The urban environment is anything but a static place. The fluctuations affecting the politics, economy, technology, and culture not only pull people into urban centres, but also forces them out. Moreover, the influence of such changes tends to be broad. Not only do they affect the physical and spatial character of the surroundings, they also play a role in what people notice and the ways in which they interact. Seeing the city as a continuously modulating weave that subsumes the enduring and the ephemeral, the remarkable and insignificant, the familiar and strange produces a fascinating impression of a place that can never be fully comprehended; that can only be experienced in fragments and always offers something more to see. It is this process of the city’s ongoing transformation and sense of incompleteness that imbued an invigorating pair of exhibitions this summer. These shows, which ran concurrently and took vastly different approaches to exploring the city through art, grabbed my attention for the way they focused on the overlooked and under-represented, as well as the haphazard and unforgiving qualities of city life.

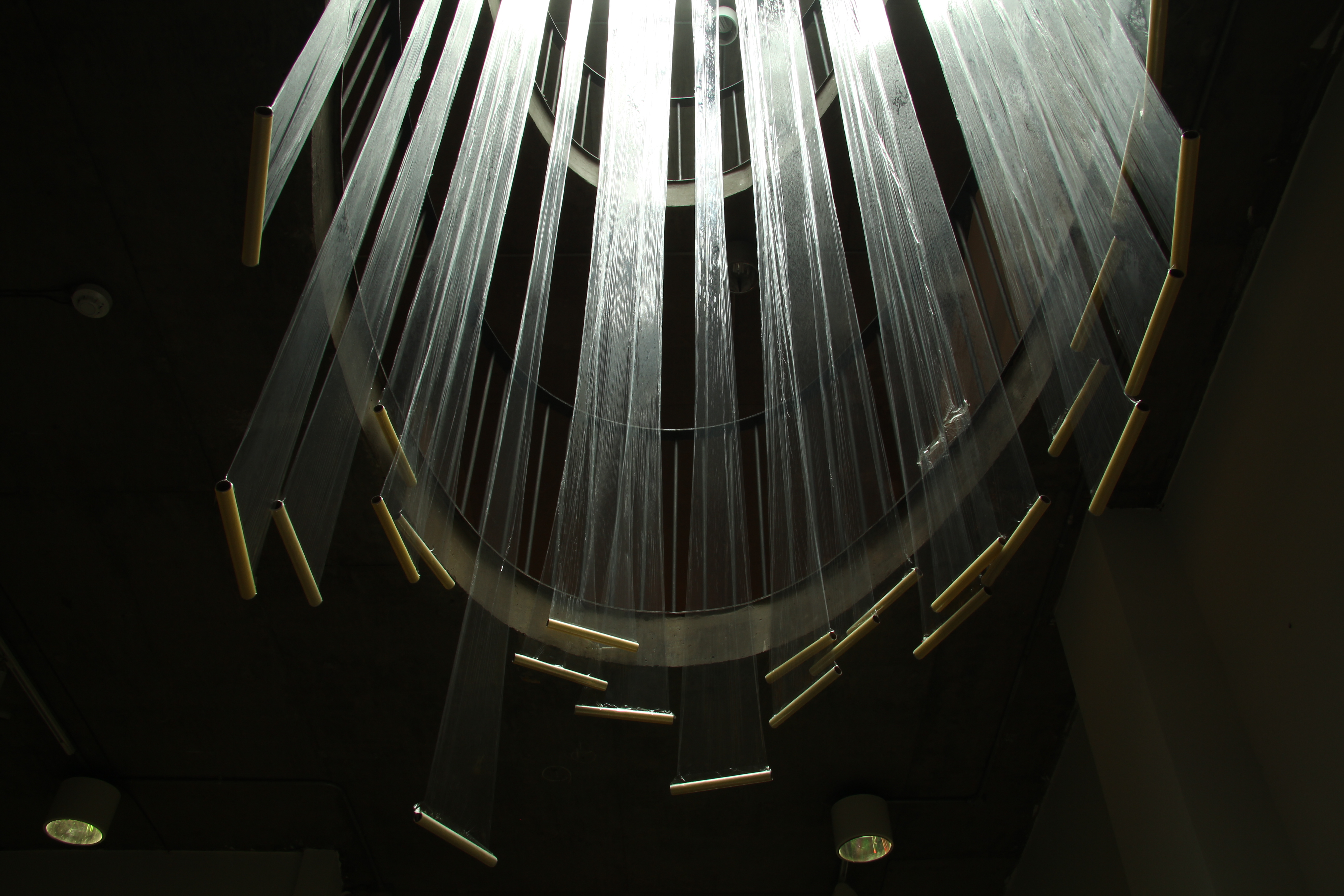

Laragh Pittman

Museum of the Re-Found

2013

Installation detail

Photo: John Gayer

In Museum of the Re-Found, which derives from collaboration between the artist and the Lantern Centre’s International Women’s Group, Laragh Pittman presented a makeshift museum replete with reading room and children’s play area. The artifacts in the collection relate to a series of exploratory journeys the group made to Dublin City Hall, tenement buildings on Henrietta Street, the Iveagh Gardens, the Irish Jewish Museum, and various other locations. It consists of documentation—personal notes, diagrams, stencils, plaster casts, and fold out books made by the participants—as well as photographs, maps, and books they compiled that hold examples of marquetry, ceramic tile, carved wood, and fabric design. Supplementary material includes digital images of hand-tooled leather book covers from the Guinness family’s recent donation to Archbishop Marsh’s Library and several casts of decorative ironwork produced by sculptor Ulrike Holmkvist. Not only is the emphasis of the collection on craftsmanship and architecture-related technologies, it also emphasises the importance of colour, pattern, and ornament, as well as the influence of Classical, Medieval, and Eastern styles in Dublin’s built heritage. As such, the exhibition shows that the city has been and continues to be a conduit for people from various lands. This point is brought home by an informational note that accompanied the images of the leather book covers. It stated that many of the bookbinding workshops were located in the Liberties area and that many of the craftsmen came from families who had migrated to Ireland. Moreover, the International Women’s Group, whose members hail from Ireland, other parts of Europe, Africa, South America, Asia, and the Middle East underscore this fact. And their response—a new map of Dublin—forms the other major component of the presentation.

