Neil Carroll: Working Backwards

installation shot

The Joinery

2011

Photo Miranda Driscoll.

Neil Carroll’s exhibition Working Backwards makes direct references to the world of building and architecture. Architecture is functional and tends to be planned and pre-designed. Carroll’s work experiments with traditional materials and uses them in a more organic way to explore creative expression and concerns. In his constructions, he reverts to the most basic and primitive of building materials using, for example, elements such as the grouped hexagonal tiles similar to foundation structures for bridges. His architectural organism develops and expands, moulding into the space and adapting.

It comes as a surprise to know that Carroll is a painting graduate. Inside, the visitor is immediately faced with what looks like the perimeter of a building site: floor to ceiling timber frames, a bare panel, clamps and cords firmly obstruct the path forward. Rather than serving as a deterrent, however, the objective becomes to step around. From the other side, the panel is painted and unfolds into a multi-layered construction that serves to draw us back further into the room. Bare fluorescent lights, placed at the foot of both constructions in the first room, project raw, unfiltered light. These light the pieces, but also give a sense of depth and weight, emphasising the physicality of the constructions and the tensions that hold them in place.

Neil Carroll: Working Backwards

Installation shot

The Joinery

2011

Photo Miranda Driscoll.

Carroll’s solid constructions are a meticulous work of labour and there is a fluidity in the progression of the show. Beginning with the cord that stretches between the door frame and the first construction, continuing on with the timber beam that leads us from the first construction to the second at the back of the main gallery, where two more panels are painted. One panel is painted in pinks, greys and blacks with geometric patterns, the other in a more muted palette with linear designs. The work resembles a network of suggested lines to follow, possible entries to breach, and objects to circumnavigate. Choosing to cut through the improvised tunnel is not for those wary of confined spaces and necessitates squeezing between timber frames and painted panels, being turned sharply to the right before popping out at the other end. Sitting on the ground to the left are some small, white hive-like huts made of plaster – a reference to primitive building and a return to basics. Rightly assimilated, however, to a ‘multi-directional map,’ there is no one, fixed path to follow; the visitor chooses how to traverse the terrain and whether, for example, to walk through or around.

Not content with the traditional method of displaying paintings, Carroll brings them into the viewer’s immediate floor space, thus collapsing the divide between viewer and artwork. Painting is no longer viewed on a wall, but something that can be circled as a three-dimensional object and viewed from an alternative perspective.

Progressing from the main gallery into the back room, this sense of compartmentalised space suddenly gives way to a higher ceiling. A large, painted canvas is stretched across the side wall depicting an industrial-style workhouse scene with figures hunched over mid-task. The open sides of the workhouse building and a gaping hole in the floor reinforce the illusion of spatial regression. A precisely engineered metal object sits on the floor. It is small and symmetrical.

Neil Carroll: Working Backwards

Installation shot

The Joinery

2011

Photo Miranda Driscoll.

At the back of the room, a human shaped object wrapped in black plastic and duct tape, stands upright within a timber frame. An opaque, plastic sheet is stretched across the back of the frame. An additional enigmatic feature of this intriguing piece – who or what lies beneath? Lit from behind with a construction light, the figure mirrors the anonymity of the workers in the canvas. Rather than functioning as independent objects, the large canvas and two sculptural pieces collaborate and speak to one another.

As a point of interest, the frame supporting the figure is constructed from the stretcher that previously supported the painting hung on the wall. Again, Carroll’s concern with disassembling and reassembling traditional architecture is reflected in this recycling of materials where the functional becomes part of the aesthetic and the decorative.

As a venue, the Joinery proves particularly fitting for the show; the asymmetrically divided space, with one room higher than the other, allows the work as a whole to become a form of site installation that would possibly not fit so neatly into another space.

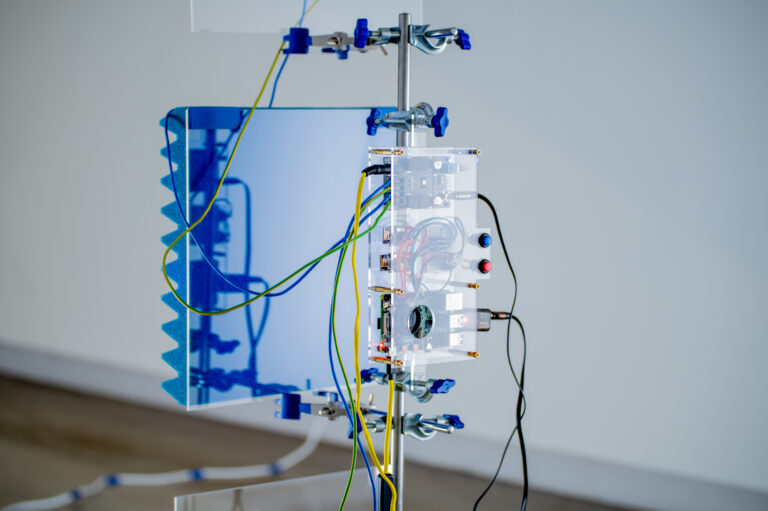

Sound performance by Guillaume Beauron at the Joinery

2011

Photo Miranda Driscoll.

During the course of this exhibition, sound artist and composer Guillaume Beauron was invited to compose a one-off sound piece in response to the work. Using a variety of devices and instruments, Beauron created a physical link between his composition and Carroll’s installation by hooking up the small welded object to his sound system and using it as an instrument. As the sound echoed around Carroll’s constructions and the gallery space, visitors were invited to move around, experiencing the work in a new light, and understanding the music as a direct response to the installation. A variety of sounds featured, including the murmur of voices, the sound of water and the drumming of and pinging of various objects to hand. This sound response filtered through and filled the space. This conversation between the artists seemed particularly pertinent to an installation where the manipulation and alteration of space is key.

Working backwards is an invitation to consider potential manipulation and containment of space, resulting in the ability to create a new spatial experience while adopting simple and unpolished materials.

Roisin Russell lives and works in Dublin.