Artists often address political, social, historical or current issues in their work in order to respond to or influence our understanding of the world. Artists, like activists, may shape our own views in order to stimulate change.

During May 2010, two artists exemplified this approach in separate bodies of work. Both addressed the current issue of institutional abuse in Ireland. Dominic Thorpe’s show Redress State- Questions Imagined was shown in Galway’s 126 gallery, while Hardy Langer’s The Lost Boys was exhibited in Letterfrack, County Galway.

Thorpe’s live Redress State – Questions Imagined, was devised as a long-running durational performance. The artist spent days and weeks in the 126 gallery developing the installation which confronted the infamous Redress Board that promised to provide a safe and healing environment for victims of abuse. In his artist statement, Thorpe pointedly writes that “the artist will be present.”

Walking into the gallery, an assistant informs the viewer about the Redress Board. Victims are required to sign a ‘gagging clause’ whereby they may not speak publicly about their experiences. The viewer is also informed that the work may be disturbing due to explicit content, and that a torch is provided for the darkened space.

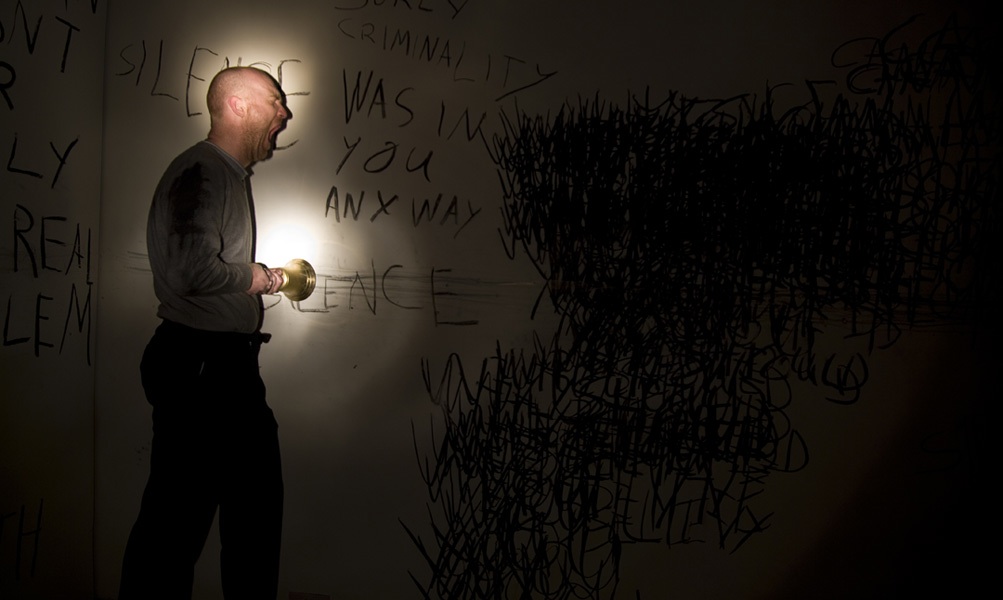

Upon entering, the pitch dark room is heavily scented with the oily lanolin of sheep’s fleeces piled up; it is a visceral smell. Torch beams highlight middens of creamy wool mottled with black stains. These smears also cover the floor as hundreds of thick charcoal sticks have been crushed underfoot by artist and audience. Thorpe picks up a piece of charcoal and resumes writing large scrawls on the white walls of the gallery covered in layers of text. He imagines discomforting and invasive questions asked by the Redress board to victims. He writes the word ‘silence’ over and over, mouths an inaudible cry and strikes an unsounding bell while covering his head and body with sheep wool. The entire experience is immersive and unsettling.

Thorpe’s performance is porous; we enter and absorb. Like victims, the viewer is kept in the dark, able to see only fragments of a whole. The smell, the crushing underfoot, the proximity of the artist, all combine to render us feeling complicit and enmeshed in the work.

The closing of the exhibition functioned as a public event. Under the glaring flicker of the strip-lighting, the dirty wool were like swirls of pollution in Galway’s canals, and the harsh statements on the walls were embarrassingly intimate. A series of talks took place which included speakers such as Margaretta D’Arcy, an artist and activist, who recently proposed a resolution to Aosdana on the procedures of the Redress Board, and Olive, a survivor of institutional abuse who has been campaigning for many years on behalf of survivor’s rights, spoke passionately. Thorpe enables the very form of communication, exchange and sharing of ideas, banned by the Redress Board itself.

German sculptor Langer engages with similar issues in his exhibition titled The Lost Boys that opened at Letterfrack the week following Thorpe’s exhibition. Langer, who learned of the notorious Industrial Boys School, began developing a beautiful installation that has taken sixteen years to be fully realised.

Hardy Langer: The Lost Boys

pillows, iron bed

Letterfrack, County Galway, 2010

Photograph: Jane Talbot

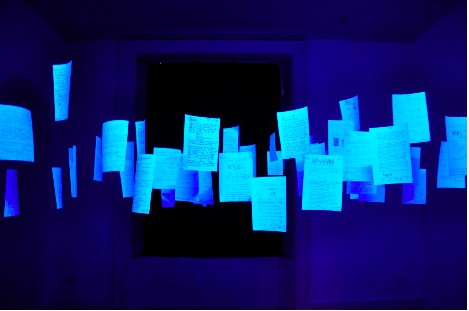

In a disused, empty concrete mechanical hall, a vast flock of pillows float ominously over iron bed structures. Like ghosts rising from the naked frames, they hang as though to suffocate, insulting their natural property of lightness and provision of comfort. Seventy-seven small portraits painted with turf dust and tea stains on biblical pages, line the walls for the boys buried in the Letterfrack Industrial School’s cemetary. A detailed text of the history of the school contains a disclaimer by the artist which states: “As an artist, I do not feel adequate in my ability to transform the pain of the boys of Letterfrack into an artistic work. My imagination is not big enough to fully comprehend the suffering and the terror of the boys.”

Both artists attempt to speak on behalf of those who are unable to; Langer on behalf of the boys at Letterfrack, and Thorpe for the gagged claimants of legitimate compensation. Thorpe describes one of the roles of the artist is to take responsibility for his or her language, and what it imparts.

Hardy Langer: The Lost Boys

pillows, iron bed

Letterfrack, County Galway, 2010

Photograph: Jane Talbot

They are using a form of media to journalistically address social inequalities. Many artists have done this. Millet’s The Gleaners, Picasso’s Guernica, Abramovic’s Balkan Baroque 1997 and Kathe Kollwitz’s entire body of work are some examples. Recently, Irish artist and politician Mannix Flynn performed the astonishing and powerful James X at the Abbey Theatre as part of Our Darkest Hour series dealing with the same content.

David Hare, the creator of Verbatim theatre [1] in the late 1990’s wrote: “We think we know, but we don’t. It’s one thing to know and another to experience.” Langer and Thorpe have both recreated realities into visual languages so that we may understand or feel, and hopefully in response, act for beneficial social change.

Áine Phillips is an artist and writer based in Galway.

[1] Verbatim theatre is a form of documentary theatre in which plays are constructed from the precise words spoken by people interviewed about a particular event or topic.