The first time I encountered the work of the American choreographer, dancer, and artist Trisha Brown (1936–2017) was in, or rather just outside, a museum. We were on a family outing to Tate Modern in 2006 – I was a preteen whose cultural experiences were still very much orchestrated by my parents. I am not sure whether I knew what we were watching, but I remember being surprised and pleased by the spectacle that unfolded. We stood outside the building, on the north side facing the Thames, and craned our necks to watch a man strapped in a harness slowly descend the brick wall. I took photos on my pocket camera: grainy close-ups in which you can see the strain of exertion in the man’s red cheeks as he ‘walks’, his body at a ninety-degree angle to the vertical surface, his posture the same as if he were strolling down a regular street. He is wearing a T-shirt and jeans with grey Converse high-tops.

This performance of Man Walking Down the Side of a Building was the first time the piece had been staged since its initial iteration in 1970, when Brown’s then-husband Joseph Schlichter traversed all seven storeys of the building where the couple lived on 80 Wooster Street in New York. But the decision to stage the choreographer’s work at a museum was nothing new. Right from the start, Brown and her peers in the postmodern dance movement – figures such as Merce Cunningham, Yvonne Rainer, and Simone Forti, who held that anybody could be a dancer and that any physical movement could constitute a dance – found a home in the art world. When they weren’t performing in forests or a church basement, they took their dances to venues like the Whitney and MoMA. This was partly out of necessity: as Brown once put it, in 1960s and early ’70s New York, ‘no one under forty was invited into theaters’. [1] But what emerged as a result was a close-knit artistic community with little regard for the distinctions between different kinds of creative experimentation. Choreographers and composers and painters came together, not only sharing audiences but also collaborating and exchanging ideas and forms. (Brown herself had a deep interest in drawing, producing a significant body of graphic works.)

