In his article ‘Remote Viewing’, for the June 2020 issue of Art Monthly, Morgan Quaintance argued that the rush to produce online content during lockdown has resulted in thoughtless overproduction from institutions that rely on standardised web platforms and models of reception not fit for purpose. Faced with the closure of physical gallery spaces, curators have taken a ‘knee jerk’ response, establishing an atomised relationship between the audience, interface, and institution. Without the ‘communal experience in spaces populated by other visitors, lurking staff or the incorporeal presence of behavioural expectations by disciplinary architectures’, curators are creating flat experiences. In quarantine people are isolated, alone, and lonely – sending links simply adds to the ennui and exhaustion that we’ve become so accustomed to. [1]

Alan Butler

TULIP_YELLOW

2019

Cyanotype

Courtesy of the artist and Green on Red Gallery, Dublin

Many Irish museums and galleries have, out of necessity, found digital means of presenting art and connecting with audiences during lockdown: Kerlin Gallery continued with a solo exhibition of new work by Samuel Laurence Cunnane in an online viewing room, and IMMA launched an archival film programme of six works by Irish artists over six months. Remote Joy is the first online exhibition by Green on Red gallery (partially supplemented by a private presentation in the gallery of a selection of work). I don’t imagine an exhibition like this would have been planned without such challenges, and as restrictions begin to be lifted, opportunities to view artworks in this way will likely once again be, aside from alternative projects such as Berlin Opticians and others, few and far between. Considering digital natives like Alan Butler alongside Irish painters deeply connected to the physicality of their practice such as Fergus Martin, Remote Joy offers a unique context to view Irish art practices. The artwork varies, ranging from high-res scans of paintings to GIFs and microsite projects. The concerns of the works stretch across direct references to Covid-19 to broader considerations of looking itself.

Alan Butler is an artist sensitive to the digital as a medium in and of itself. His high-profile Instagram project Down and Out in Los Santos (2015–present) mimicked the style of a photo documentary through the in-game lens of Grand Theft Auto V. On show as part of Remote Joy, his Virtual Botany Cyanotypes series translates imagined simulations of fictitious plants from video games and other such environments into physical prints – now presented again as JPEGs. Cyanotype photography brings its own associations of scientific enquiry, typically used as a process of cataloguing specimens for study. Applying serious scientific inquiry to video games and their imagined digital simulacra conjures the classic concerns of art criticism about what’s serious and what’s not; what’s art, science, or entertainment. Now, the work becomes a digital simulation again, having started as an intentionally anachronistic depiction of an imagined simulacra made of binary code – whoa. The National Gallery of Ireland bought a print in May 2020. Who’s brave enough to buy the JPEG?

