On a visit to their home in October last year, artist Michele Horrigan and her family took me on an eclectic trip around rural Limerick. We visited a pier on the Shannon Estuary that was once a centre for seaweed harvesting; stone circles; a tree stump on the image of the Virgin Mary; and the archaeological centre at Lough Gur. As we drove to the Aughinish Alumina plant, however, the trip took on a starkly different mood. My first view of the enormous facility was from an earthen bank several miles away, from where there is a clear view of an orange line on the horizon. This orange line is just the visible sliver of the piles of toxic waste the alumina plant has amassed over the last four decades. Horrigan warned me that the wind could pick up the dust. If it travelled in our direction, the smell would burn my nose. Primed for this sting, the other-worldly sight took on a disorienting sense of horror. It was so at odds with its environs. The horror only thickened as I realised my own ignorance of this toxic dump up until that point, even though I lived most of my life less than seventy kilometres north.

Michele Horrigan, Stigma Damages, The Model, Sligo, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

The Aughinish Alumina plant opened in 1983. It is Ireland’s largest industrial site and Europe’s biggest bauxite refinery. Originally operated by the Canadian company Alcan, the plant today is run by the Russian aluminium group Rusal, which has connections to the Russian military. The plant processes the mineral ore bauxite imported from Guinea, which is chemically converted into alumina to be exported and smelted into aluminium elsewhere. The toxic waste that is produced as a result of this process is dumped on an adjoining site twenty metres high. This waste cannot be treated, has no known uses, and is still growing, covering a 550-acre site in perpetuity. The site has a sprinkler system to prevent it from becoming drying and airborne, but it has long been suspected to be leaking into groundwater.

Horrigan grew up in the shadow of the plant, in the village of Askeaton, and her practice is dedicated to uncovering the legacy of the plant and its waste in the region. Stigma Damages, at the Model, Sligo, is the culmination of years of rigorous research into the heavy metal industry and its environmental impacts in Ireland and internationally, generating a dense archive of fieldwork in the process. This is the most comprehensive exhibition of this material to date and includes recent video work, archival material, and a new digital resources website. The title comes from the legal term for suspected environmental pollution, aptly capturing the impact of this metastasising environmental, political, and social contamination.

Michele Horrigan, Stigma Damages, The Model, Sligo, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

