The Highlanes Gallery in Drogheda, a former Franciscan Friary Church built in 1829, is a fitting location for Things in Translation, a Drogheda Arts Festival commission curated by Helen Horgan and Aoife Ruane. Established in 2009 by Horgan and Danyel Ferrari, the LFTT library or The Legs Foundation for the Translation of Things is an art collective and moving library project. The two artists were offered a collection of four thousand books following their residency at the Multyfarnham Franciscan Friary (the friary and library were undergoing structural changes at the time). For Things in Translation, eight artists were invited to create new work using the former Franciscan library and archive as raw material or source and included: Vivienne Byrne, Aoife Desmond, Ferrari, Jessica Foley, Horgan, Áine Ivers, Susan MacWilliam, and Méadhbh O’Connor. The result is, for the most part, an engaging show that revealed the diversity and endless possibility found within a collection of books, books whose subject matter belong to philosophy, poetry, fiction, architecture, history, theology, poetry, etc. Some artists chose a number of books to respond to while others lingered on one.

The LFTT Library

2013

Installation view

Courtesy the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

Vivienne Byrne’s two-part The Merging Point is a projection on the gallery wall and a smaller video installation in the library. The first titled The Splitting Point is a large video projection in the main gallery that shows the Inver Colpa rowing club training on the River Boyne in preparation for a journey from Drogheda to the Isle of Man on 21 June, 2013. Two overlapping circles, one smaller than the other, offer two viewpoints of the river. The outer circle seems to be a view of the surface; it is slower, sometimes stationary. A reflection of a bridge or a town line can be seen silhouetted on the water’s surface. The inner circle disappears and reappears—the water is frantic and quick. A rhythmic sound of oars through splashing water can be heard, and at times, the tip of the rowboat appears, wrestling with the water as it pushes onward. This projected oculus seems to tunnel through the surface of the gallery wall to form an uneasy and limited view of the river and landscape. It is swirling and all consuming, and we, as viewers, are taken on this journey too.