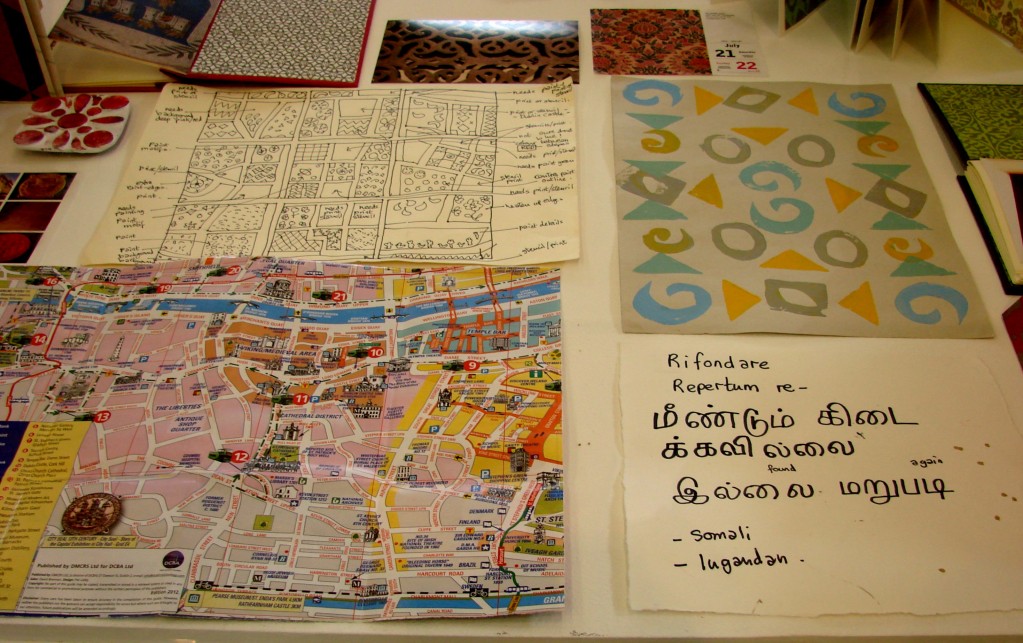

Laragh Pittman

Museum of the Re-Found

A new map for the city

2013

Courtesy the artist.

The map has been painted onto a grid made up of nine low-level tables whose arrangement allows viewers to literally walk around and through the city’s core. The areas delimited by Dublin’s streets have also been transformed into hyper-vivid polygons filled with abstract patterns and versions of the designs encountered on the group’s outings. The map proposes an amalgamation of the fanciful and real and comments as much on the ways people might envision a city, as on the ways that city can evolve. It, for example, represents St. Stephen’s Green as a micro version of the map itself in which the park’s verdant appeal has been reduced to a green abstract floral motif set within a nine-square grid. Moreover, not all of the names on the map seem familiar. The fact that there is a waterway called ‘El Gran Canal’, some street names have been translated into Tamil or Hebrew, and Cork Street has been replaced with ‘Somalia Way’, speaks about the changing face of urban neighbourhoods.

Laragh Pittman

Museum of the Re-Found

2013

Stencil (St Patrick’s Cathedral)

Courtesy the artist.

Pittman, in speaking about the museum, noted how the project comments on various historical precedents and changed most of the women’s impressions of life in the West. Their response, with its focus on design and craftsmanship, also represents a form of unity that—like music—operates as a universal language. For viewers visiting the museum, the experience proved fascinating as it (re)acquainted them with aspects of Dublin they had forgotten or had not even been aware. Moreover, exploring the vibrantly hued, alternative representation of Dublin took visitors on a parallel adventure that also allowed them to share in the newcomers’ sense of excitement and discovery.

