Richard Mosse’s seductive, problematic, and much discussed The Enclave made its second appearance in Ireland in late March as part of the 2014 Irish City of Culture in Limerick city. The Enclave is a photographic and film-installation work shot in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and was first shown at the 55th Venice Biennale last year as Ireland’s representation, curated / commissioned by Anna O’Sullivan. Such are the physical requirements of the work that two separate venues were used in Limerick: Ormston House and the nearby 6A Rutland street.

Richard Mosse

Beaucoups of Blues

North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012

Digital C-Print, 183 x 229 cm

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

I saw the large, sumptuous photographic prints during the opening event on the Friday evening and the film-installation on the following Saturday morning. The four selected framed, photographic prints on show are incredible landscape shots. The strange beauty of this Congolese terrain is made more conspicuous by the extraordinary pink-colour palette where otherwise one might expect to see shades of green. The format employed by Mosse is the obsolescent Arriflex infrared film, once used in reconnaissance missions by the US Airforce in the 1960s to help distinguish and uncover actual vegetation from camouflage, the real from the imaginary, the non-threatening from the potentially potent. It is a format that has been used before in a visual art context, but it forms the absolute aesthetic centre of how Mosse relays to us his interaction with this conflict. Everything that we are shown is imbued with this colour.[1]

I have not been to the Democratic Republic of Congo and have little knowledge of this specific conflict that has waged since 1998, claiming over five million lives. And weirdly, this work does not spark any further curiosity in me to learn more about the conflict itself. The political and social features of the conflict here are rendered incidental to the more important business of how the place and people of the conflict might be aestheticised.