Things in Translation

2013

Installation view

Courtesy the artists and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

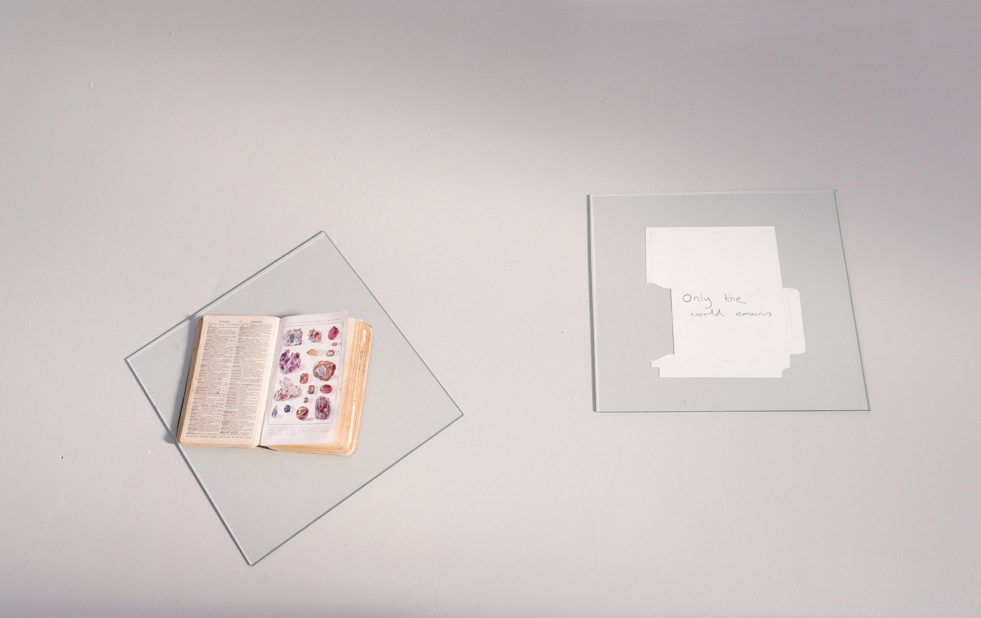

To the right, Aoife Desmond’s installation Only the world remains is an installation of painting, objects, and books. On the floor, a small English dictionary is open on a square sheet of glass and beside is the underside of chocolate packaging with the words “Only the world remains” scrawled in pencil and placed under a square piece of glass. The left page of the dictionary lists words from infernality to infusorial, and the right page contains detailed drawings of precious stones and gems such as emerald, ruby, peridot, amethyst, and citrine (quartz). On the adjacent wall hangs a large sheet of reflective foil card with a number of small images of rare gems painted in watercolour, similar to those illustrations found in the dictionary. To the right are more paintings of gems but on torn and frayed pieces of silver foil wrappers, hung loosely, and framed by the reflection of light onto a large mirror that is propped up by a chair: they shimmer and glisten, bringing to life the rare gems that are painted on each metallic surface. Redrawn and reflected, there is a sense that Desmond is retelling some story or history, unearthing objects often overlooked or thrown away. Just like the words found in the dictionary on the ground—infuse, influx, inflatus, influence—there is a sense of things seeping, of flowing and merging together, of transforming infinitely from one thing to the next.

Aoife Desmond

Only the world remains

2013

Glass, chocolate packaging, pencil, dictionary

Courtesy the artist and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

Susan MacWilliam’s work Where are the Dead? includes six framed ink jet prints of open book pages and a neon light installation. The book being used here, written in 1928, is a collection of essays written in response to a letter published in the Daily News, a London-based newspaper that asked for answers to the question of life after death. Novelists, writers, scientists, churchmen, theologists, etc., responded to the question, offering a range of views. But MacWilliams doesn’t present these responses or give the viewer any answers: only the title and verso pages of the front and back of the book are displayed. The question is repeated, put back on the viewer in the gaseous glow of the curving neon tubing to the right: “where are the dead?,” it asks again. A hollow question, and one that itself will disappear and dissolve when the electricity is switched off. MacWilliam’s work has long dealt with questions of paranormal activity, with vision and perception. Her work investigates the history of parapsychology and psychical research, often focusing on the objects used by materialisation mediums such as apparatuses for communication or experimentation, books and Victorian spirit photographs, or the ectoplasm produced during séances—the white, oozy, cloth-like ghostly residue. In a previous video work titled Dermo Optics (2006), the artist ventured to Paris in 2005 to document paranormal experiments at the Centre de l’Information de Couleur by its director, Dr Yvonne Duplessis. Here, they researched Dermo-Optical Perception (also known as eyeless sight, skin reading, or fingertip vision), the ability to perceive text or colour without the use of eyes. MacWilliams reduced the ninety-minutes of film footage to a fast-paced four minutes and nine seconds. In a similar way, the empty pages of Where are the dead?, with the reduction of frames, the removal of potential evidence or truth puts it back on the viewer to fill in the rest, to create something from the absence and make sense of it.

Susan MacWilliam

Where are the dead?

2013

Framed ink jet prints

Courtesy the artist and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

In the centre of the gallery is Méadhbh O’Connor’s Give me a place to stand, with a lever long enough, and I can move the earth. It is an installation constructed with found objects: a fallen tree, rocks, moss. A large rock is attached to the tree by a coil of green moss. It is suspended, held in place by a second rock, and balanced. This assemblage forces these natural forms to perform: it is unnatural, imposed, and acted upon. The title is from a quote taken from Archimedes’s Law of the Lever that nods towards past scientific achievement and discovery—a history that reveals the manipulation of the environment to further our own understanding.[1] Hung on the wall behind is Evergreen, a large photographic print of a radio mast posing as a tree. It stands in the centre as if the lone survivor of some natural disaster. The image has a strange purple hue that further unveils its trickery and deceit—it is not what it purports to be. O’Connor references the book The Romance of Water Power by Paul Lewis, written in 1931, which details the function and possibility of hydroelectric power. Here, the environment and its ‘use’ is to serve mankind above anything else.

Méadhbh O’Connor

Give me a place to stand, with a lever long enough, and I can move the earth

2013

Installation view

Courtesy the artist and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

Áine Ivers’s The Hunt presents a large watercolour hung on the wall and a number of books taken from the library that seem to draw on religion, mysticism, human anatomy, and so on, placed on a table. Ivers prompts the viewer to navigate through these pages of illustrations and text, but also controls how this is done. Each book is open and held in place by a piece of string and by doing so, she limits the viewing; our desire to turn the page is restricted. A small handmade book made is also included in the collection, but unlike the other books, we are able to read through the bound tracing paper covered in small, neat handwriting. The narrative—at times verbose and needlessly enigmatic—reveals a story about a hunt for the ‘Grillos’, this lover/tormentor who the narrator is in search of.