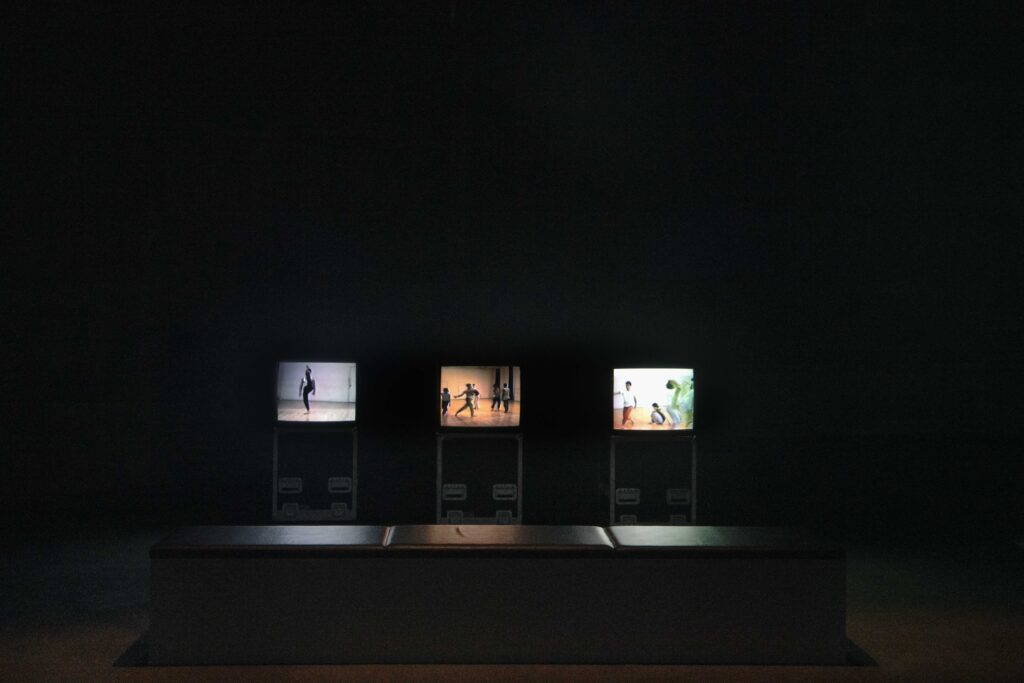

Trisha Brown, Set and Reset

South Tanks, Tate Modern, 2022

Installation view

Photo: Oli Cowling

Tate Modern is currently revisiting Brown’s choreographic work with a programme devoted to one of her most ambitious collaborations, Set and Reset, which premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1983. It was only a few years earlier that Brown had begun to produce dances for the traditional performance setting of the proscenium stage. With a score composed by Laurie Anderson, this was her first piece set to music. The stage set and costumes were designed by Robert Rauschenberg, who was a close friend and chairman of the Trisha Brown Dance Company. (Apparently, Brown invited him to participate on a whim during a board meeting in which she was presenting plans for the production. He asked who was doing the set and she responded: ‘Well, you are!’) The choreography was based on a technique that Brown called ‘memorised improvisation’, in which she and her fellow dancers devised the movements according to a series of basic principles. In comparison to her earlier projects – particularly the ‘equipment pieces’ using ropes and harnesses, such as Man Walking Down the Side of a Building – Set and Reset looked and sounded much more like a customary dance performance.

Trisha Brown, Set and Reset

South Tanks, Tate Modern, 2022

Installation view

Photo: Oli Cowling

Located in the Tanks, the museum’s dedicated space for performance and moving image, the Tate programme has taken a few different approaches to presenting the work. From January to September, you can visit a free display that draws heavily on archival material. On one wall, a text lays out the five principles according to which the dancers improvised their movements – ‘keep it simple’, ‘act on instinct’, ‘stay on the edge’, ‘work with visibility and invisibility’, and ‘line up’. On a trio of box monitors, videos show the rehearsals in which these movements were worked out. Brown liked to record ‘building tapes’ as a tool to assess and memorise the improvisations. On a large suspended screen, footage from the premiere of Set and Reset – the only time Anderson performed the score live – is projected. The picture quality is poor, so it is difficult to make out what’s going on, but it is nice to see the improvised solo performance Brown gave after the dance, draped in a piece of pink chiffon given to her by Rauschenberg. Another projection shows Babette Mangolte’s beautiful black-and-white film of Brown performing a different solo, Trisha Brown WATER MOTOR (1978). The film shows the dance once at regular speed and then again in slow motion – unlike the other recordings, this is not just a means of furnishing documentation but an original artwork in its own right.

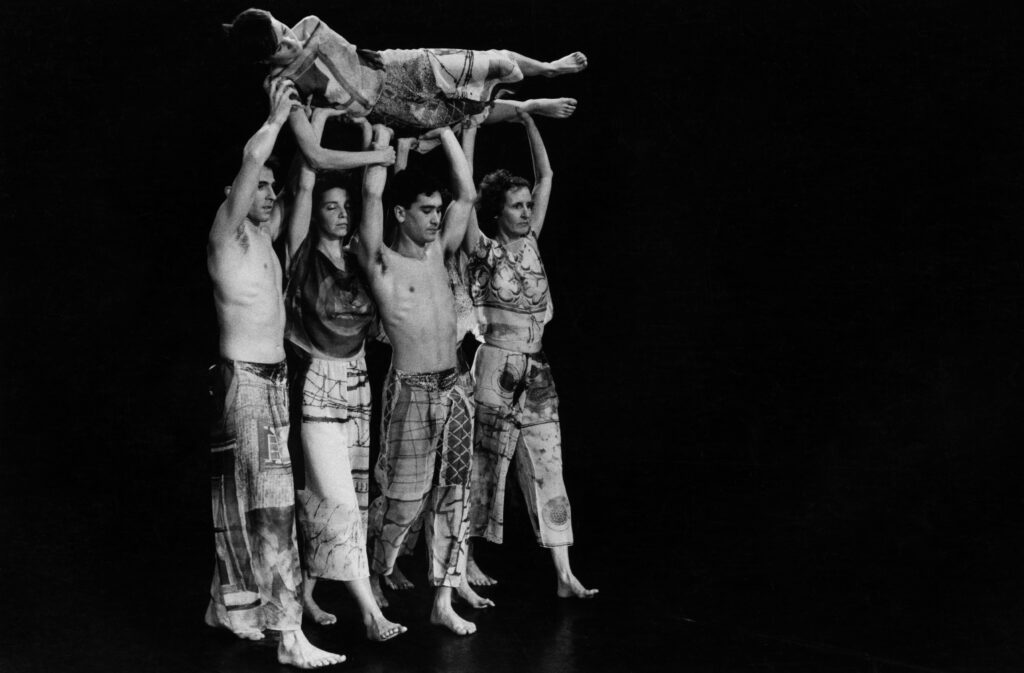

Trish Oesterling, Carolyn Lucas, David Thomson, and Gregory Lara in Trisha Brown, Set and Reset, 1983

