When I recently moved from the city to the countryside, my immediate impression was silence: a sudden absence of car alarms, blaring music, street noises, dogs barking, and people yelling for no reason. Instead, there was – initially, at least – nothing. Then, gradually, the ear began to adjust, attuning itself to distinct tones, subtle reverberations, pitches previously unrecognised by a typically overwhelmed or oblivious listener. A warbling trill of birdsong; a distant, muffled thrumming. The disconnected chatter of unidentifiable squeaks, croaks, and chirps. Rainfall. Insects. A relay of calls and responses. ‘A whole song of whistles and sighs.’ [1]

Between the Tremor and a Murmur Lies the Sunset, curated by Lorena Moreno Vera, draws on a personal history of such sonic encounters: from the 2017 Mexico City earthquake, with its convulsive shifting of tectonic plates and eerily unsettled aftermath, to a plangent score of squawking seagulls in Dublin. As the title indicates, these sounds resonate across multiple spheres, from the geological to the vegetal, the celestial to the tidal, and to humans themselves (although not necessarily as the end-product of all this activity; people are merely one aspect amongst many others here). The Martinican writer Édouard Glissant is a touchstone throughout, and, as per his notion of transversality, the exhibition exemplifies the non-linear, the rhizomatic, and the convergent: ‘Submarine roots: that is floating free, not fixed in one position in some primordial spot, but extending in all directions in our world through its network of branches.’ [2]

Between the Tremor and a Murmur Lies the Sunset, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, installation view, 2025. Photo: Markus Gradwohl. Image courtesy Kunstraum Niederösterreich.

One gets a sense of Glissant’s intent in the exhibition’s opening piece, i build my language with rocks: ash rain (2025), an intricate cat’s cradle of volcanic fragments suspended mid-air, held aloft by intertwined strings and the considered distribution of weight. These rocks have been temporarily borrowed from the Aeolian Islands by ~pes, the collaborative duo of Elizabeth Gallón Droste and Pablo Torres, who have arranged and amplified them via intermittent pulses of sound from subterranean field recordings. A causal reaction happens: trembling bass emanates from speakers perched overhead, cables quiver and vibrate, and a swaying chunk of solidified lava rotates in space. Seismic activity begets a faint, almost imperceptible, rumble, and ‘a continuously variable impulse or momentum that can cross from one qualitatively different medium into another’. [3]

Niamh O’Malley, Sun, 2023. Photo: Aisling McCoy. Courtesy Kunstraum Niederösterreich.

This effect can also imbue silence with trepidation, or clamour with disorientation, or any number of seemingly unconditioned responses. It filters into the atmosphere, seeps into water and soil, and is transduced into the observer. [4] In Niamh O’Malley’s Sun (2023), there is no evident heat or energy emitting from the screen, yet the titular orb glows with a searing, pixelated intensity that makes it difficult to look at for too long. Its edges blur and fray, blending into the video’s scorched, saturated resolution, while rays of light seem to beam out from the squat, squarish screen. It is dizzying, disorienting, evocative of parched thirst and prickly skin. (Almost) like the sun itself. In Edgar Calel’s Ru K’oxk’ ob’ el nu k’ux / The Echo of My Spirit (2025), an embroidered landscape reflects the spectrum of sounds in the Guatemalan highlands; lyrics to a song used by the artist’s late grandmother to call birds, alongside repeated staves and signs denoting an idiosyncratic ‘score’, and the outline of an active volcano, with a spurt of bright-red stitching to mark the moment of eruption. The tapestry is hung loosely, framed by a cloth window, and layered by colour and density: the mountain vista is spacious, airy, while the undergrowth is crammed with sharp lines and sideways letters. In Calel’s work, sound coincides along multiple registers, handed down over generations and across species, occasionally incomprehensible but always ever-present.

Between the Tremor and a Murmur Lies the Sunset, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, installation view, 2025. Photo: Markus Gradwohl. Image courtesy Kunstraum Niederösterreich.

The attempt to articulate the incommunicable, even while acknowledging its inevitable omissions and distortions, rings throughout the exhibition. ‘I have heard pieces of the aural fabric in such gloriously clear detail, a way to decipher the language of the wild, important secrets left unspoken or unheard, a path of discovery, a divine revelation.’ This is how the narrator in Tania Candiani’s For the Animals (2020) describes their pursuit of the natural and artificial noises that comprise an acoustic ecology. The work unfolds as a three-screen collage of kaleidoscopic patterns, schematic diagrams, night-vision footage of foxes and coyotes in the Arizona desert, and sound waves ascending into inaudibility: ‘20 Hz at the low-end, to 20,000 Hz at the high-end.’ While the promised ‘divine revelation’ proves elusive (perhaps I was tuned into a different frequency), there are distinct moments of connection between subject and spectator, as the voice-over’s staccato delivery keeps pace with the film’s rapid-fire, spliced, and sped-up torrent of imagery. Orla Barry’s Milk the Ewe (2016) offers a similarly equivocal encounter. A wall-sized triangle of letters, reminiscent of an eye chart, collapses into repetitive, nonsensical chants: ‘THEETH THEE HEHEHEHEHEHEHE WEMILKEUUUUTHEE EUH? EUH? EUH? EU! EU! EU! EUW! EU! EU!’ The font gets larger as it descends and, as such, becomes increasingly frenzied, louder, and more shrill. Except, of course, that it’s just writing. The artist has a sheep farm in Wexford and, given this information, one can variously ‘hear’ the script as a plaintive call, an invocation, as glossolalia, mimicry, or bleating (or perhaps even as a deranged diatribe on the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy and its subsidies for sheep farming: ‘Milk the EU’ indeed). Traversing this large-scale text, from top to bottom and across the breadth of the body, the reader becomes a conduit for Barry’s words, as they enact an internal, soundless, and spellbound recitation.

