After an hour on a bus crawling through the gridlocked traffic of a grey Thursday evening, the sight of Kilmainham gaol, the small glow of the lamp over its iron gates, comes as a strange kind of comfort to me. Across the flagstones and over the threshold, this is not my first visit. I was once brought to the museum as a child, so there’s a hazy sense of déjà vu about the entrance hall. All of the historical details, the facts and figures from audio-guides and wall-charts have long dulled out of my memory, but I can still picture the cells and corridors and dungeons.

Tonight I am here to attend an event organised by Performance Art Live, curated by Amanda Coogan, Dominic Thorpe and Niamh Murphy. Entitled Right Here, Right Now, the press release has told me to expect “twenty leading live artists performing simultaneously over a four-hour period throughout the cells and open areas of Kilmainham gaol’s East Wing.”

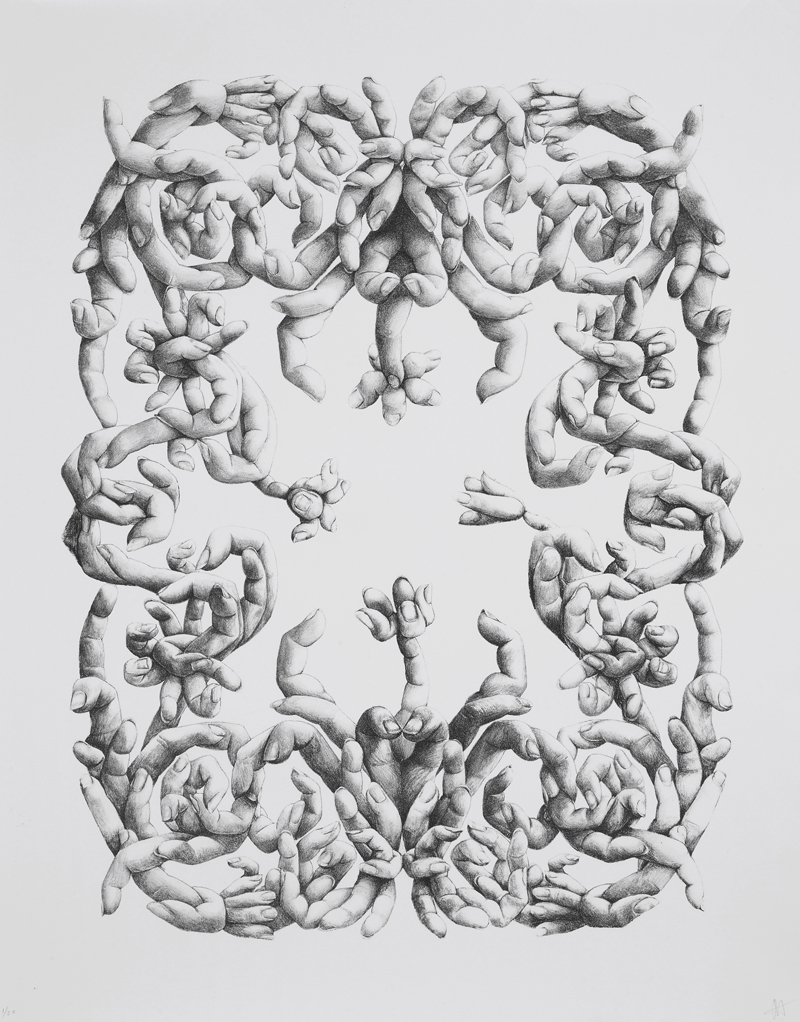

I am past the museum, across a prison yard, down a narrow corridor and through another door before being met by the East Wing’s commanding architecture: three stories of iron and concrete in an unfinished oval joined by a towering stairway, and capped by a cathedral-like glass roof. Yet it is not the building that strikes me, but the crowds. I am met by something I’d never imagined, by a wall of audience, and amongst them, a miscellany of props. Amputated branches, sheep’s fleeces, a trail of lemons, an arrangement of wooden crates, suspended steel buckets and salt blocks. There is the smell of boiled potatoes and damp brick. There is the sound of singing, sweeping, skipping, and more quietly, shuffling feet and whispers from the assembled throng.

Long lines have formed outside certain cells, and it feels odd to have to queue for things in the world of visual art. If it isn’t one of Carsten Höller’s slides or Tomas Saraceno’s inflatable domes, I just don’t expect to replicate a mundane post office type of experience in an extraordinary art space. What is interesting about the East Wing crowds is how they momentarily obscure the performers – not the isolated ones already obscured behind locked cell doors – but those that are skilfully floating about the floor. It takes me a few moments of watching before they become recognisable by their odd costumes, their eerie reveries and the way they blank all of the expression from their eyes, the way they glide like sleepwalkers across the cold stone.