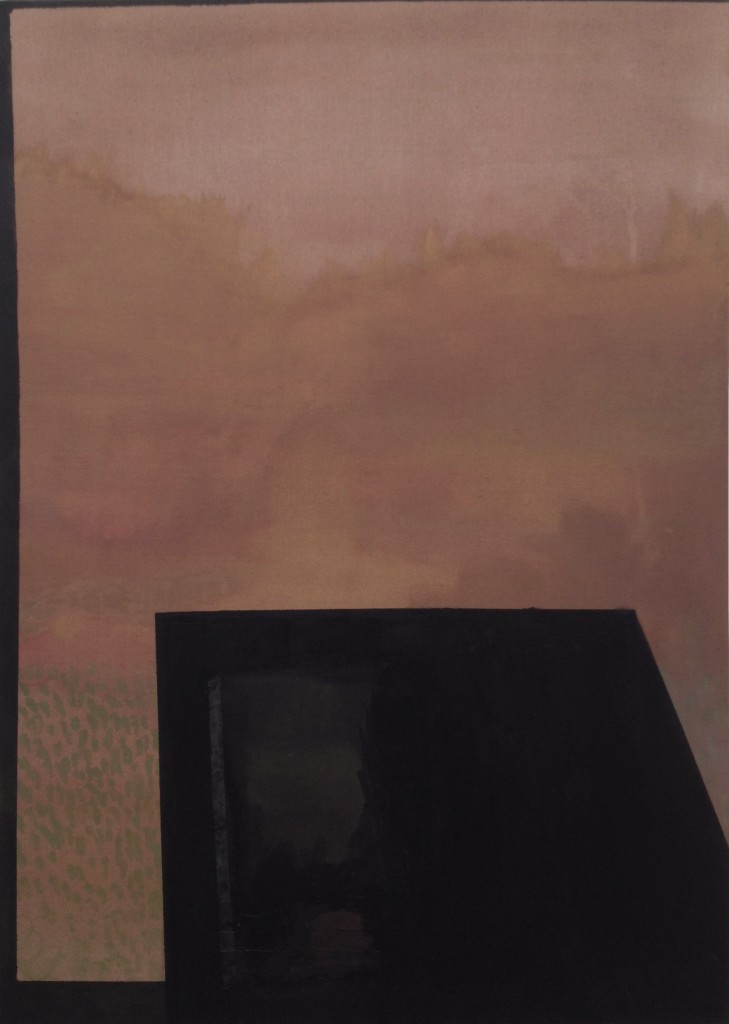

Ramon Kassam

Inserted Tape Posing As a Nude

2013

Acrylic and tape on canvas

152 cm x 152 cm

Courtesy the artist and PP/S.

The process of viewing Ramon Kassam’s work could also be likened to a voyage, albeit one that proposes travel through the familiar territory of painting. Depicting a world of hints and suggestions fabricated out of sporadic paint doodles, collaged fragments, re-stretched canvas, and abutted canvases these paintings set the mind abuzz with thoughts and questions. At first glance they come across as haphazard constructions—painting by way of accident and the production of deliberately off-kilter compositions—that make little sense. Then, as pictorial elements coalesce into figures or spatial arrangements, scenarios emerge. For example, it could be argued that Embedded paper tells me you’re awake intimates a figure ensconced in bedclothes, and then again the opposite also seems to be true. Couple argue over rotating painting excels at conveying emotion. Not only does it depict the back-and-forth movement (or statements) of a ghostly couple along with the unusual subject of their quarrel, it also evokes the resounding awkwardness felt by the onlooker who, out of happenstance, had to witness that quarrel. Feeling also underscores the sublimely colourful Eyeing drawings taped to a window with a great Limerick sky. Here the artist links himself directly to his environment by twinning atmospheric turbulence with inner unrest. And coy humour surfaces in the re-deployment of a paint-stained length of masking tape in the still life Inserted tape posing as a nude.

Ramon Kassam

Incomplete plein air waiting in the dark

2013

Acrylic, paper, tape, tacks on canvas

101 cm x 142 cm

Courtesy the artist and PP/S.

Ramon Kassam

Portrait cuts itself out on the floor

2013

Acrylic on canvas

67 cm x 71 cm

Courtesy the artist and PP/S.

In the text accompanying the exhibition, Michele Horrigan notes that Kassam likens the attributes of city living with all of the things that compete for visual attention and the proximities it precipitates, to “physically living within a painting…” Indeed, his idiosyncratic images delineate odd perspectives and chance encounters that, because of their fractional and fleeting nature, stymie clarification. For many of us, such episodes hold no significance, but I imagine them inuring Kassam’s mindset. He sees the ruminative potential of such glimpses and successfully melds their bewildering qualities into his work. In response, the eyes are forced to criss-cross the surfaces of the paintings to sort out the elements’ relationship and determine the images’ potential meanings. Though Horrigan finds the bewildering qualities of the work to be eerie, and even menacing, I see them as bites of reality—hard-nosed compositions referencing bleak situations, that evoke day-to-day discord, and never play up to the viewer. Like Pittman’s museum, Kassam’s works are ebullient. Though muted, his palette is full of subtleties and just as richly varied. Despite being static, his canvases communicate the paradoxes associated with transitory phenomena to reveal things we easily miss or choose not to notice. The alternate perspectives they offer urge us to look and keep looking, as well as re-evaluate that which surrounds us.

John Gayer is a writer and artist currently based in Helsinki, Finland.