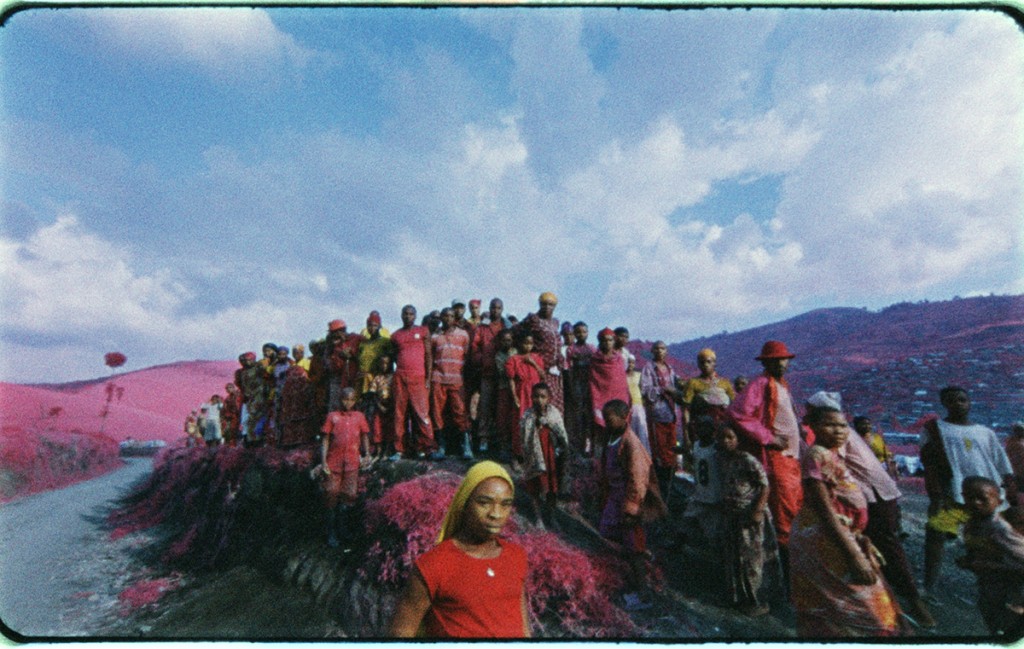

Richard Mosse

The Enclave

2013

16 mm film stills

Six screen film-installation

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

The film-installation in Ormston House is on a smaller scale compared to how it was shown in the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), Dublin, earlier this year and in Venice last year. It was my first time to see this work—it was an astonishing visual and physical experience. It is an excellent and seamless installation with six two-way screens arranged in the gallery that invite the viewer to navigate the space. Hung from the ceiling in the otherwise completely darkened gallery, the fragmented, non-narrative HD video works are projected onto these screens in thirty-nine-minute cycles.[2] The visuals show rural scenes that move from initiation rituals of soldiers and militia men and women, to hammy re-enactments of murderous clashes, skirmishes and scuffles, to still landscape shots with serene lakeside views, to an extraordinary sequence in a packed, colourful small-town hall where youthful performers on stage jump through a flaming hoop and perform incredible athletic reverse somersaults. In this town hall sequence a sharply-dressed band plays too, and near the end of the sequence, some ladies appear to model themselves in a cool, ambiguous way for the onlooking military hard men who gaze ambivalently from a separate table on the same stage. All throughout we can see in view other photographers frenetically documenting this seemingly playful event.

Some of the other sequences in the film-installation are coordinated with each other, sometimes on two or three screens at once. In one sequence we are brought along a country road on a van. In another, there is a low view of the side of a river; militia men fire or appear to fire at some unknown Other in the undergrowth on the opposite bank. The river water gushes voluminously past.

These scenes are interspersed with a smooth shot that brings us up a country road, passed a bloodless, prone corpse. It is an inquisitive and solemn scene, but I half expected this body to spring to life; to walk back up the road in the dusty heat. These sequences and the way in which the work is installed inter-subsumes the cinematic with the sculptural and the theatrical.

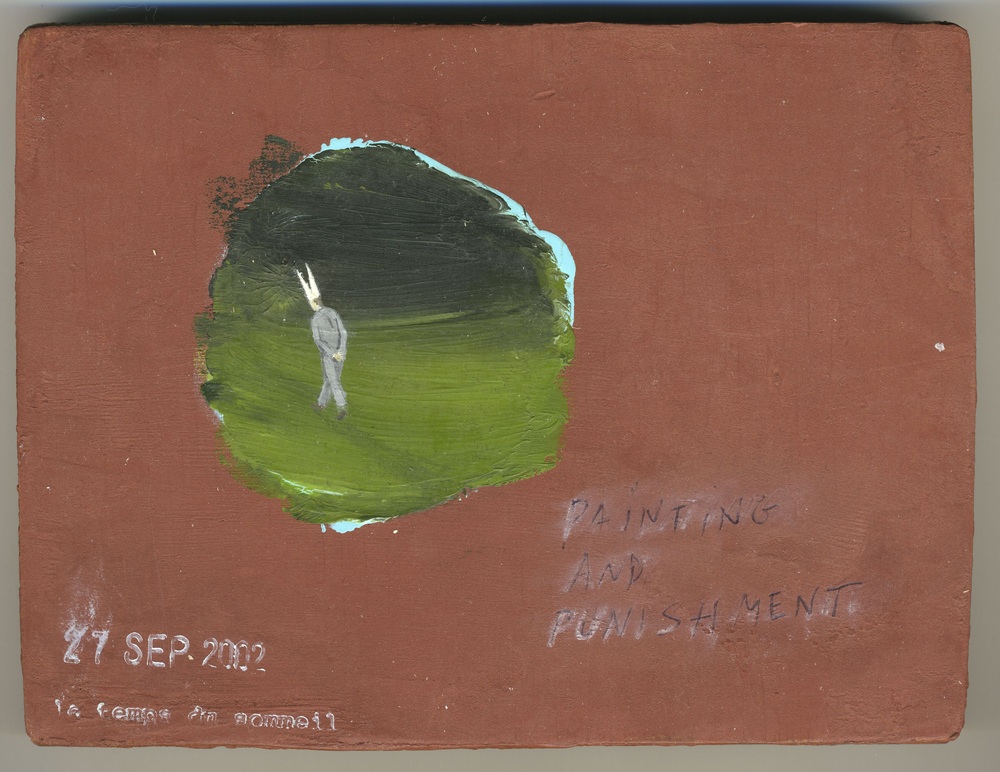

Richard Mosse

Platon

North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012

Digital C-Print, AP, 183 x 229 cm

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

The work is incredibly well filmed by American cinematographer (and sculptor) Trevor Tweeten, who has previously collaborated with Mosse. Ben Frost, the sound recorder and sound editor creates an effective and at times dissonant score / soundscape composed of field recordings. I saw Frost playing live a number of years ago in Whelan’s in Dublin, where he generated an almost insurmountable wall of sound—to the point that I could feel the soundwaves from the vast array of speakers behind him on stage reverberate through my whole body. These three artists work very well together; they are skillful, successful, and ambitious young men.

