1

Klubnacht, Berghain, Sunday, 12 May 2019

Deep down I know I am becoming a bird.

Deep down, as I dance on the podium under red spotlights in Berghain’s darkness and the techno’s clamour, I realise that, although still humanoid – albeit a human with disappearing fingers – I am becoming a bird.

I look down at my fingers; they no longer look like mine. Weirdly, they look like a painted portrait’s fingers. Extended, my painted fingers drip Pollock-like onto the podium floor. Arched out, my elbows are becoming wings.

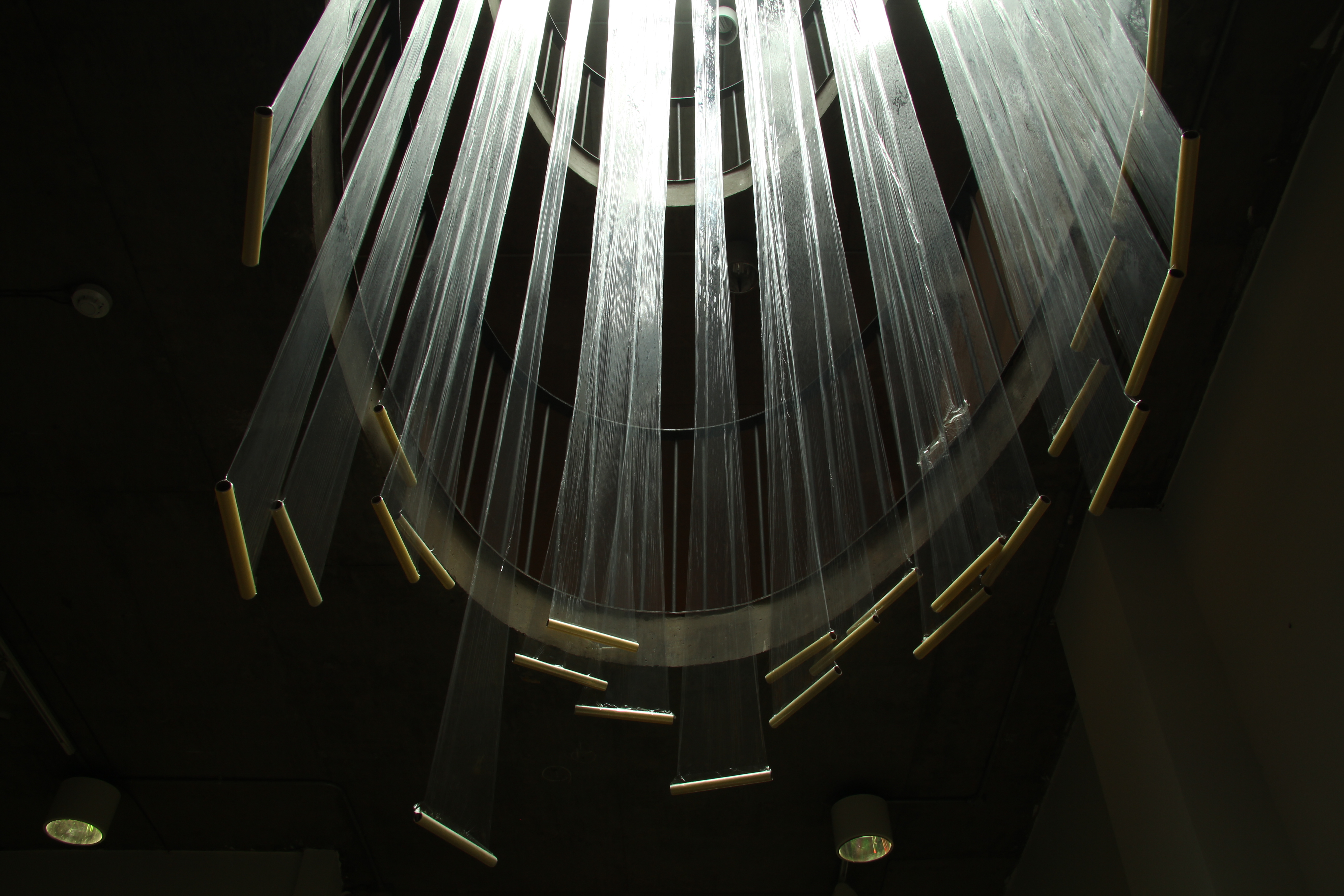

I gaze up into Berghain’s vault, its abysmal gloom. Spreading in tridents, blue lasers inscribe and erase blue lines. Far away in the distance, two large green dots hang motionless: a pair of monstrous green eyes.

