Chris Hayes: I was interested in speaking with you about the references to early Christianity in your recent body of work shown as part of flotsam, jetsam, lagan and derelict at Void, Derry. I’m thinking of this in a broader context: how Irish artists approach older forms of storytelling, whether that’s early mythology or the legacy of Christianity, playing with shifting histories of belief on the island.

Isabel Nolan: My interest in Christianity is ongoing, particularly its tacit influence on the way ‘we’ think in Ireland or in the West. The early church is particularly interesting because it’s a complete admixture of history and legend and it incorporated so much pagan tradition. This is a heady combination, and the contingency of its evolution is so apparent. In relation to this show, I learned about St. Columba’s connection to Derry and that reignited my curiosity about him.

But perhaps more important to the way the show turned out is the impulse I had to display a lot of drawings alongside the new paintings I was working on. This felt like a change in approach for me, and made me kind of nervous. I mean, I don’t even know if a lot of the things being exhibited could be described as drawings – they’re sketches, or preparatory material. I haven’t considered, or felt comfortable, showing them in the past.

Installation view of Isabel Nolan, flotsam, jetsam, lagan and derelict, VOID Gallery, 2023

Courtesy of the artist and VOID, Derry

Photo: Simon Mills

CH: Drawing is often thought about having a relationship with thinking, right?

IN: Yes, I suppose. I keep a sheet of paper beside me when I’m reading a book or listening to a podcast. A lot of the works on paper included in the show began as scattered notes. It made sense to me to try to include this background material. I’ve always worked with source material in a quite intuitive way, so I’m reluctant to use the word ‘research’ in relation to the reading and material gathering that I do. This exhibition is a collection of paintings and other things, things culminating. I have a certain amount of control, however it was not planned months or years ahead and then executed. It rarely is. But for previous exhibitions, I have gone back, at a certain point, to one of my sources, or gone back to some moment of inspiration and looked to that source for a particular prompt, which becomes a good way to give a coherence to the show. It can end up dominating the way I talk about it thereafter.

In many respects, this is simply a way of organising an exhibition mentally. And it is also useful to open up the work to people, to have something to say about a particular body of work. For this show, I wanted to step away from that, to have a slightly different relationship to the work. Worrying a bit less about what the work was doing. And just sort of putting it out there. Seeing what would happen.

CH: I like the attention you’re bringing to that moment of sifting through and assembling material.

IN: Most of the drawing from the last two or three years is fairly recent. Mary Cremin and I went through it, spent some time, sorted through stuff, dozens and dozens of things on the floor, and then culled it to the selection that we brought up to the gallery. Connections emerge between things. It’s a kind of a document of all the stuff I’m interested in – and that I can’t let go of.

CH: I want to return to what you just said about reluctance with the word ‘research’. I was curious to hear a bit more about this changing relationship?

IN: Can I come back to that in a roundabout way? Because there’s one book that was very influential on the way I was thinking about the exhibition: Some Answers without Questions, a book by the British poet and writer Lavinia Greenlaw. Each time I come back to it, I find other things. I think it’s largely about voice.

She writes really well about tension, and I think this is very pertinent. The tension between inwardness and expansiveness, the tension between wanting to do stuff in the public realm, wanting to put your work out there, but also not wanting to be present, not really wanting to draw attention to yourself in particular ways.

And in some respects, I think I’m more present in these assembled drawings, in a way that I am not used to being within my own exhibitions. Greenlaw talks about this idea of risking presence. You’re retreating and coming forward, and retreating and coming out again. She talks about this in terms of brimming and shrinking.

I think the word research was used about me before I ever used it for myself. And the reason I don’t really want to use it anymore is because I’m not scholarly and I’m not academic. I am not creating ‘new’ knowledge in a defined field, not uncovering things. I’m synthesising material in a way that’s completely irresponsible.

If you were in my studio now, you would see shelves full of books. I am sort of addicted to acquiring books, reading unsystematically, and looking at lots of images – it takes me somewhere else. I think about it in terms of theft and tribute. I get interested in certain stories, people, histories, or objects. That interest turns into a desire to take something from that material. So whether it’s stealing, and maybe a formal prompt, or whether it’s using the story as a way to talk about the world that gives me a way to make something and present something in the world.

Isabel Nolan, The world is dusty, 2020, coloured pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Photo: Lee Welch

CH: I’ve heard a few other artists over the last few years increasingly frustrated or uneasy with this term, while still being totally immersed in books and collecting material. Part of the frustration, perhaps, is this pressure to rationalise or justify activities for funding bodies. The competitive justification …

IN: And producing new knowledge! You’re absolutely right. And I think there’s also a much more practical and kind of human dimension to it. You need to write a press release. You need to describe yourself, your interests and your work in – you know, a tiny bio, a few lines. There’s so much pressure on every single word, and there’s, I guess, a lot of fashionable terms and references that pop up; they can become hard to avoid.