In front of the large altar is Helen Horgan’s Hermes Alive!. Made of plywood, mild steel, and felt the structure is shaped like a lyre, an early instrument used in classic Greek antiquity. The steel ‘strings’, however, extend outward to form the shape of a tortoise shell. Placed in front of the decorative altar, the object appears almost sacred. The viewer is invited to interact with the sculpture, placing both hands in the two holes at the top of the instrument and head through the primary crossbar. In the artist’s statement, the tortoise shell refers to a movable shelter or vaulted arch, and it was from this patterned shell that gothic architecture found its supposed beginnings. At the same time, the object doesn’t take itself too seriously—it is an oversized, ballooned caricature of itself. I am reminded of carnivals or fun fairs feeling exposed and slightly embarrassed as I place my hands and head as instructed through the holes hoping that no one enters the gallery. Horgan presents a number of different narratives that overlap and infuse into a single material form. The viewer too may participate in the object’s transformation, into something playful or even sinister. It also brings to mind stocks used for punishment in medieval times, an object of humiliation and cruelty. Horgan’s object transforms, becoming not one thing but many.

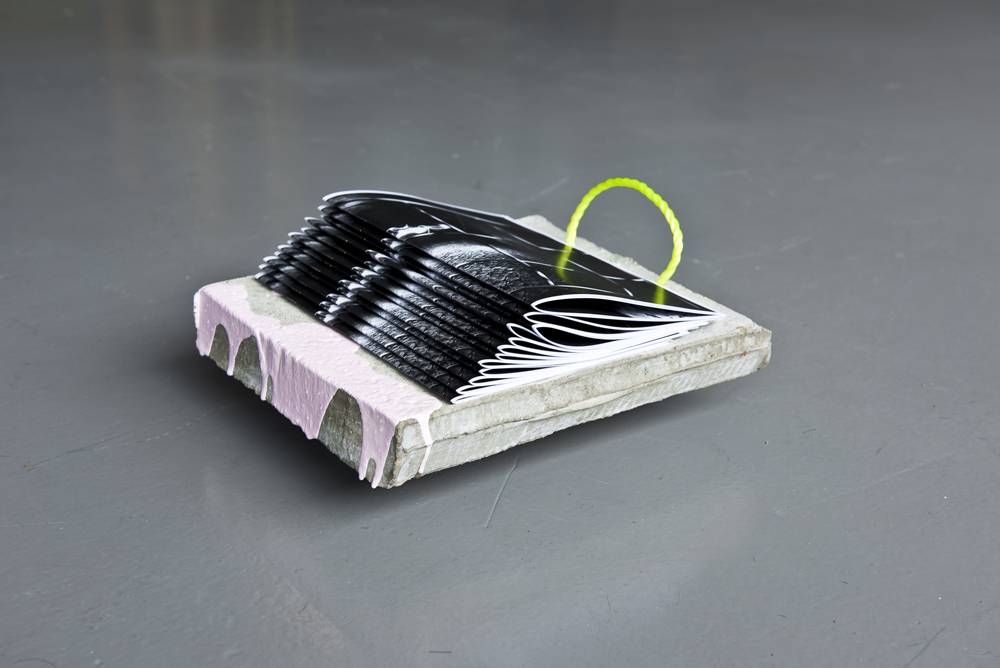

Danyel Ferrari

Unreadymade

2013

Live-feed video installation

Courtesy the artist and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

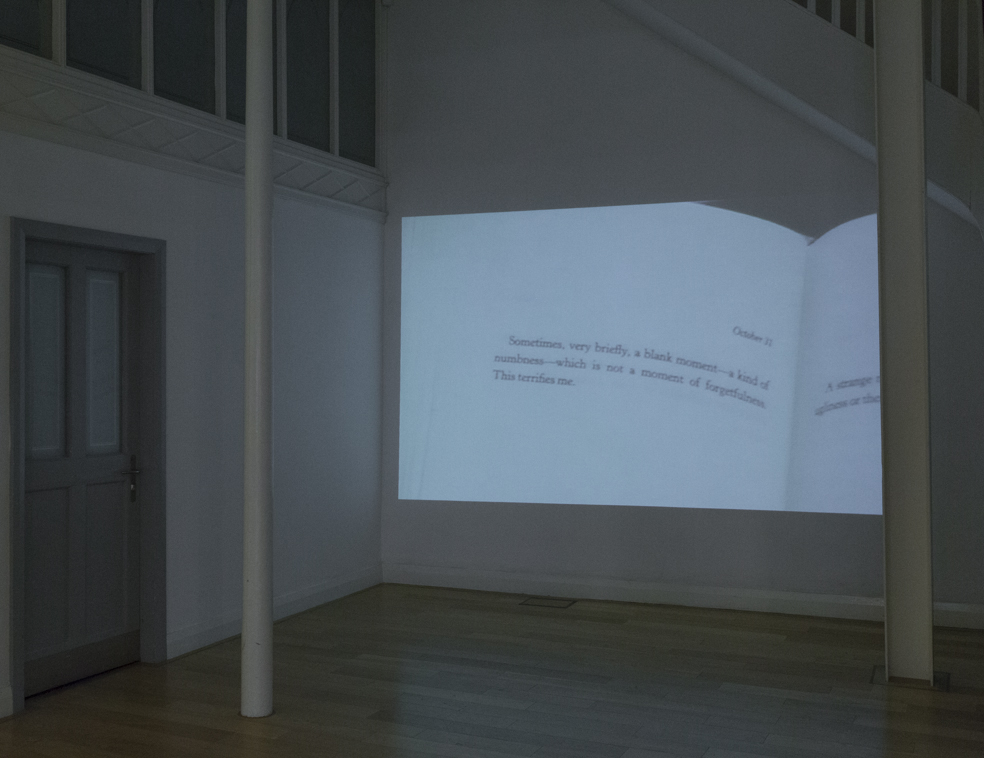

Danyel Ferrari’s Unreadymade is a live-feed video and installation that draws on Roland Barthes’s Mourning Diary, a collection of thoughts and observations that was published following Barthes’s own death. After his mother’s death on 25 October, 1977, Barthes began to keep a diary of his suffering and grief, written mostly in ink on small individual slips of paper. Ferrari’s live-feed video shows pages of the diary moving back and forth—the dated entries are allusive and difficult to read. In the stairwell on the first floor Ferrari has installed the book, suspended in the air by four pieces of string. Two fans, one large and one small, are directed toward the book causing the pages to move and flicker. It is out of reach for the viewer at both levels—in abstract and physical form. The feeling of mourning is erratic and chaotic, but also translated and remembered in the pages of the book. In the live feed projection in the main gallery, one entry dated 31 October (the only page I can discern) reads: “Sometimes, very briefly, a blank moment—a kind of forgetfulness. This terrifies me.”

