Transference, curated by Cliona Harmey and Clíodhna Shaffrey, took place in Monstertruck Gallery in Temple Bar and Broadstone Studios on Harcourt Terrace. The exhibition was made up of selected artists from the Black Church Print Studio whose backgrounds are predominantly printmaking; it proved to be a cohesive annual show.

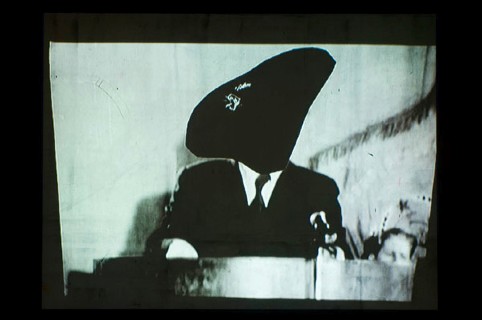

Catriona Leahy: Reverberation

video projection, looped with sound

dimensions variable, 2011

Photo: Paul McCarthy.

The title of the exhibition is entirely fitting as this method of working is entangled in every fragment of the artwork. There is a sense that an act of ‘transference’ is ongoing. Firstly, the fact that the exhibition takes place in two venues allows for the implication of one upon the other. Secondly, the selected works do carry a particular resonance with each other and imply a conversational note to the viewer. Thirdly, the majority of the works are not prints, reflective of how the discipline and rigor of printmaking might transfer into different media.

Monstertruck Gallery

I visited Monstertruck Gallery first, taking my cue from the order in which the exhibitions opened. Elaine Leader’s installation Untitled (2011) comprised of a roller shutter door and four 2,000 watt lights. When the viewer walks in front of the doors, a sensor triggers them to curl upwards at high speed, and from inside, the lights glare at you. You are literally caught in headlights, trapped, stunned and exposed at once. In this gallery space where your role is as a viewer, you are blinded. Catriona Leahy’s projection of an empty handball alley, with two birds perched side by side atop the center wall evokes an entirely different reaction. The stillness of the shot contrasts with the confused patting of the ball. The birds seem to act as narrators, their heads bobbing in conversation. They become a vehicle for nostalgia and observation of the brevity of occupancy and use. The video appears as a lament for something lost, a reenactment of sorts.

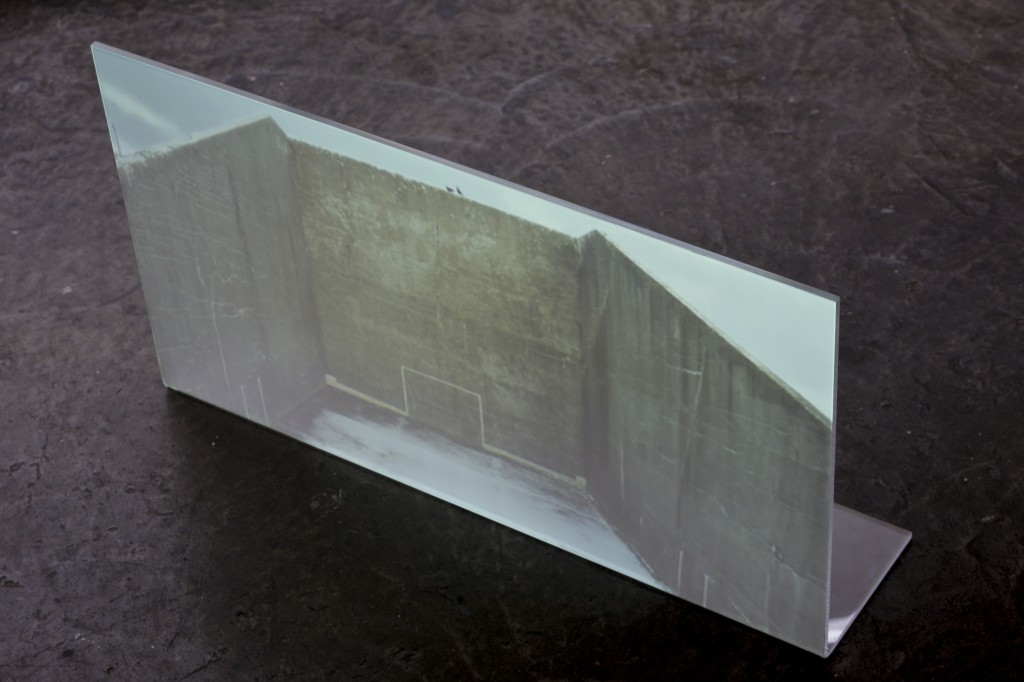

Seán O’Sullivan’s A large hole (Big enough to fit your couch through) is a large stack of A4 paper that stands slightly aloof in the right hand corner of the gallery space. The first sheet on the stack reveals instructions on how to cut the sheet of paper so that it expands in a sliver of sliced paper to create a large circle (big enough to fit your couch through). Reminiscent of Félix González-Torres’s stacks of paper and piles of candies, this work seems minimalist in form but in fact is one which multiplies and expands with audience participation. Seemingly inert, it has infinite potential for affect.