CH: ‘Irresponsible’ is an important word you’ve used. It always seemed important to me that artists could experiment with ideas, put things out there, and do all this without permission. I think that relates to what I think people are doing when they’re returning to earlier stories, pre-Christian mythology as well as this early formative period, forgotten traditions, alternative forms of knowledge. The irresponsibility makes it generative.

IN: There’s a limited amount of information about these periods, which means there’s an awful lot of room for projection and peculiar forms of identification or empathy. St. Jerome, for instance, is an interesting and uninteresting figure. He had such a powerful effect on the history of Christianity, with his translation of the Bible into the Vulgate, and there are thousands of paintings of him. All the figures in the exhibition are people who had very extreme experiences – and lived very strange lives because of their worldview.

What I wanted to do with the painting is just to pay attention. To pay attention to the bonkers-ness of these stories and these quite beautiful moments. A few years ago, I went to Iona, the island off the coast of Scotland where St. Columba’s monastery was. There’s a little mound there: you couldn’t even call it a hill really. This is seemingly where he would go up high in order to have a good think about things, or to pray I suppose. That’s why I put him on a hill in the painting. Someone instantly acquires a kind of gravitas by literally elevating and isolating themselves. Maybe he thought it was taking him physically closer to God, but I suspect people have always known how to make themselves seem more important and unavailable. I think he was destined for sainthood from birth.

Isabel Nolan, ‘He could see behind himself’ (St Columba), 2022, water-based oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Photo: Lee Welch

You know, there’s this great story that I think appears in some of the hagiographical material. It turns out that St. Patrick hadn’t quite banished the snakes, but stuck them behind a river in Donegal in Glencolumbkille. It was Columba, aka Columcille, who completely banished them into the sea, turning them into these red, demonic fish. That’s quite magic. I’m sorry that those bits of the story of Columba don’t get told. It’s referred to in the painting, but not explicitly.

There are all kinds of odd portraits of people in the show, and one of the things that I think is interesting about these people is that they aren’t action heroes or historical figures who are changing the world in a straightforward way. They have that inwardness and expansiveness, which I think has to do with a form of creative thinking. There’s so much beautiful invention attached to the stories from the past, you don’t literally believe, or at least I don’t literally believe, that they’re true. But you believe that this person must have been singular and really special. Or equally that a story, an event, needed a person to hang upon, as a way to be told. Like poor Eurydice whose death is so tragic that she is destined to die twice.

CH: Many of the references seem intentionally quite opaque or indirect.

IN: Yes, absolutely, they’re almost invisible. There’s one little shadowy figure with tiny, malevolent red eyes looking out of a cave – it’s St. Jerome – but he’s hidden away. I don’t think I did it consciously initially, but none of the standard signifiers of a St. Jerome painting are included. Though the cave he is in is bright red, like one of the cardinal’s hats that always feature in paintings of him. And I deliberately took his lion away from him. I resent the fact that he gets to become this superhero. You know, through the story about how he pulls a thorn from a lion’s paw and then immediately it becomes devoted to him. It makes any possibly dull, unsympathetic man who doesn’t have a particularly interesting biography into someone special.

But you’re right this stuff is not explained, maybe they are just a reason to paint. Although I might know that I want to paint a certain person, the paintings take their own course. Sometimes the subject appears quite late in the development of the work. I used a lot of motifs from other places – from neolithic art, microscopic images of dust and diatoms to begin these paintings. And suns, of course. I’ve always painted suns.