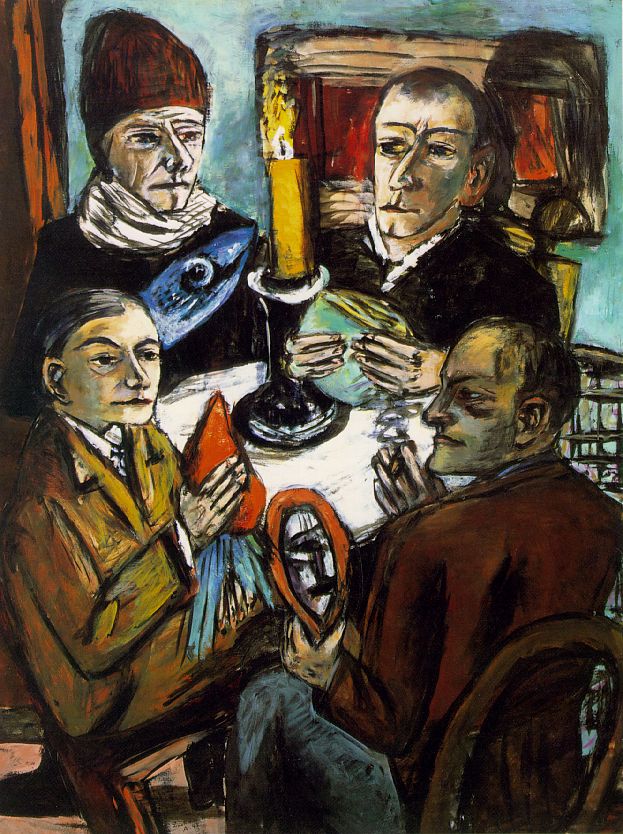

While I may have forgotten most of the gaol’s historical specifics, I am moved by the weighty atmosphere of the place; it is reverential, almost church-like. There is none of the protocol of your regular exhibition opening here tonight. There is no question that I might strut about wielding a wine glass or engage in voluble conversation with any and everyone I happen to know. Instead, there is an unspoken but common respect for the performing artists and their considered rituals, as there is for the history that hangs in the air around them – a history of the ordinary men, women and children who slept inside these walls as much as of the legendary leaders of the Easter Rising that were executed outside them.

I had been handed a sheet of paper on my way in, but I see now that it contains no information beyond each artist’s summarised bio and a map showing their designated spaces. Right Here Right Now is a difficult-to-ignore title – at the same time provocative and ambiguous. The Here of it makes me think of how apt the location, of how refreshing it is to feel that the art community has claimed back one of our national monuments from the Dublin tourist trail – if only for a night. The Now of it makes me consider a sentence from Amanda Coogan’s website which caught my eye. In an Irish context, the event “offers an articulation of the second wave of performance in the visual arts,” it says. A wave that, it suggests, is less reflective of its Northern Irish political legacies than it is of Kilmainham on a drizzly Thursday night, the Here and Now of the title. I am also reminded of Alastair MacLennan’s quote in the press release, on his admiration for artists “…who overcome the most, within and outwith themselves, ‘take on’ the human condition, and who (in effective art) comment on political and social corruption.” I suspect that most of tonight’s performances make some form of reference to contemporary society and politics, and manage to do so by simultaneously acknowledging the fractured past of their surroundings. No doubt I could spend a long time trawling the gaol’s archives for smartass connections, but I fear that this would somehow risk diminishing the raw energy of the event, the distinctive mood – the undercurrent of spookiness and the familiar shivers down my backbone.

I don’t know that I understand performance art exactly, but I have decided, in recent years that I like it. I like its abject weirdness. I like its immediacy, its intensity, its spontaneity, its lack of explanation, its lack of apology. And I have come to realise that performance, because it can be so intimidating and so changeable, demands a different kind of commitment from its viewers. More so than any other form of visual art, performance demands patience in order to sincerely react. And in light of this, I’m sure I will be sorry, afterwards, that I did not commit to undertake the full four-hour marathon with the artists themselves – to let the crowds wash over me and wait as spoken testimonies grow garbled and lipstick kisses spread across stone walls, as the performers tire of their respective trances, as they flag and falter in human error.

Instead, I drift back out into Kilmainham, into the cheerless murk of a Thursday evening, the thinning traffic and the falling leaves, the bar of the Hilton burning brightly across the street, but with hardly any revellers to prop it up. Most of the front-facing windows on Inchicore road are lighted now, and inside, I imagine, the ordinary men, women and children of contemporary Dublin are living out a strange kind of twenty-first century freedom in front of their LCD screens and with, unbeknownst to them, a whole fortress of ghosts and sleepwalkers right on their doorstep.

Sara Baume is a writer based in Dublin and Cork.