The latest show at the Green on Red Gallery, curated by Chris Fite-Wassilak, concerns itself most emphatically with memory and the failure of the present to come to terms with things lost. Sparsely installed in the space is the work of Simon and Tom Bloor, Ruth Ewan and Michelle Deignan. Outside, we hear the monotonous drone of a sound piece by Ragnar Kjartansson, accompanied by documentary photographs, and some small-scale watercolours.

Simon and Tom Bloor’s work is most synonymous with the kind of temporal preoccupation that pervaded the exhibition. Resistance Through Rituals (2010) takes the form of large-scale black-and-white photographs pasted abruptly onto a backdrop of streaky white emulsion. Billboards came to mind, specifically those as they fade away and denigrate pathetically over time. Depicted in these images are children playing, but caught in such a way as to render them static, immobile. A certain athleticism is connoted, a kind of youthful vigor which finds satisfaction by and for its own means. However, the utopian ideal of childhood is quite literally stopped in its tracks with these children appearing poignantly powerless and trapped. In most cases, the images appeal to us; the children seem to be playing ‘up’ for us, showing off or performing. This places us in a position of responsibility; the echo of propaganda in these images undermines the utopian ideal of childhood. Resistance Through Rituals becomes a hazy construct. The ritual-as-resistance, recalling Georges Bataille, becomes a growingly problematic domain.

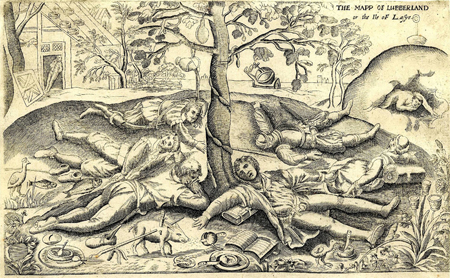

The failure of the present to deal with the conditions of the past is also a concern of the work of Ruth Ewan. Probably most well known for her 2007 work Did You Kiss the Foot that Kicked You? which involved commissioning one hundred buskers to perform a 1960s protest song on the streets of London, Ewan grapples with the recent past and the reliability of its manifestation in a startlingly amnesiac present. The Brank: The Damnation of Memory (2010) takes the form of a silently projected slide show and a glass table within which are presented postcards – to see the front of them we must peer awkwardly under the table. What we are presented with is places – the Netherlands, Houston, Salem and Finland – sometimes directly connected with witchcraft, often simply providing a temporary setting for the West End musical Wicked. The slide show continues in this vein, casually interspersing pop-culture depictions of witches alongside family snaps and medieval prints capturing scenes of abject torture. The personal and the objective historical cross paths and come to undermine one other. Thus, we recognize once again the sanitized myth that the witch has become, and the ramifications of this on the actual lived reality of history.

Michelle Deignan’s intriguing video piece, Journey to an Absolute Vantage Point (2009), takes the form of two channels projected on either side of a large screen, bisecting the gallery space. Both channels compete for our ears, the sound of a specifically commissioned tango piece threatening to overshadow our perception of a female monologue recounting a particularly dramatic encounter between her and a male companion. Footage of the idyllic grounds of a castle in Berlin echoes her monologue as she recounts their conversation which happened to take place there. As harmony breaks down, so too the reciprocal relation between sound and image. No longer referential, the image breaks down, moves away and grows more abstract. In doing so, reliability breaks down also. The conversation, resembling a kind of highbrow rambling Tarantino fare, becomes preposterous – “you haven’t revealed anything – nothing!” The hysteria of the conversation situates itself completely at odds with the pastoral setting of the video, and in doing so throws its naturalness into question. As the female protagonist states at one stage: “Focus can be so personal, so random.” The video of the tango musicians reiterates this also; personal history is depicted as interpretation, and history more generally is filtered through a process of de-naturalization.

The last component of the show was to be found outside of the main space in the Green on Red, in the hallway before entering. Ragnar Kjartansson’s work took the form of a sound piece, documentary colour photographs that referenced the sound work, and some watercolour drawings. Thus, two of these components referenced an earlier performance entitled The Great Unrest (2005), which consisted of Kjartansson dressing up as a Viking and playing endurance-blues for hours on end. What we are left with here is the residue of said performance; sound and photos that mythologize what is essentially an experiment in de-mythologization. Parody saturates the work, and yet it holds a poignancy that accompanies the death of myth in general. It seems that for some reason Kjartansson laments this loss of faith, and by such feats of endurance attempts to retain them. Asked at one stage as to why his work held such poignancy Kjartansson replied: “Because life is sad and beautiful, and my art is very much based on that view. I love life; I love the despair of it.” There is something both sad and beautiful about the work on show here, a kind of desperation witnessed both in the faltering intonations of his voice and in the small drawings depicting disembodied tongues resplendent with a childlike hint of stringy saliva. These hastily and sparsely drawn tongues are disconnected and impotent. They cannot make a sound, but exist only in a vacuum of history, and of myth. It is to this vacuum that Kjartansson speaks, a vacuum at once emancipatory and painful.

Oneiriography provides a welcome entrance onto a Dublin scene whereby the group exhibition exists as coded-manifestation of the ‘anything-goes’ logic of much contemporary art. Well-curated throughout, all five artists retain definite standpoints whilst holding much in common. All speak to a past that is yet to be deciphered, and probably never will be. How to reconfigure the present in terms of an ambiguous past seems top of the agenda, and this makes for exciting and perturbing art.

Rebecca O’Dwyer is a writer who lives and works in Dublin.