Along a stretch of the Danube that spans the Romanian-Serbian border, lies a 143-kilometre gorge, known in English as the Iron Gates. Once considered to be the most treacherous point on the river, today the gorge is better known for being home to the Đerdap: a hydroelectric dam composed of two colossal gates built in the mid-1960s by the former-Yugoslavian and Romanian governments.

During the construction of the Đerdap – derived from the Persian word ‘girdap’, meaning ‘whirlpool’ – excavators unearthed a number of alien-looking sculptures. These objects were later attributed to the people of Lepenski Vir, a Mesolithic settlement once situated on the Serbian side of the river, and were declared to be among Europe’s oldest monumental sculptures. Little is known about the people of Lepenski Vir, but it is believed that they may have buried their dead in the river, facing upstream.

Barbara Knežević, Gvozdene Kapije (The Iron Gates), 2025. Film still. Courtesy the artist.

Both the gorge, Gvozdene Kapije, and the dam, the Đerdap, play a central role in Gvozdene Kapije (The Iron Gates), Barbara Knežević’s recent exhibition at Solstice Arts Centre. (A touring version of the show opens on 4 October in Sirius Arts Centre, after which it will travel to Wexford Arts Centre, before finishing its run at the Regional Cultural Centre in Letterkenny.) The exhibition tells the story of the Iron Gates through a singular filmic and material language, composed in part by a range of organic and industrial matter – jesmonite, driftwood, mild steel, clay, Serbian jezik (tongue) – and in part by a forty-six-minute film, also called The Iron Gates. The film opens in a large, windowless setting, where an archaeological survey of sorts appears to be underway. One by one, stones are laid out on top of a deep red tablecloth, over which the camera passes in a slow, left-to-right tracking shot. Cutting to a piece of archival footage from the dig, we watch as soil is brushed from the face of a rock, revealing a fishy mouth and wide, stunned, staring eyes. Then, the stone begins to speak.

Along with the Dunav (the Danube), a sheer rock cliff called Treskavac, the Đerdap, and the huge anadromous fish who once spawned there, the Moruna, this stone, named Water Fairy, is one of five phenomena or forces to be given voices in Knežević’s film. Together, the elements make up a kind of abstruse, polyphonic chorus, in which each element takes turns narrating its material makeup, its origins, its at once vengeful and sensual relationship with the other elements. Each voice lends its element an eternal, omniscient quality, as though it preceded its namesake not just in appearance but materiality. Each element is also danced by one of five dancers. It’s possible I have imagined this simple one-to-one casting, but the symmetry is there: five elements, five voices, five dancers. The film has a slow gaze, a deep red colour, and is full of the sound of rushing water.

Barbara Knežević, Gvozdene Kapije (The Iron Gates), 2025. Film still. Courtesy the artist.

It is also partly autobiographical. In the 1950s, Knežević’s grandparents migrated from Yugoslavia to Australia as refugees in the wake of the Second World War, and in The Iron Gates, we find the artist attending to her diasporic identity for the first time in her work since she was a student.[1] In one scene, Knežević appears in a richly decorated hotel room surrounded by a suite of deep red furnishings. Seated in front of a mirror, she slams a lump of clay on the desktop before her, quietening a rush of sonic turbulence, before addressing the viewer in voice-over. Speaking in Serbian – a language she has learned to speak in recent years – she questions her ontogeny, then her artistic drive, situating this impulse within the site’s history of industrial processes. Following this interior scene, the film cuts to a group of five cloaked figures standing by a body of water, stooped over a castle they are building from the earth. As they attempt to shape the mud together with their bare hands, a series of voice-overs provides a history of the dam, detailing its brutal design, its extractive processes, and its legacy of destruction.

In reality, the construction of the Đerdap redoubled the border, disrupting the natural flow of the river and causing numerous migrants fleeing Romania for Yugoslavia to be washed into the plant. The dam caused the waterline to rise so drastically that entire islands were submerged, displacing the populations of whole towns and villages. The moruna is now a critically endangered species, in a large part owing to dams like the Iron Gates, whose construction obstructed their ancient migration routes. In the first of Solstice’s three gallery spaces, hanging steel chains recall these industrial processes, referencing the experience of Knežević’s grandmother, Vukosava Grbić, who was sent to work as a forced labourer in a munitions factory in Nuremberg during the Second World War. In the film, Knežević reads aloud an English translation of a correspondence she discovered regarding her grandmother’s deportation. Knežević presents these facts as part of a teleological interpretation of the site, as well as a wider meditation on her practice: likening her process to the turbines of the dam (subsuming everything indiscriminately, conducting and transmitting energy), uncovering symbols in the earth like the Danube, and finding an affinity with the moruna’s instinct to return to their place of origin.

Barbara Knežević, Gvozdene Kapije (The Iron Gates), 2025, installation view, Solstice Arts Centre. Photo: Louis Haugh. Courtesy the artist and Solstice Arts Centre.

