In his 2010 book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr describes cartography as one early example of an ‘intellectual’ technology.[1] With the map’s invention, he claims, a collective sense of the world was irrevocably changed;[2] but – and here’s the rub – it remains unclear whether its after-effects were ever fully mastered or anticipated by the human. This idea of technology is central to Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone, on view at Limerick’s Ormston House until the end of May.[3] The exhibition itself resembles a kind of system: originally curated by CCA’s Matt Packer and Alissa Kleist, this is its third configuration, having previously manifested at CCA Derry~Londonderry in 2016 and at Uillinn West Cork Arts Centre earlier in 2017. At Ormston House, Joey Holder has been sucked into its orbit; at Uillinn, Jennifer Mehigan. In this final iteration, we have works by Holder, John Russell, Alan Butler, Clawson and Ward, Pakui Hardware, Andrew Norman Wilson, and Eva Fàbregas, whose Self-organizing system (2014) seems an apt description of the exhibition more broadly. There is a real vitality to this exhibition: a distinct sense that, though carefully curated, the works might somehow misbehave.

At times, the possibility of object-led delinquency is quite direct – as with Fàbregas’s work, which takes the form of a small floor-based installation (Self-organizing system), comprised of small, motorised packaging materials that eke modestly around the gallery floor; alongside a snaking cushioned sculpture, the fairly self-explanatory, Object for sitting (2016); and lastly a digital animation, The role of unintended consequences (Sofa Compact, 2016), which presents us with the multifarious life of a commodity – in this case the first ever item of flat-pack furniture, Charles and Ray Eames’s Sofa Compact (1954). In each work, there is a preoccupation with animism, with the mischievous vitality of objects and, more precisely, with commodities. Because if, as Marx famously had it, the commodity serves only to obscure the human relations (labour) that precipitate it,[4] then in Fàbregas’s works that reification is upturned: these are overtly social commodities; from the anthropomorphic components of her Self-organizing system to the sofa-protagonist of the digital animation (‘there is no predicting what may happen in the life of a sofa’). As we move around the gallery, careful not to crush them underfoot, as we sit on them, watching an animation about something we sit on, we interact with these objects on quite a literal level. Fàbregas’s objects extend, perpetuate, and even seek out the disavowed sociality of their origin.