*

In a non-narrative work, the filmmaker can sidestep constructs of traditional storytelling, whether this storytelling is fiction, memoir, reportage or documentary, etc. However, the smaller sequences in this supposed non-narrative contain micro-narratives in themselves, and these smaller narratives give a sense back outward as to the nature of the diffracted, larger whole. The cumulative repercussions of these smaller narratives create a larger effect. And effect is what Mosse is most assuredly going for here to the point that it compresses the human subjects that seem merely to happen to appear in the footage.

One film sequence that at once blew me away but also destroyed something of my interaction with this artwork shows a mother giving birth in the soft, dark-blue gloam of a cramped operating theatre. The pink filter continues to thwart / heighten the footage. This edited sequence has a recognisable dramatic narrative: child emerges from woman, child struggles for its first breath, child comes to life. It is shown on one screen while on another on the far side of the gallery we are being shown dead bodies. This is a too easily earned and clichéd visual relation. It reduces both incidents to just visual manipulations. But what is most troubling about the operating theatre sequence is that after we see the infant being pumped into life, like a set of bellows, we then cut back to the mother again, lying splayed, exhausted, and open-eyed with white sterilising strips being applied to her lower abdominal areas. It is at once explicit, seemingly frank, and ironically coy—it flattens this subject, this woman, and razes this film enterprise of its moral complexity. It is a strange moment of brilliant manipulation—but a type of brilliance that I am not drawn to. At this moment I am brought from the position of rooting for this dark blue-green and barely breathing newborn, to a moment where the narrative is taken suddenly, jarringly, into an academic conversation about photography, dissemination, display, and the plane and frame of the shown image. The human, this woman and I, are alienated. We are both powerless in the face of the mediation, only I am looking on at her lying there in splayed inertia. She is being advertised to me. Our cultural and ethnical distinctions are hollowly rehearsed. The moving image pretends to go ‘too far’, but it doesn’t go far enough, because I am being told a banality: that this woman is not a white Western person. But what is problematic is that this banality is felt to be made explicit here and now in such a traditional and uncritically Orientalist way. The amplified visual has merely replaced the textual. My ignorance of these individuals and of this greater situation is not altered in a way that might belong to them—my ignorance of this place and people merely becomes more refined and complex.[3] The fact that this is manipulated footage ceases to matter; the editor and producer’s choices fall emphatically into the service of creating an asymmetrically spectacular event.

Richard Mosse

The Enclave

2013

16 mm film stills

Six screen film-installation

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

There was one other sequence that appears in the middle of this superbly-designed cacophony that shows footage of a smooth descent down a hill, through a parted crowd of gaping onlookers, passed a series of huts and tents into an enormous sprawling ad-hoc camp, as kids playfully run in criss-cross at the foreground while glancing back at the camera as they go, until we slow, stop, and settle on a man—sitting outside the opened door flap to his tent—holding an infant wrapped in a blanket. The camera stares. The man, the father, this prop looks up and gestures vaguely toward the child’s face with a frayed edge of the cloth. The camera continues to stare, intruding not only on the personal space and time of the subjects, but also on ours. The darkest heart of our curiosity is again aimlessly illustrated to us. It is a brazenly pre-planned staging presented as improvisation. It is remarkable. Then the camera pulls up, away, and we are given a brief, high-definition glimpse of the appearance of a film reel being uncoupled from its mechanism.

Adrian Duncan is an artist and writer based in Berlin.

_________________

[1] Claudia Andujar, a Swiss photojournalist, used the Arriflex format in the mid-1970s.

[2] The original filming was done in 16 mm film, then transferred to digitial high definition (HD) for editing, dissemination, and presentation purposes.

[3] Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Routledge, 1978).