a singular proscriptive voice – not the voice of the Victorian belletrist or the modernist pontificator – but a voice that is varied and textured and specific. This voice need not necessarily embody an ‘opinion’. One opinion is both too easy and too narrow. Each piece of writing can, on the contrary, reinvent the voice. The critic can invite disagreement and discord into their deliberation; the critic can host a dialogue in one voice. This is the virtue of the voice, as we see it. It belongs, it has a position. It is constituted by its context. This is also its shortcoming.

And it is precisely through this shortcoming that we believe the real value of the critic will emerge. The critic, if he or she is to be an ethical critic, will have to be relentlessly responsible. To begin with, the critic might aim for the specific. Speaking in generalities too often enables a writer to gloss over the intricate entanglements of the art world, not just the individual art work, but its funding base, its genealogies, and the institutions that support and make it visible. The critic will also have to be honest about their own position within the hierarchies of the art world: they will have to examine and reveal their own interestedness, their own privileges, their own biases. They will have to be aware of the power of every single utterance, and will have to accept the burden of it. The critic will most likely speak from a position of privilege. What great criticism will do is use this privilege to articulate difficult positions and take responsibility for the things it describes.

Great criticism will also need to be supported. The critic’s role – not as an arbiter but as an interrogator of values – is one which we must value in return. The argument must be made for supporting criticism. It is one of the aims of PVA to mount this argument. The other is to implement it, by publishing criticism and writing of a high standard, which says something meaningful about the arts in Ireland, in a way that is relevant to a readership (be it specialised or general or – as is more common – something in between), and with a reach that enables the preoccupations of our localised art world to connect with wider international debates about the nature and function and value of the visual arts in the twenty-first century. This is admittedly a tall order. But they are tall orders with which we are presented.

– Marysia Wieckiewicz-Carroll and Nathan O’Donnell