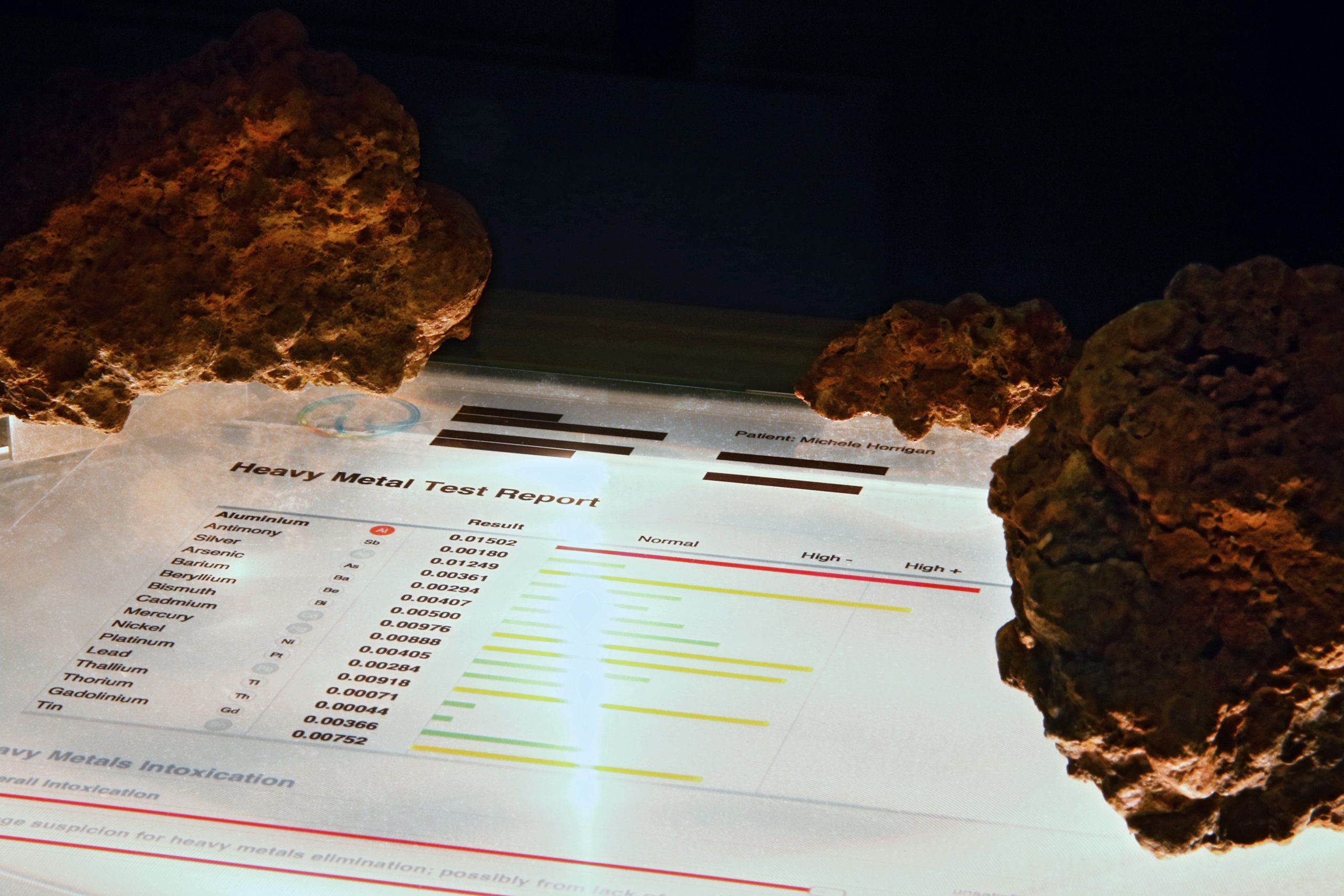

The first work on show is a two-minute video displayed on a suspended flat screen monitor mounted on metal supports in an otherwise austere room. The handheld camera documents a heavy metal test Horrigan and her daughter undertake that detects extremely elevated levels of aluminium in their blood. In the adjoining room, Horrigan has projected the test results using an overhead projector, framed by red bauxite rocks. As an introduction to the exhibition, Horrigan has quite literally exposed her own body to public view, exposing the metals within to daylight like an open cast mine, a painfully potent method of depicting the terrifying depths of this waste.

In the next room, another video work on a suspended flat screen monitor shows a short film by Horrigan on the history of the Aughinish plant and the pollution it has produced. Once the film ends, the screen cuts to footage of a local community meeting where the film has just been screened, the camera panning towards a man sitting at the back of the room who immediately begins to verbally attack Horrigan. He calls her a liar and seeks to remind those attending of the positive role of the plant. The meeting soon descends into chaos, as the man proceeds to defend his position against an increasingly agitated crowd, who explain how the plant has had detrimental impacts on their lives and voice their fears for the future. In editing the original film and the documentation of the community meeting together, Horrigan immerses the viewer in this fraught process and sheds light on the operation of mobilised vested interests.

Michele Horrigan, Stigma Damages, The Model, Sligo, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

Through press clippings, PR material, and found objects, minimally hung on large MDF room dividers, Horrigan illuminates how the owners of the Aughinish plant have twisted the truth to create misinformation. A tall poster features a heavily photoshopped image of birds, butterflies, and foxes against the backdrop of a bucolic wetland scene with a winding path leading up a grassy hill that half disguises the chimney of the plant. The poster is accompanied by a text reading ‘Nature Trails of RUSAL Aughinish’ and the Rusal logo. This fantasy scene signifies the plant’s investment in constructing a false environmentally friendly image. Elsewhere in the display of archival material, there’s a clipping from a December 1990 copy of the Limerick Leader with the headline ‘Aughinish hits back at critics’. The piece recounts three cases made against the plant by locals including a gardener whose plants failed to flourish, which Alcan attributed to a cold winter, verified by a UCD Professor of Plant Pathology hired ‘at a high bloody cost’.

In the final projected video work, Horrigan documents a trip to Western Australia where she evidences the horrendous health and environmental impacts of mining bauxite there as well as the tactics employed by the mining companies to win over the public and those in power. She attends a public sculpture festival sponsored by the local mine owner Alcoa, which has a specific Aluminium Sculpture Award. She also attends the Resource Technology Showcase in Perth sponsored by the mining giant Rio Tinto, featuring Australian PM Anthony Albanese in the driving seat of a CAT earthmover. The video ends with Horrigan interviewing a former worker at the Alcoa bauxite mine, Greg Subholz, in what appears to be a prefab office. Through a heavy cough, Subholz describes the conditions of ‘ring barky’ (peeling skin), which he developed as a result of working at mine. This international focus compellingly highlights how the industry operates across geographies. It strikes me it would also be useful to hear the voices of those working in the Guinea mines – the source of the ore for the Aughinish plant – considering the role of environmental racism within large-scale industrial pollution in the Global South.

Michele Horrigan, Stigma Damages, The Model, Sligo, 2024. Installation view. Photo: Cían Flynn

Through interviews, fieldwork, and her own direct experience, Horrigan sensitively pinpoints the human suffering that follows on from living in proximity to these plants, unapologetically calling into account the forces of capital underpinning this sickness and disease as well as the industry’s catastrophic environmental damage. At the same time, she undertakes the tireless work of gathering archival material that documents the strategies deployed by the industry to manipulate their public image so they can continue polluting with impunity. In addition to acting as a chronicler of the ills of Aughinish, Horrigan has also staked out the role of artistic research in resisting industrial injustices, providing a method for evidence-gathering as well as a tool for organising. This includes a call to action to join the campaign against Aughinish expansion led by activist group Futureproof Clare. At a time when Rusal is applying to dump its poisonous waste in the Shannon, this is vital work.

Iarlaith Ní Fheorais is a curator and writer.