Seán O’Sullivan: A large hole (Big enough to fit your couch through)

A4 paper stacked

2011

Photo: Paul McCarthy.

There appears to be a warp and weft of illusion in David Lunney’s wall mounted Deduction. The work reflects a combination of sources and media. Using Googlemaps to specify a specific location, Lunney then recreates that place with a series of layered images. The end result sits somewhere between sculpture and representation. Deduction, hanging on the gallery wall, is a typically framed art work that plays on dimensionality, focusing on the core elements of making and replication. On the balcony of the gallery almost in a rebuff to the density of objects below, Alison Pilkington’s collage and paintings serve an off-centre moment rendered through colour and consideration. The works also have a sense of symmetry that plays with notions of reality, and the depth of the painted surface, the printed surface, and of pigment.

Broadstone Studios

Debra Ando’s Constellations (2011) is a projection of what seems like an agitated print plate or a collection of magnified dust particles that emulate the complexities of the night sky. The installation is simple: an overhead projector in a small darkened room. Anja Mahler’s looped video This earth might be uninhabited (2010) appears like a mirage as the distinct tonal horizon line and the spectrum of colours are reflected from an unknown source onto a wall. Flashes and subtle shifts in the content of what we see results as an illusion of something far away and unknown, but ultimately familiar. The rainbow of colours appears as a reflection on a white wall and changes and shifts with the light of a controlled interior.

This sense is continued in Lynda Devenney and Eleanor Duffin’s Spatial context (2011), a collaborative artwork with video and sculptural elements. The familiar modernist architecture of University College Dublin’s (UCD) Belfield campus are presented to us on CCTV monitors, accompanied by an interspersed voiceover which offers a texture of human habitation to the empty scenes of the water tower, the library, the admissions block. The shots of these buildings emphasise the structures as dense and heavy. Colour blocks are introduced to trace the role of symmetry and the uncompromising resonance of the lines and geometry of these buildings. The sculptural elements of the installation mimic the architecture of the campus and the monitors nestle amongst the arches of these structures. The CCTV monitors carry overtones of surveillance spy culture. Andrezj Wejchert’s winning design for the Arts Bloc was chosen in 1964 and building work continued through the late 1960s and early 70s. With minimal central gathering points for students, and escape tunnels for lecturers the campus design has been interpreted as specifically aiming to curtail riots and protest by student groups following the events of May 1968 student riots in Paris.

Fiona McDonald: Ferromagnetic lunarscape

electromagnets, ferromagnetic dust, power supply, arduino board, electronics, dimensions variable

2011

Photo: Paul McCarthy.

A magnetic dance takes place on a shelf perched on the side wall of the room in Fiona McDonald’s Ferromagnetic lunerscape (2011) where metallic dust, placed on graph paper, dances in reaction to electromagnetic pulses. The movement is beautiful, ‘orderly’ and uncanny. The soundtrack allows another understanding of the workings of the cyclical rhythm of the metal shards. The work allows for a deliberate chaos that regenerates and repeats itself.

This cyclical ordering occurs in Colin Martin’s The bridge (2011). Two HD video projections on screens are placed opposite to each other, and the viewer is left standing between two places that appear identical. Each screen documents a similar journey through an anonymous place. First we see a view of the land from the sea, then a closer view of the shore where there are some lights and a generator. From the shore we move across a wooden bridge and back where we started. The work highlights the conventions of the moving image and the narrative conventions of the technological frameworks, genre devices, and instinct of film making.

Colin Martin: The Bridge

HD video, dimensions variable

2011

Photo: Paul McCarthy.

Transference offers coherence despite the splitting of artists into two venues. I have a hankering to see the work under the same roof, but this is perhaps because there is a sense of mismatch between the venues. The clean lines of Monstertruck and the vaguely spooky space of the Broadstone Studios somehow seem worlds apart. However, this does not detract form the quality of the work and in some respects heightens it.

Kitty Rogers is an artist currently based in Dublin.