My heart thumps and my shoulders oscillate. The venue is colossal, a world unto itself. And at the mercy of this venue, which, saturated by Rrose’s techno, is insatiably exploring me, I am becoming avian.

The music changes. From the surrounding speakers, deafeningly loud, comes a chorus of high-pitched shrieking.

This tinny high-pitched shrieking shifts my perspective. All around, as if we’ve suddenly been thrown into the blackest forest, the high-pitched shrieking and whirring – of cicadas, crickets, kingfishers – intensifies Berghain’s strange environment, intensifies my process of unbecoming.

Terror and excitement grip me. My fishnet top, a grid spanning my torso, curves in and twists like a vortex. My chest throbs; my fingers drool; feebly I try to keep dancing.

Beside me on the podium, also lit by red spotlights, a tall trans woman, in a bikini with a blonde ponytail, dances with exaggerated gestures. As she pirouettes elegantly before Rrose in the DJ box, I know that everything is as it has to be.

I realise I am no longer dancing but quivering, flapping, befitting the bird that I am becoming.

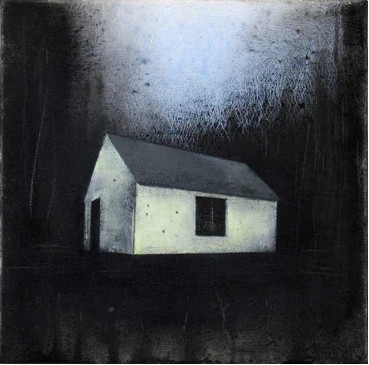

An image flashes in my mind’s eye: the Max Ernst painting I used to see at Tate Modern, Forest and Dove: a meek helpless bird scratched onto a forbidding dark background, a little dove drowning within a nightmarish forest.

•

I come to Berghain these days not only prepared for unbecoming but dying for unbecoming, dying to be explored by Berghain’s night, dying to burst from myself, dying to die while remaining alive. It’s an eminently philosophical urge, I tell myself, this urge towards undignified change. For wasn’t it Novalis – a Berghain patron saint – who said that philosophy begins with self-annihilation (Selbsttötung)?

I use the term ‘unbecoming’ freely for ‘becoming’. For me they signify the same thing: sloughing off your habitual self, your without-door form, through exposure to the natural force of influence exerted by another proximate body or phenomenon. Thus, through exposure to a tree, becoming-tree; to a cat, becoming-cat; to techno, becoming-techno.

The word unbecoming, however, has the advantage of stressing two important aspects of the process: 1) that the process of becoming-other implies a simultaneous process of unbecoming-yourself; and 2) that such an event cannot but be utterly unseemly, often embarrassingly so. Becoming-other is always completely unbecoming of you; it flies in the face of all that is proper, all shared standards of taste and reason, all social mores. What self-respecting person would want to invite over for dinner a giant jellyfish or dragonfly or mollusc?

Needless to say (I reflect, twitching my germinal wings), Berghain is nothing if not a platform for the trans-moral baseness of unbecoming.

But of course, such dissolution is hazardous.

•

Under the red spotlights, in Berghain’s heat, my mouth is dry. I open it wide – impossibly wide – and feel from my throat begin to emerge a beak. From my thick bare legs come two thin stalks. The stalks penetrate the paint-sodden podium. My painted fingers have by now oozed off completely.

I look over at Rrose in the DJ box. Rrose’s dark fringe, pale face, and lipstick are impassive; focused, she conjures from the black void of Berghain’s vault a torrential forest, all febrile shrieks and skittering pulses.

Below us on the gloomy dance floor, hundreds of bodies shift their slow thighs.

On this red-spotlit podium, my mind gushes with inky darkness. Into me pours the immersive forest; into me, the clamour of cicadas, crickets, dragonflies; into me, nightingales, larks, and kingfishers. They enter my body through my ears and eyes; they shriek and whir and flutter there, rupturing Berghain’s arboreal silence. Within me they shriek and whir and scream till all becomes dizzying.

It dawns on me: I’m not in fact becoming a bird; no, I’m becoming something else. But what?

•

I tried to explain this recently in broad daylight to Delphine, with whom I do a French-English conversation exchange. Delphine is a person of pragmatic temperament who works in spiritual therapy. Being French, she wasn’t incredulous. We were sitting in the sun at Ostkreuz eating ice cream, and I said that for me when the conditions are right in Berghain I become the music. This confused her. Delphine goes to silent discos in the woods at Müggelsee, where sometimes she and her friends put on their headphones, strip down, and dance. It’s therapeutic, she said. Delphine gave up drugs and alcohol recently after an acid flashback unspooled her sense of self.