Photo: Mark Hanauer

Courtesy of Trisha Brown Dance Company

At the centre of the display, however, is the stage for Set and Reset: the monumental sculpture that Rauschenberg produced for the performance. Hanging from the ceiling in a cordoned-off area with a slightly raised stage floor, a large cuboid structure made from stretched scrim is flanked by two pyramid shapes in the same material. Black-and-white film clips showing a random assortment of newsreel footage are projected onto the flat surfaces. Anderson’s energetic score, which layers words (the repeated phrase ‘long time no see’) with a cacophony of musical and electronic sounds, is blasted from speakers. On the premiere of the production, reception was mixed: some argued that these audio-visual accompaniments distracted from the dance itself. Artforum contributing editor Thomas McEvilley wrote that Rauschenberg’s contribution ‘drew the viewers’ eyes up and away from the dance’ – that ‘it was, in fact, in direct competition with the dance’.2 In the installation in the Tanks, the reverse is true: there are no dancers for the set to compete with. The space beneath the hanging shapes is too big. It is as if we are watching and waiting for a performance to begin.

For those fortunate enough to have scored tickets – me included – that is indeed what happened. During the three-week Van Cleef & Arpels Dance Reflections festival, held across multiple venues from 9 to 23 March, two different London-based dance companies took to the stage at Tate Modern. In front of an audience, sitting on scattered cushions plus a few rows of chairs, the Rambert Dance Company gave us the first authorised performance of the original choreography outside of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, complete with Rauschenberg’s gauzy screen-printed costumes.

Adél Bálint, Seren Williams, Comfort Kondehson, Conor Kerrigan, and Archie White from Rambert performing Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset

Tate Modern, 2022

Presented by Tate in collaboration with Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels

Photo: Hugo Glendinning

Courtesy of Candoco Dance Company

Next up, Candoco Dance Company staged their own version, Set and Reset/Reset, which was created following the process of principle-led memorised improvisation that Brown devised. The costumes had the same silhouettes as Rauschenberg’s, but the colours and patterns were tweaked. This was the third time that Candoco dancers, overseen by a former member of Trisha Brown’s company, Abigail Yager, had reconstructed the original choreography in this way (the previous iterations were in 2011 and 2016). The cast included disabled and non-disabled dancers, who made use of additional elements – a wheelchair, a crutch – to riff on the movement phrases in the original dance. Both the Rambert and Candoco performances came in at just under thirty minutes, but they seemed even shorter – exhilarating bursts of unpredictable energy. The dancers couldn’t keep the smiles off their faces.

This presentation of the original and reconstructed versions of Set and Reset in succession was a clever way of illustrating Brown’s rather abstract-sounding principles and process. The same basic themes and motifs emerged across the performances: the interplay, for instance, between geometric and organic forms, expressed in rigid angles formed by limbs or mobility aids versus the sway of hips and the curve of a spine. Brown’s sense of humour carried over, too: in the moments when dancers sprinted and crawled or collided with unexpected force.

Candoco Dance Company, Set and Reset/Reset

Tate Modern, 2022

Presented by Tate in collaboration with Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels

Photo: Camilla Greenwell

Courtesy of Candoco Dance Company

The choreographer was equally witty, it turns out, in conversation. Aside from the ticketed performances, the Tate programme also features a series of free events titled Set and Reset/Unset, running until late August in the Tanks, which take inspiration from Brown’s ‘informances’ – the term she used to describe her lecture-cum-performances in which she discussed her creative process alongside snippets of dance. On the day I attended, two Candoco dancers performed short sections of the piece – both with and without music – while video footage of the company rehearsing and Brown speaking during infomances played on a nearby projector. In one clip, Brown responds to the criticism of Set and Reset that there is simply too much happening onstage, what with Rauschenberg’s set, to take it all in. ‘If you’re split about what to look at, look at the dance,’ she suggests. ‘But don’t tell Bob I said that.’

Notes

1 Cited in Philip Bither, ‘Trisha Brown: From Falling and Its Opposite, and All the In-Betweens’, Walker Reader, 20 March 2013, https://walkerart.org/magazine/philip-bither-trisha-brown.

2 Thomas McEvilley, ‘Freeing Dance from the Web: On Collaboration, Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset and Lucinda Childs’ Available Light’, Artforum, January 1984, https://www.artforum.com/print/198401/freeing-dance-from-the-web-on-collaboration-trisha-brown-s-set-and-reset-and-lucinda-childs-available-light-35422.

Gabrielle Schwarz is an independent writer and editor living in London.