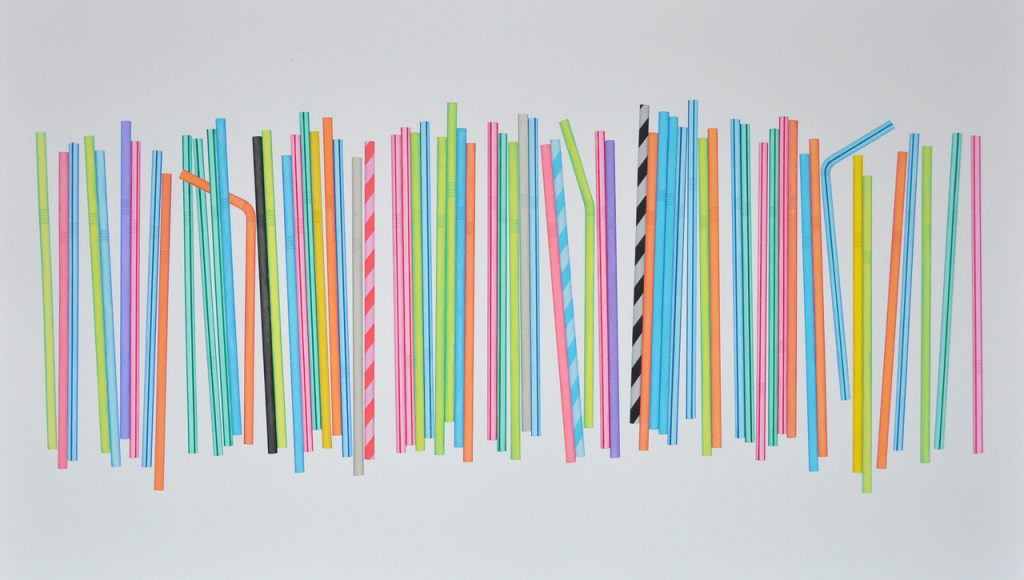

It may be over-reading things, to view JPEGs on a website as a profound new way of looking at, or understanding, physical paintings rather than simply a response to the situation at hand, a makeshift solution. However, I often find myself interested in what happens accidentally whether that’s an unintentional context or an inadvertent outcome of design. Behind such provisional gestures, there can be a generous, well-intentioned naivete, a certain kind of open attitude. The theme of the exhibition makes this explicit. The accompanying text from Jerome O’Drisceoil admits to the stopgap nature of the effort, ‘to show that art continues to be created, even in these trying and frightening times’. The aim of the show, he says, is to ‘bring some joy and art right into your homes’. Caroline McCarthy’s work embraces this fully. Made during lockdown in a newly adapted studio, her series of ink and gouache drawings, Together Forever (2020), each depicts the same set of colourful plastic straws. Offering a sly critique of plastic’s disposability, this ‘celebration drunk on colour and excess’, as the artist describes it, offers a visual stand-in for the kinds of social gathering that are no longer possible.

Caroline McCarthy

Together Forever #20

2020

Gouache and acrylic ink on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Green on Red Gallery, Dublin

That being said, the website is admittedly not good. It’s not terrible either, just noticeably OK. The architecture of the website itself structures and frames the works through the relationship with image and text in the browser. The act of viewing is a process of scrolling downwards: each section begins with the artist’s name, a blurb about the work, and a handful of JPEGS, GIFs, and links. The content conforms to what is presumably the limitations of the website builder – a little mid-noughties WordPress or a basic Wix template. The exhibition link is https://www.greenonredgallery.com/new-page, which to be clear is Green on Red dot com forward slash new-page.

Fergus Martin makes no sense here and it’s kind of thrilling. Two recent works are included: spray painted pipes hung vertically on a wall acting as glossy geometric sculptures. Online, the installation images are flat and don’t work. It’s almost like he’s resisting being included – crying out that you haven’t seen the art, only it’s documentation. In the accompanying text, Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith describes the works’ ‘contained density and stored energy’. He writes about unusual sculptural material, the passage of time and concentration. Nodding to modernist formalism, they couldn’t be anything but art; becoming charged by their presence in the gallery. On the other hand, Damien Flood, Mark Joyce, Kirstin Arndt, and others make physical paintings and drawings that sit well on the website. A zoomed-in shot or high-res scan of the physical piece communicates sufficiently, offering an odd no-go zone grasp of the object. One could argue that you haven’t really seen it. Not truly, not in real life, not in the flesh.

Ronan McCrea

Study for Projection (Sylvania DFF) Landscape

2020

Chromogenic colour print (Fuji Crystal Archive) mounted on diabond, edition of 5 + 1 AP

Courtesy of the artist and Green on Red Gallery, Dublin

What if the opposite is true? That with a good lens and modest Photoshop the work is tweaked to truly pop. In ‘The Perils of Post-internet Art’ for Art In America, Brian Droitcour wrote about a generation of artists who were making physical works specifically for their digital circulation. Despite a strong affinity for much of this work, he is strongly critical of its worst excesses; it ‘looks good in a browser just as laundry detergent looks good in a commercial’. Beyond a critique of tricks, Droitcour has a larger thesis here. It’s not that any approach is right or wrong but that the viewer and experience the artist imagines while making the work fundamentally shapes how the art is made and what it means. [2] Many of the artists in Remote Joy don’t typically – if at all – work with digital presentations in mind. The final point of interaction between object and audience is a physical space: to be mediated between the gallery, the labour of the staff, and the event of the exhibition. Every artist featured holds his or her own position in relation to the premise of the show. Sometimes this is outright resistance. Others can be read in new ways, intentionally and unintentionally. It is in this relationship that things become clearer about the artists, their work and our relationship to visual culture more broadly. There is something valuable about this provisionality, an improvisational meeting of expedience and emergency. It is a quality that could easily be lost, as things reopen and return to normal. Against criticisms of the art world’s so-called knee jerk response to Covid-19 closures, I want to hold a space for such makeshift solutions.

Chris Hayes is a London-based writer.

[1] Morgan Quaintance, ‘Remote Viewing’, Art Monthly (June 2020).

[2] Brian Droitcour, ‘The Perils of Post-Internet Art’, Art in America, 29 October 2014.