When you lose yourself in this way and become something else, she asked, how can you relax? Isn’t it dangerous? How can you know who you still are? How can you be sure you will return to yourself?

My melting blue ice cream dripped on the concrete.

I just trust in it and submit completely, I said. Be beside myself.

In the Berghain main room, the music fills the space absolutely and you can enter into silence, a non-semantic zone. In the smoke and sporadic flashes, everything becomes eye-glance and pantomime. Everything is eyebrow, tattoo, nipple ring, fan, bandana. The visual is hieroglyphic. And in the dance floor silence created by this immersive music, with the lights swirling overhead, surrounded by outlandish pierced faces and BDSM costumes, when the music is just so you can overflow your bounds, traduce your outline, slip from your body, slip from yourself, and attain the physical sense of a beam of light, or a column of air, or whatever.

One Sunday a couple of weeks back, Physical Therapy, a young English DJ I like, was playing a set of driving, resonant-percussion techno, and under purple columns of light I managed to become a purple column of light. I was oscillating my shoulders and I focused on this big druid-like black man in front of me with robes and dayglow deadlocks, and I became a column of purple light – I unbecame in the music as a column of purple light.

•

So that’s what you do on Sundays? Delphine smirked.

It’s a holiday from myself.

•

Deep down I know I am mutating. As the high-pitched shrieking streams through my ears into my body, it dawns on me that I am, in fact, becoming-insect.

My mouth is not a beak but a mandible. My wings are not feathered but translucent. My wings are four, not two. My legs are not two but six.

Exploding on an arborescent drone, Rrose’s forest clamour shrieks all around as I shrink past the bird scale down into the insect scale, shrink down into the nervous twitching of a dragonfly.

I crane my insect head. Above in Berghain’s vault, a bright plane of blue has appeared. Tints of intense Klein blue thickly mat the vaulted gloom; it is an ecstasy of blue.

My agape dragonfly mouth becomes a blue void. I try to cry out; my mouth is just ecstatic blue space.

Exposed on the podium, I am now prey for the swirling kingfishers, sparrows, ravens, whose heads spin round and round me.

Everything becomes urgent.

2

Whatever its effect on me, whatever the hazards of unbecoming, I absolutely had to experience Rrose’s Sunday afternoon set at Berghain. Rrose is not simply one of today’s preeminent techno producers, artistically reinvigorating techno’s form as artists like Basic Channel did in the 1990s. And Rrose isn’t simply an excellent DJ, conjuring a forest of sound. Alongside these things, Rrose’s invented persona puts into play the conceit of personal identity.

Underground techno has always involved personas. Richard D. James is Aphex Twin; he’s also The Tuss, Polygon Window, AFX. Mike Banks is not only behind Underground Resistance but also The Martian and X-102. On a mundane level, the play of personas is not unlike a rock band and its side projects. But with some artists, like Rrose, it’s artistically instrumentalised. The self’s cryptic instability – the fact that we’re always obscure to ourselves – gives birth in techno to other selves, deviant selves, nighttime selves.

I spent a couple of years listening to Rrose’s techno before I paid much attention to her visual aesthetic and persona. When my friend David introduced me to Rrose’s music back in 2016, the hazy summer he and I lived in a dilapidated ex-Stasi building on the edge of Berlin, I was taken straight away with her processual techno, whose elegance on first impressions superficially reminded me of early Plastikman, but with more depth and scope. It was after Rrose’s music hooked me that I delved into Rrose’s persona.

That persona: dark hair, lipstick, painted nails; an allusion to Marcel Duchamp, who created a female alter ego Rrose Sélavy (a French homonym for Eros is life). Rrose is not a transgender woman but a man in drag. ‘Rrose is a persona, a political statement, an exploration of identity, meant to provide some magic in the performance space,’ Rrose has said. ‘A trans woman counts as a woman, I do not. But I hope my presence can be a small step towards more diversity and inclusion’. Through this poetic act of naming – a rose is a rose is a rose – Rrose stands in the DJ box as a focal figure, an index for conjuration. As she remarks of the club environment: ‘This is a parallel reality we’re in.’