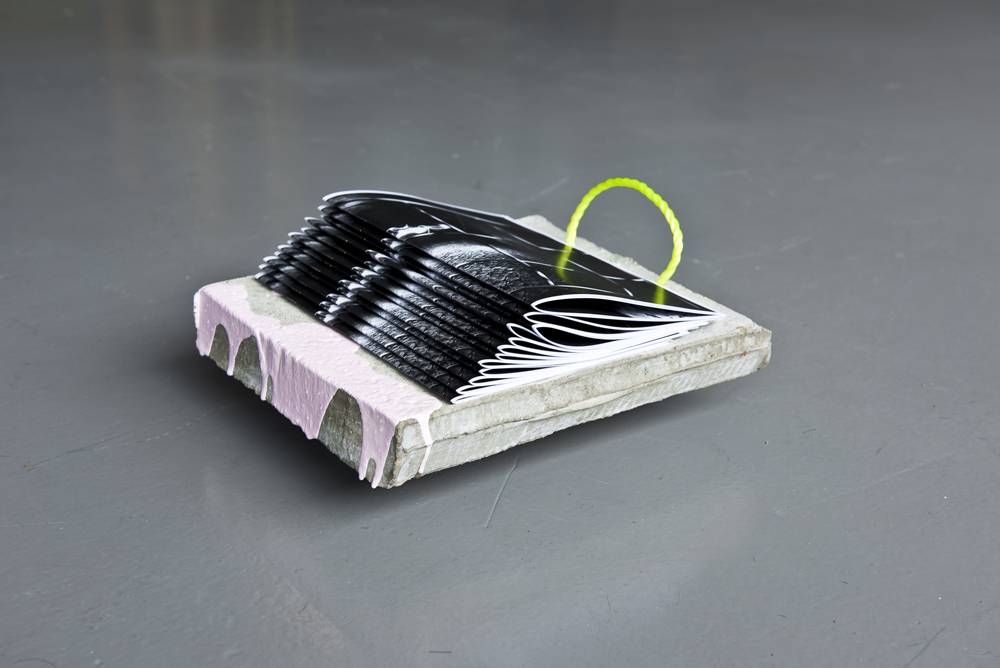

Installation view of Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone

Ormston House, 2017

Featuring works by Eva Fàbregas and Clawson & Ward

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

Courtesy of the artists and Ormston House, Limerick

John Russell’s work occupies the gallery’s two large walls: on the left, Parallel Domination Facility (2015), and to the right, Diagonal Slaughter Optimisation (2015). Judging from Russell’s previous output, there is at least some playful hyperbole to these titles, though possibly not very much: the two huge digital prints, backlit in a sordid red, fully dominate the gallery space. Their scale adds to a sense of twisted religiosity, frescos hewn towards some ill-defined purpose. With each there is a suggestion of narrative, but it’s unclear whether they are to be read from left or right, or whether it is their particular reversibility that is the point. The tableau of Parallel Domination Facility is occupied by an array of hybrid figures: a not-quite ostrich or emu; a figure that is part deer, part leopard, and part woman; while to the back, a naked man leans over, grasping at something in a gesture similar to that perplexing figure in the background of Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe.[5] On the right-hand wall, Diagonal Slaughter Optimisation depicts a similarly disjointed scene, but more muted tones, this time, showing a collection of figures, again resisting total classification, dancing around something that resembles a techno-futurist maypole. There is a debauched excess to both works: their relative flatness, being digital prints, compounding this impression, inasmuch as no figure appears to take prominence. Perhaps they are depictions of a techno-utopia to come, some primeval and orgiastic ground zero of cyborg-hybridity; but in his playing of a speculative gap – from now to a hypostasised ‘then’ – Russell seems to delight in ambiguity.

Playing, similarly, on this ambiguity is the short video Reality Models (2016), by Andrew Norman Wilson. Based on a memorable sketch from the 1980s children’s TV show Peppermint Park – extended here to nightmarish effect – the film opens with an explosion:[6] the smoke and racket clear, and a straw-man puppet appears, hunched forward in languid inaction, his strings visibly sagging. Music starts up and shortly thereafter he dances for what seems an uncomfortably long time – his limbs akimbo, his body parts diverging from each other in non-anatomical glee. At this point, and we’re told as much, the puppeteer rests; but the puppet, well he keeps moving, retreating alongside another puppet towards a somewhat purgatorial backstage area. Finding what looks like a fridge, which then explodes, we are led back without any pause to the beginning. Wilson’s works are typically preoccupied with language, and, in particular, with the languages – corporate, technological, etc. – that shape human behaviour. Reality Models, I think, could be seen as an extension of this, a playful and uncanny representation of systems of meaning – or cyclical perpetuations of reality – that are in fact meaningless.

Like the game of its title, the exhibition often seems to transmute human physicality into something other, but unlike the game the language that converts it is not strictly our own: it is technological. We can see this clearly in the indistinct reordering of the human by both Russell and Wilson. Placed to the front of Russell’s Diagonal Slaughter Optimisation, and just in from the gallery’s large window, there are two smallish sculptural works by the collaborative duo Pakui Hardware. By turns warm and regimented works, both titled Transactions (2016), we can sense something of the reordering particular to the exhibition’s title. These are simple, elegant structures, two floor-based columns of transparent PVC, granted casual solidity with red spring clamps; they appear almost stifled in a moment of unfurling. Printed on the PVC’s surfaces are images selected from the NASA digital archive: billowy clusterings of soft pinks and blues, their pockmarked surfaces lunar, almost. It is unclear what these images represent, exactly, their comprehension being further muddied in the images’ arrangement. What does remain, however, is a distinct material confusion, the fleshy, corporeal tones of the prints – themselves technological artefacts – becoming somehow seductive through their technological construction.