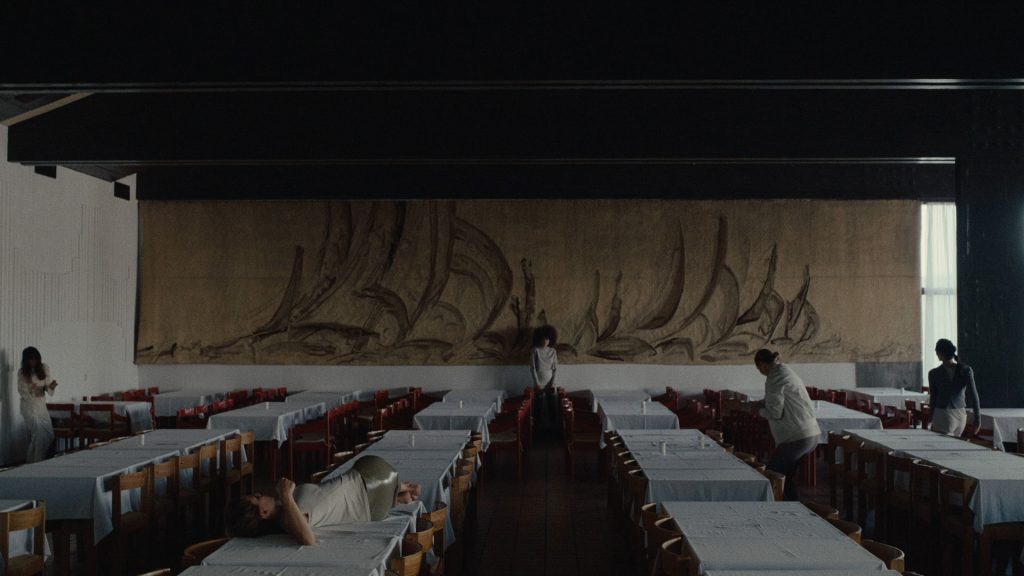

Throughout the film, Knežević and cinematographer Dušan Grubin make repeated use of slow, left-to-right tracking shots – along a welded chain tapestry, along the reconstructed bank of the Danube in the Museum of Lepenski Vir, along rows of steel blades lying idle in the grass in a remote storage facility – inviting the sense that a transcendent presence is presiding over the dialogues, as though the film (or the world) was in a process of witnessing itself. The film’s self-consciousness is most apparent at the outset, where in a conspicuously movie-magic moment the first line we hear is: ‘Sound?’ / ‘Rolling.’ / ‘Action’. This quality surfaces again in the final image, in which five actors – playing the Danube, Moruna, Treskavac, Water Fairy, and Đerdap – are shown recording voice-overs in a studio. These interpolating scenes perforate the container of the story, drawing attention to the vernacular form of its delivery, and highlighting the artist’s presence within the assemblage. In the film’s final moments, a group of figures dance in distinct solos in a dining hall. Some still, some frantic, they eventually converge into a cluster in the centre of the room: five forces, five actions, each one vying for space beside the others. As the scene builds, the sounds of steel clanging and rumbling machinery become the grinding of a cello that, together with a wordless vocal track performed by Serbian ethnomusicologist Tijana Stanković, accompanies the dancers in a final, climactic montage.

Barbara Knežević, Lancima, 2025, installation view, Solstice Arts Centre. Photo: Louis Haugh. Courtesy the artist and Solstice Arts Centre.

The film is shown alongside a number of new sculptural works: hanging shapes in welded chain, earthily pigmented steel tubes, strangely vital earthenware virgules in prokaryote or blood-cell forms, unevenly fired conch-like deckled stoneware, driftwood from the Danube. These objects are held in place by the structure of the gallery, embracing its limits, even seeming to disappear into it in places. This feeling of permeability extends into the second gallery space, where a soft, high-pile rug lies underfoot, its deep red colour forming a conjunction with the film playing above. Knežević is particular about the placement of colour in her work, having previously used chroma key greens/blues and rose quartz as motifs in other shows. Here, she employs a baroque Bergmanian red belonging to the Dulux ‘Red Stallion’ family (a cousin of which was used in her 2016 sculptural arrangement The Last Thing on Earth), eliciting a sense of interior turbulence and invoking the rich, subconscious, psychic activity we associate with the production of symbols.

The third gallery contains another arrangement of objects – animal hides figured in scaly clay, suspended steel curves that mimic the whirlpool’s arcing currents. In the centre of the space stands a grid-like formation called Strata (2025). Consisting of four overlapping mesh levels on which a handful of small fired objects has been arranged for display, it is an iteration of a form that appears throughout Knežević’s work: complex arrangements displaying difference and relation, in which the conspicuous properties of materials are played out against one another in contrived, dramatic scenes. Here in the dark, the objects are laid out as if for classification, but the attempt fails: driftwood explodes through the mesh, and instead of being categorised, the mute, primordial objects are left to languish in their own shadows.

Barbara Knežević, Strata (detail), 2025, installation view, Solstice Arts Centre. Photo: Louis Haugh. Courtesy the artist and Solstice Arts Centre.

Throughout the film, improvisations performed by Serbian accordionist Vladimir Blagojević accompany archival footage of the dam’s construction, his furtive accordion drones evoking the monumental creaking of the dam’s enormous turbines. Elsewhere, original compositions by the Irish artist and musician Karl Burke – written in an oddly televisual, Stockhausen style – are used to evoke the alien prehistory of the totems, which appear intermittently lying face-up in the landscape. White noise features throughout the film – part industrial, part weather, part water – whispering and groaning tectonically as it settles into the armature of our perception. It sounds like scrambled data, but peacefully so, like a busy brain about to dream. On the floor in the first gallery lies a collection of ceramics, Proto (2023), resembling a cluster of benthic invertebrates or diacritic marks. Suspended in the rumbling sediment of this sound, they look as though they might soon be swallowed up by some huge, unseen fish.

Aphra Hill is an art writer, researcher, and producer based between Donegal and Dublin. She is currently co-authoring a book on ritual art traditions and is a producer with the exhibition club Dirty Solutions.

Notes

[1] Barbara Knežević on The Mothership Podcast, 4 July 2024.