Experiencing Rrose at Berghain is particularly fitting. What Berghain’s founders, Michael Teufele and Norbert Thormann, wanted to create with this boundless ex-power station space was a club as a work of art. Berghain is a safe space – albeit an insanely intense safe space – in which you should be free to do what you want and express yourself however you wish without constriction or persecution or shame.

Berghain builds on the heritage of underground gay clubs like New York’s the Mineshaft and the Saint and San Francisco’s Catacombs. In those clubs, Patrick Moore writes, ‘gay men in the 1970s took the radical step of removing the line between life and art, insisting that the performance not wait for the audience to arrive. […] This is the most complicated and exceptional kind of art that knows no boundaries and is driven by urges that are not fully understood, even to the artist’. [1] In the darkness of those gay clubs, external hierarchies dissolved. Similarly when you enter Berghain, passing under the Dionysian colossus, stepping onto the iron stairwell surrounded by fathomless concrete, your outside self undergoes Selbsttödung. Crossing the threshold involves shedding that mask, a liberation.

There’s no such thing as being there neutrally, I told Delphine. Everyone in the club affects the environment simply through being there. Everyone contributes. So, when I’m dancing in the main room I get off on exposure to all the strange faces and personas and costumes around me. You become intimate with those faces and personas and costumes, existing in each other’s zone for an hour, communicating non-semantically simply through being in a field of vision. And in that situation inevitably you have to ask yourself: What am I contributing?

The maritime-themed cover of Rrose’s EP Beware of Shells (2018) shows a crown of shells and pearls and coral set in front of a peach-beige orb on a white background. In the centre of the crown, above beaded rows of pearls, rests prominently a pink scallop shell inset with three crystals. At the top of the crown, five cerithium shells protrude upwards, their bases encrusted with silver balls, their whorls tapering in spirals towards pointed ends. The maritime crown’s colours – beige, purple, pink – enter your eyes as sickly sweet and unreal. There is something disturbing about this sea crown. It’s a coronation of the human; but it injects the human with the strangeness of the mineral subaqueous. It’s a becoming-inhuman of the human, achieved at the point of the human’s coronation. Like the music, it’s an exposure.

Beware of Shells’s music is highly refined in terms of production and composition. On the title track, a sound that at first seems industrial in character – a semi-quaver pulsation, its frequency envelope gradually filtered over background buzzing – at a certain point perceptually morphs into a sound biomorphic in character, the signal emitted by a living invertebrate. This is techno as expression of a postindustrial ruin; this is also techno as the sound environment of maritime life relentlessly proliferating. Eventually the music’s manifold layers, throbbing and clicking and pulsating, rise to a crescendo of collective excitement – a natural polyphony, free of any tonal centre – many-stranded seaweed and coral entangling in myriad patterns.

Within Rrose’s aesthetic, music and visuals align: quickening, outlandish, unbecoming. Techno and visual aesthetic and drag are consistent. RuPaul, when quizzed on his ‘real’ identity, says that regardless of whether he dresses male or female it’s all drag. Nor does he limit his identity to the human: ‘I am everything and nothing,’ he says, notably (not everyone and no one). Delphine said she hates techno because of how, in contrast to house music, which has emotion and soul, techno is anonymous and inhuman. I replied that I like techno precisely because it is anonymous and inhuman. For me it allows a radicalised Romanticism, re-arising in our Anthropocene conflagration.

Now to some it seems not worth the trouble to pursue the infinite divisions of nature, and moreover, they find it a dangerous undertaking without fruit or issue. Never can we find the smallest grain or the simplest fiber of a solid body, since all magnitude loses itself forwards and backwards in infinity, and the same applies to the varieties of bodies and forces; we encounter forever new species, new combinations, new phenomena, and so on to infinity…. The effort to fathom the giant mechanism is in itself a move towards the abyss, a beginning of madness: for every lure seems an expanding vortex, which soon takes full possession of the unfortunate and carries him away through a night of terrors. [2]

3

Exposed under red spotlights, the night in my veins, shrieking in my ears, I have slid right past becoming-bird into becoming-dragonfly. It couldn’t be more unbecoming.

The surrounding wildlife reacts. In this oleaginous gloom, the kingfishers, the cicadas and crickets, the bullfrogs, nightingales, larks and crows, hovering, shriek and whir, flap and stab, spinning and circling around my panicking becoming-dragonfly body.

Heartbeat racing, I am in danger. Nonetheless, although in this grotesque spectacle I am freaked and my four germinal wings twitch, what glamour!

Exposed to the Klein blue square far overhead, I feel a need to beat my four wings. But I’m paralysed. Assailed by these lark and crow and kingfisher heads, I feel the sweat drip into my enormous bug eyes.