Between the Tremor and a Murmur Lies the Sunset, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, installation view, 2025. Photo: Markus Gradwohl. Image courtesy Kunstraum Niederösterreich.

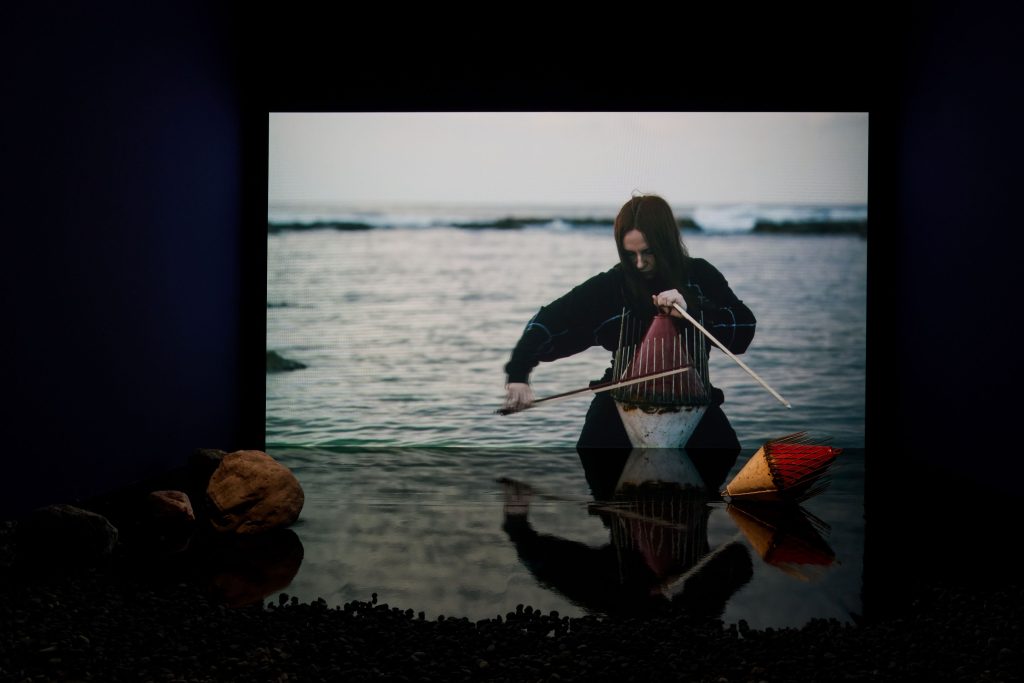

Glissant writes: ‘Along their trail, all the way to the rocky mound marking the distant Morne Larcher, one can sense the power of a hurricane one knows will come. Just as one knows that in carême, the dry season, this chaotic grandeur will be carried off, made evanescent by the return of white sand and slack seas. The edge of the sea thus represents the alternation (but one that is illegible) between order and chaos.’ [5] Despite this illegibility, the impulse to seize the ineffable (and to understand it, to command and translate it into our own words) persists. In Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán’s installation How to Mend a Broken Sea? (2024), pebbles and stones have been scattered across the gallery floor, while the film portrays the musician Diana Miron as she interprets the waves of the Black Sea, percussively beating the tines of a reconfigured buoy. The sea itself, a basin for multiple confluent rivers, contains layers of separated water – an upper, oxygenated level and an unfathomable, anoxic abyss (which accounts for its perfectly preserved shipwrecks) – and this unstable, ecologically delicate tension is sustained in Miron’s performance. She squats in shallow water, wailing, singing, and coaxing discordant notes from her impromptu instrument, in a valiant attempt to impose some semblance of compositional structure on the tempestuous, intractable, and otherwise uncontainable movements of the sea. It is an impossible effort, yet utterly engrossing to hear.

Chris Clarke is a curator and critic based in Vienna.

Notes

[1] Tania Candiani, For the Animals (2020), three-screen video, narrator’s voice-over.

[2] Édouard Glissant, ‘The Quarrel with History’, in Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays, trans. J. M. Dash (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 67.

[3] Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 135.

[4] ‘Like electricity into sound waves. Or heat into pain. Or light waves into vision. Or vision into imagination. Or noise in the ear into music in the heart. Or outside coming in. Variable continuity across the qualitatively different: continuity of transformation. The analog impulse from one medium to another is […] a transduction. In sensation the thinking-feeling body is operating as a transducer. If sensation is the analog processing by body-matter of ongoing transformative forces, then foremost among them are forces of appearing as such: of coming into being, registering as becoming. The body, sensor of change, is a transducer of the virtual.’ Ibid.

[5] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 121–22.