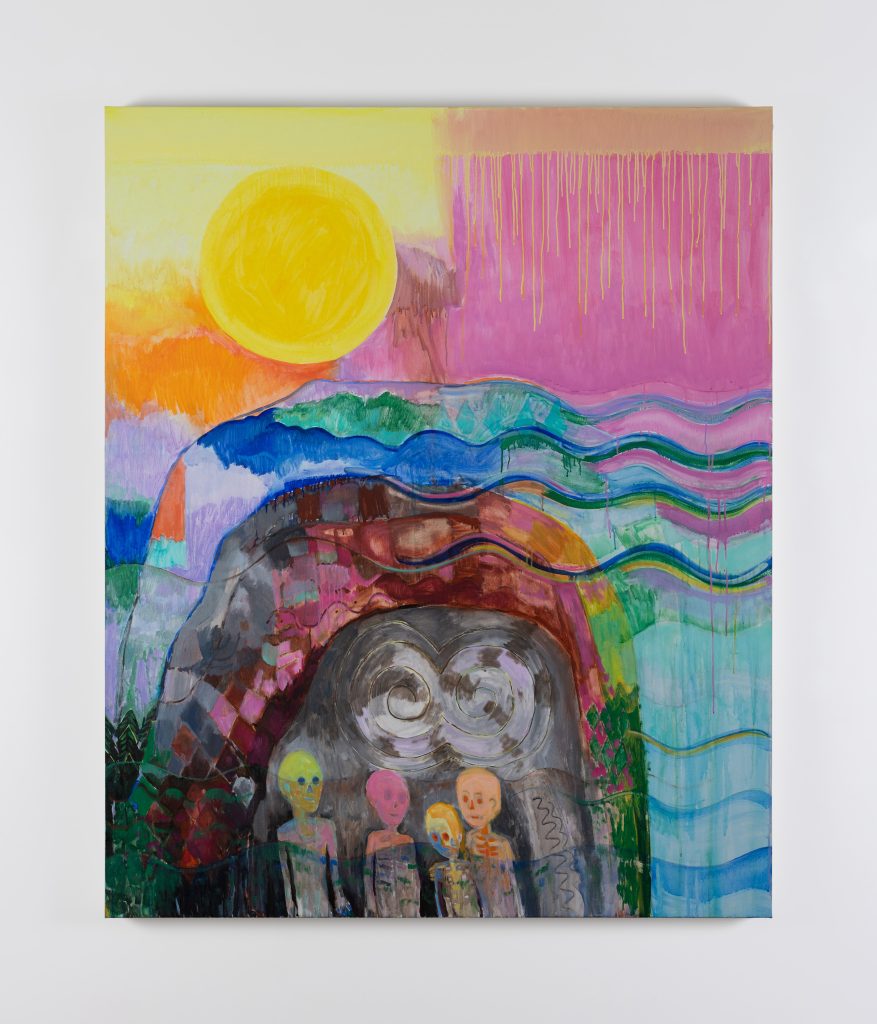

Isabel Nolan, Desert Mother (Saint Paula) and Lion, 2022, water-based oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Photo: Lee Welch

The reason that I painted St. Paula was simple. She’s an early Christian figure who gets completely forgotten about – yet she funded everything that Jerome did. She was a Roman woman who had five children, but her husband died before she was thirty. She inherited his wealth and devoted herself to Christianity. She built a monastery for Jerome to live in, and also looked after all of the pilgrims coming through. And apparently she also did an awful lot of editing and translating, building up a library for Jerome. She did all this heavy lifting without credit. So I thought Paula should feature and I gave the lion to her for a change.

CH: Yeah, absolutely. This is quite a purposeful return to a particular mythology.

IN: It’s something that Lavinia Greenlaw writes about as well. A great deal of what I grew up with was a white, male culture. That was what I learned to love – and then you consider the kinds of strategies, attributes, and impulses behind works, behind figures and people. You have to question them from another perspective.

I was kind of quietly schooled in feminism by my mam, which wasn’t something to take for granted in 1980s Dublin. There was also a reverence for culture, for literature, and for the arts in our house. And I still feed off the culture of dead white men, and I’m fascinated by it. Part of the fascination is finding the culture you grew up in alienating in ways that were very hard to fathom at the time. And now I have to do something with that love and alienation, and to work through it, to recognise the problems, the exclusions. I’m obsessed with the history of Christianity. It’s a good story, and an extraordinary engine of change in Europe and beyond.

CH: One that still has significant implications today.

IN: I think that’s one of the things about revisiting this material. It’s all still here. It’s bred into the culture of Ireland, it’s in our institutions. It’s in the way we’re taught, it’s in the way that our consciousness has been shaped whether we like it or not.

CH: That segues nicely into my next question. You took a number of site visits to Derry: did you encounter a lot of this material there? I was interested to hear a bit more about your relationship with the city and the context for the show.

IN: My first visit coincided with Aleana Egan’s exhibition at Void. The morning after the opening, I went to the Saint Columba Heritage Centre. The Columba exhibition is almost the first thing you encounter within the space. That sowed a seed. I’m interested in the extreme personalities and extreme commitments that people make to something that seems very esoteric and strange. So it was just visiting the city and knowing he was the patron saint of Derry.

Also, there’s another beautiful book, Angels and Saints (2020), by the American essayist Eliot Weinberger. There’s a very odd essay about angels and also brief biographies of various saints. He has taken great poetic licence with all kinds of hagiographical material. Some of his biographies are just two lines long. Columba gets a page and a half, and that’s where the title of the painting comes from.