By the DJ box I notice the woman. Now she has a massive orange beak. She is becoming-toucan. In profile she dances nimbly, slipping forwards and backwards to the beat. I tremble at her white toucan face, black toucan eye, protruding toucan beak seesawing and gesturing in mounting avian delirium. Is she readying to swoop?

But she is dancing to acclimatise to her terrain. The toucan lady in her bikini is becoming one with her new habitat. Her padding feet rattle the empty glass bottles by the wall. My four legs cling to the floor and my abdomen shoots out far out behind me; my eyes become enormous; my legs become multiplied and my diaphanous wings, viscid, unfurl, readying for flight.

My dragonfly mind knows I need to fly, to leave. It can’t be a coincidence that the dark vault overhead is brilliant with Klein blue. That blue is what I must seek. As the kingfishers and sparrows whirl around, as the toucan pads her feet, I focus my attention on the music.

Rrose’s music is a collective alarm, a solar beat, a sloshing sea-shore within the forest.

A serene delirium, the high-pitched shrieking continues. The beat pounds, carrying with it in my chest my anxious dragonfly heartbeat. Sweat stings my globular eyes. But now, as I enter the sound more and more, other sound figures appear. The insectoid shrieking, granular flow, and insistent pulse affect each other. They are inaudible forces wearing masks.

Now as I listen the insectoid swarm liquidates. The insistent pulse sweeps downwards: from the treble, where it was clacking pebbles, it sweeps down to the bass, where it becomes dull pounding on a loosely bound animal skin.

Within a second the insectoid shrieking drowns in filtered scummy tidal flow. The music shifts on.

The spell breaks.

Facing me, the toucan woman puts one hand on my shoulder. My six legs and four wings withdraw. My ears ring.

She smiles a toucan smile and says, Is this yours?

She holds the Rubik’s Cube I brought to the club. I always accessorise when I’m clubbing (rosary beads, action figures, juggling balls); I must have let the cube fall earlier.

I start coming back to myself. She smiles, slowly becoming a woman again.

All I can manage, kneeling on the podium, is to nod slowly.

•

Up in the Panorama Bar toilets, metallic doors clang. Reverberant voices echo. Snorts explode like gunpowder.

Sitting on a leather bench before the metal cubicle doors, I hold the Rubik’s cube. I warm my arm in a solitary shaft of sunlight entering the toilets through a window behind me. It is a hot day outside.

Before me the cubicle door bursts open and a man and woman tumble out. The girl is American, has blue hair, and is dressed in a green bathing suit with red socks and purple trainers. She steps into the beam of light and I withdraw my arm.

This light, where did it come from? Let me recharge. Jesus is real. Jesus is real.

Below her blue fringe, her sleepless eyes close. She holds a yoga pose in the light for all of five seconds before her eyes reopen and her mouth submits to amphetamine babble.

I have this place near my flat in Baumschulenweg – but wait, you’ve never been to my flat, have you? What’s your name again, Julian? Julio, right, I’m Sea Air. Yeah, Sea Air. Look at the colours I’m wearing, red and purple and green, I love matching. And look at my shoes, I spent too long in the sun and my blue shoes turned purple! And this lipstick, you know what it feels like? Blow jobs.

Around the corner, under the urinal trough, the pee slave hunkers. Topless and dressed in jeans, he looks up and pleads with his eyes. Eventually a man in a leather gimp mask obliges him.

Behind them rests an enormous amorphous lime green blob. The lime green blob turns its solitary lidless eye to me as, before it, the pee slave gratefully takes the gimp’s watery stream in his mouth.

How could you talk or write about this? How could you write these, at one with their nature and habitat, without violating or exploiting them? How could you relate this environment to others without becoming a male beast trampling the undergrowth, marking his territory?

Finished, the gimp zips up. The pee slave smiles, child-like in gratitude.

Danke dir!

Bitte sehr.

Notes

[1] Patrick Moore, Beyond Shame: Reclaiming the Abandoned History of Radical Gay Sexuality (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004), 13–14.

[2] Novalis, The Novices of Sais, trans. Ralph Mannheim (New York: Archipelago Books, 2005), 40–41.

Liam Cagney is a writer and musicologist with a PhD from City, University of London. He is the recipient of an Arts Council Literature Bursary and is currently writing a book set in the Berlin clubbing scene. ‘Rrose is Rrose is Rrose’ was originally published in PVA, vol. 11 (Winter 2019).