In the far corner of the gallery beside the altar, the LFTT library is installed. The softly lit space is warm and inviting. On the adjacent wall a piece of card is hung, listing unusual categories (e.g., hideous books, books on thinking, books the cat likes, beautiful illustrations, nice bindings, etc.). Each description corresponds to a sticker found on the spine of most of the books in the library. Among these shelves of books, is Jessica Foley’s thoughtful and engaging “found-object installation.” In the corner of the library beside a red armchair, a live recording of the play Elsie’s Counter can be heard. The play, recorded in the gallery during the run of the exhibition, is based on two libraries: the LFTT Library and the lending library owned by Foley’s grandparents in Artane during the 1950s. The play was recorded with professional actors and the ‘Foley artist chorus’ (who provided the sound effects) before being transferred to vinyl. The turning, crackling record speaks of a time gone by, of radio broadcasts, and analogue. The play has three characters: Harri, an academic with an interest in libraries; Elsie who runs the lending library; and William, the now deceased husband of Elsie.

Jessica Foley’s Elsie’s Counter (background), Helen Horgan Hermes Alive! (foreground)

2013

Installation view

Courtesy the artists and the Highlanes Gallery

Photo: Eugene Langan

Harri: It’s your husband’s library? Isn’t it? His name appears a lot … in the lending tables?

Elsie: It was, in the end. He died last year.

Harri: Oh. I’m sorry for your loss.

Elsie: It wasn’t so much a loss, Harri, as a wearing away. He sort of disappeared on me … into that library. (Her voice trails off) Did you get a sense of him, while you were packing earlier, by any chance?

For Elsie the library became a burden, a weight following the death of William. The chairs and copper-top table (similar to that found in the Foley’s lending library) placed just outside of the library space seem to also reflect this burden. Each leg is placed on a stack of books and bound securely with twine. The heaviness of the objects reveals a sense of loss and ruin. It is almost as if the collection of decaying objects themselves are speaking, as if the layers of history are being reimagined and preserved. The collection then can be seen as an extension of the self: owned and possessed by the reader, they are reflexive of a character or personality. As Walter Benjamin said about his own collection of books: “Ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects. Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.” [2]

Niamh Dunphy lives and works in Berlin.

____________________________________

[1] Regarded as on of the leading scientists in classical antiquity, Archimedes (c. BC 287–c. BC 212) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer. His work titled On the Equilibrium of Planes studies the Law of the Lever: how small forces can move great weights by means of the lever, and the balance of weights along the length of a lever.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my Library,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovlch, Inc., 1968), 67.