Isabel Nolan, ‘Dead talk (archaeologists), 2022, water-based oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Photo: Lee Welch

CH: And when you say future events …

For me, there’s a sense in the exhibition that it spans time as some of the paintings allude to future events. And some of the works clearly relate to mythology, religion, archaeology. It’s as if the dead archaeologists I painted are close to the present moment – they’re an organising principle.

IN: The gallery was painted blue to a depth of 3.8 metres. All the tables are covered in glass, which is reflective, and likewise the vitrines with the small sculptures. I wanted it to feel like a swimming pool or a drowned world. And in the works, there’s a lot of imagery of waves, of things being submerged. It’s in anticipation of this material getting lost under water eventually. It’s not the most hopeful vision of the future. Some of the more abstract paintings depict future events, conflagrations, drowned material – one is titled System 3597CE, there’s nothing human in it. It’s why I used the title of the show that I used, because I want to allude to all of this human material, these cultural artefacts and natural phenomenon, all getting jumbled together.

Isabel Nolan, System 3597CE, 2022, water-based oil on canvas.

Courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

Photo: Lee Welch

CH: I had a question about the exhibition title as well because I liked that it seemed to embody something about the approach, right? A multitude of references and sources, bringing the different elements of your practice together.

IN: I think it’s important for me that I’m not pretending to be in control of this material. That was the point of putting all these drawings out there. Though of course, they’re quite carefully arranged…

CH: I was interested to ask about the connection with your upcoming public commission?

IN: Yeah, the public commission in Temple Bar in Dublin is really nice. It’s a modest project with quite specific parameters to do something within the surface of the pavement. There’s quite a lot you couldn’t do – like having any kind of raised surface on the ground, which would be a trip hazard. I’m working with stone for the first time. I made quite a straightforward proposal, but I am really happy with it. It’s a simple design of a sleeping dog, curled up on a rug.

CH: Is there a particular reference you’re making with the dog?

IN: I’ve drawn dogs previously. It’s based on a drawing of my dog. It’s simple: I love dogs, and I love seeing dogs in the corners of paintings, incidental dogs.

I was also thinking of it being in Temple Bar. Initially it seemed like it should be very eye-catching but I realised I wanted to do something quiet instead. When I leave my studio, the area is sometimes like a Bruegel painting. From around eight o’clock on a Friday night, the place is heaving, everyone’s having a good time. The drinking, people pissing, flirting, and the noise, and so on; it’s almost carnivalesque. And if you think of a Bruegel painting, there’s always a sighthound in the corner of that world.

There’s a connection of sorts, interior and exterior, between the drawings and this public artwork. This idea of something that’s more interior, this kind of thinking, making that public. And this public installation, again, a return to exterior, intervention, public space.

I found it very hard to think sculptural thoughts during Covid. And that’s where a lot of the drawings came from. It was very much an inward turn. And also there is a kind of work that I do when I think no one is looking, and don’t expect them to be looking. And this goes back to the exhibition, goes back to a way of working that I did when I was much younger. Back then, I didn’t know there were other ways to work, if you know what I mean. I would just make things and make things, and if I had a chance to show stuff, I would select things.

I’ve been more interested in painting the last few years. I haven’t made very large paintings since I was in college. There’s nowhere to hide in paintings. I think the way that I draw is a little bit similar. I mean, there are ways to hide if you’re a certain type of painter, but not the way that I work. And this is how it comes out, as I say when it feels like no one’s looking. That was the way I was working and I wasn’t thinking about the external world.

But, going back to the dog, it was pointed out to me a few years ago. There are always animals in my work. For me, they’re a kind of shorthand for the weirdness of the world.

CH: There’s something quite evocative about using stone. It’s full of different metaphorical resonances.

IN: When we were allowed to travel again, one of the first trips I took was to Rome. I hadn’t been there since I was about twenty or so. I’ve always loved mosaic floors, in museums, cathedrals, and places like that. I often take photographs of those floors. I love stone, I love terrazzo. I’m also interested in looking at the ground. It’s something I’ve written a lot about, feet and the ground. The quiet, dirty world down there. Where things get a bit overlooked.

Isabel Nolan is an Irish artist who works in sculpture, painting, textiles and text and explores notions of reality and identity, and the human compulsion to understand and define our situations and relationships with others.

Chris Hayes is a writer based between Ireland and the UK. His writing on contemporary art and politics has been published in Tribune, Frieze, and Art Monthly.