Installation view of Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone

Ormston House, 2017

Featuring works by John Russell, Eva Fàbregas, and Clawson & Ward

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

Courtesy of the artists and Ormston House, Limerick

There is a wide, nearly vertiginous range of ideas at play in this exhibition, and, at times, Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone appears more like a collection of moving parts, distinct but drawing energy from some common dynamism. They coexist and communicate with one another in ways that are fluid but often obtuse. On first glance, Anna Clawson and Nicole Ward’s works appear less reducible to this system. Killing time and everything else (or the passerby who stopped to watch) (2016), one of two floor-based sculptural works, is a self-standing construction comprising a used escalator handrail drawn in and upright, tight, like a concertina, encased in aluminium. Nearby is the floor-based steel branding iron, ROP (2016). These two sculptures repurpose industrial materials into new forms that belie their former use. ROP in particular seems an unlikely size for any practical act of branding. Less formalised, a large print-drawing hybrid, This ear says that the artist is not well schooled in anatomy … the ear screams and shouts against anatomy… (2016), hangs alongside, its title deriving from Stalin’s appraisal of a less-than sufficient portrait of his ear; it is a close-up of this feature, scrawled over in permanent marker, that is now magnified and reversed. In all three works, image and industrial form appear to hold a certain fetishistic charm, composites of subjective and objective – or ideological – import.

In both Pakui Hardware and Clawson and Ward’s works, then, we can observe the meeting of bodies, minor ones, with broader and seemingly more objective systems of knowledge. Elsewhere, the organic is made strange in technological translation. Joey Holder’s The Evolution of the Spermalege (2014–ongoing) is a wall-based installation, immediately phallic in appearance, and situated beside the gallery entrance. The spermalege is an evolutionary tool developed by female bean weevil insects, and also bed bugs, to offset the implications of traumatic insemination – which essentially means that the male impales and inseminates the female wherever he can. A technology of the body, the spermalege is a hack that allows the female to provide a localised target for this violence, and in so doing to stem the harm inflicted. At Ormston House, however, Holder represents it through its inverse, what it responds to: a series of 3-D-printed phallic forms jut out from two of the gallery’s walls, themselves covered in digital reproductions of weaponised penises. There is a terrifying masculinity to the work that slips variously into the realms of sci-fi and the “sexy” machismo of sports advertising (‘Just Do It’). Hence, whereas Holder’s work is entrenched and created by the technological, it appears the violence of the natural world is just as novel and horrific: up close, indeed, the distance between them appears negligible.

Installation view of Scissors Cut Paper Wrap Stone

Ormston House, 2017

Featuring works by Alan Butler and Joey Holder

Photo: Jed Niezgoda

Courtesy of the artists and Ormston House, Limerick

Alan Butler’s works hold an uncanniness I couldn’t immediately pin down; it is only in retrospect that I realise why his appropriations of Yosemite Valley seem so second hand. Preformatted as the standard desktop wallpapers of Apple computers, these are nothing images: staggeringly beautiful, sublime, even, but nearly always replaced by other, more personalised images, as soon as you begin to use your computer (Yosemite also lends its name to a previous Apple operating system – now of course outdated). Punctuated throughout the gallery space, three paintings of the valley by Albert Bierstadt, dating from the late nineteeth century, are engraved onto mirrored acrylic planes about the size of a painting that might happily sit above a grand fireplace. Now out of copyright, the images – their proximity to painting now only tangential – hang from lengths of chandelier chain, rotating and becoming permeable as they subsume their environment: me, other artworks; they lose solidity in the same way that the original images, cast free from authorial fixity, become refracted and indistinct. Like their high-definition, contemporary simulacra in the banal computer wallpaper, Butler’s ‘orphan transpositions’ are unstable,[7] capricious things: cast through technology, they become blank, ready only to be filled.

Rebecca O’Dwyer is a writer and PhD candidate at the National College of Art and Design. She is editor of Response to a Request.

Show runs: 24 March–27 May 2017

Notes:a

[1] Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2010), 116.

[2] Ibid

[3] The exhibition’s title comes from a 1994 science-fiction novel of the same name by Belfast-based writer Ian McDonald.

[4] Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1: A Critique of Political Economy (London: Penguin, 1990), 281.

[5] You can see the figure here.

[6] By memorable, I do mean terrifying; other once-children seemingly in agreement, it has been uploaded to YouTube for posterity. It can be viewed here, but I don’t necessarily recommend watching it.

[7] The titles of the three works are Orphan Transpositions (Albert Bierstadt, Merced River Yosemite Valley ii); Orphan Transpositions (Albert Bierstadt, Merced River Yosemite Valley iii); and Orphan Transpositions (Albert Bierstadt, Merced River Yosemite Valley iii) (all 2016).