1 TEL AVIV TO RAMALLAH

What is the purpose of your visit? Passport control, Ben Gurion Airport, Tel Aviv. Late-night, slo-mo queuing. Everyone is being quizzed at a strange, unsettling length. The man in front of me – tediously chatty in our barely moving line – is now having his passport studied by a team of stern-faced staff. Eventually, he’s led away, taken for a special tête-à-tête. I’m a little worried for him – though he looks more bored than bothered – and, pathetically, I’m worried for myself. I’ve picked a bad-luck queue, a bad-mood passport booth. Stepping up, I’m all smiles: forcing good cheer with a put-on, tourist-eejit grin. There’s little need: the uniformed young woman doesn’t seem inclined to give a damn. What is the purpose of your visit? In the queue I’ve thought this through (with contradictory advice clashing in my head: Don’t lie about why you’re there – they’ll know; Just tell them you’re visiting Tel Aviv – don’t mention Ramallah). My answer is accurate, but vague. I’m here to visit an arts and culture foundation. No further details offered; no location given. The woman behind the glass flicks the passport shut and hands it back. Enjoy your visit. She’s done. I’m done. That’s that.

I’m here to visit an arts and culture foundation. Or rather: not here, not Tel Aviv, but Ramallah. I’ve never been here, or there, and in the car I’m too tired to quiz the driver about where we are and where we’re going. Still though, we talk. His name is Eyad and he lives in Jerusalem. He’s Palestinian but holds an Israeli passport. This will make the checkpoints easier – and why we can drive straight from the airport to Ramallah – though on the route we’re going, at this late hour, we’re not likely to be delayed. It’s dark outside, so I can’t see much but motorway. Yet after a while, as we pass through an armed checkpoint at the border of the West Bank, memories stir of night-time border crossings back in Ireland, slow-going as we hit the North on the way home from family holidays in the South: the presumed interruption in the long, dull drive from Dublin; the line of traffic up ahead; the inevitable interrogation; the terse, tense courtesy of my Dad’s tight-lipped responses; his quiet anger as the car moves on.

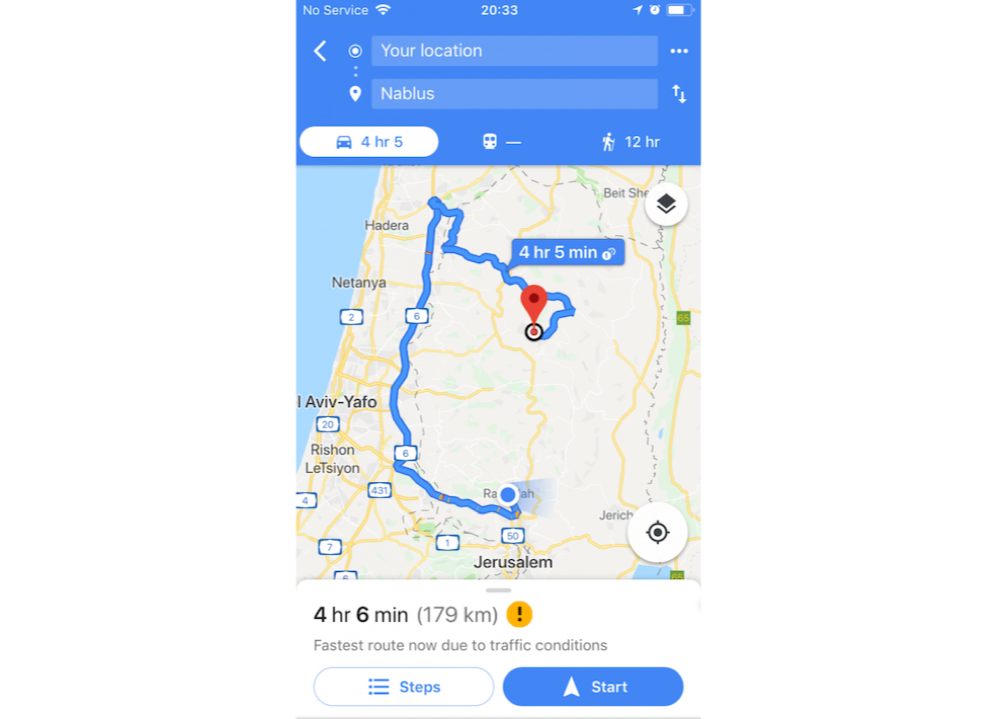

Over the next few days in Ramallah, there is a lot of talking, a lot of driving – and a lot of talking about driving. Everyone is on the move in complicated ways, or unable to move for complicated reasons. Time is tight during my visit, but I’m keen to move around too: eager to travel. On my one free morning, a day-trip to Nablus is proposed, so I check Google Maps for directions and distance. I’ve been told that Nablus is close, 30 km or so, and on my phone I can see a clearly defined route connecting here to there. But Google disagrees, advocating instead an absurdly circuitous, four-hour, 180 km trip along the Israeli side of the West Bank border. It seems that Google can’t, or won’t, make a direct connection between two destinations inside Palestinian territory. It’s as if the road from Ramallah isn’t real, or as if the real can’t be accessed. In any case, at the last minute, there’s a complication; the trip is off. We’re going nowhere.

‘Ramallah syndrome’ is the term used by artists/architects Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti to denote this city’s paradoxical social and spatial conditions: the ‘hallucination of normality’ that has become overwhelming in the absence of real political progress. [1] It’s a syndrome that seems, in some small ways, familiar. Susan McKay has written of how, during the Troubles in the North of Ireland, ‘there was […] a collective sense that if things were too horrific to contemplate they had better be ignored’; and with that necessary delusion came an ambiguous intensity. [2] (McKay recalls, rightly, the ‘demented energy’ of Belfast in the 1980s.) Late in the evening on the day of our cancelled out-of-town trip, one of our hosts takes us on a walk through what’s left of Ramallah’s old town; among many remaining marks from the violence of the Second Intifada (2000–5), there’s a wall-filling graffiti scrawl that seems to be a message from the city itself, a summary statement on the ‘syndrome’: ‘Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside.’

2 BETHLEHEM TO JERUSALEM

According to Google Maps, the distance between Bethlehem and Jerusalem is around 9 km. The predicted travel time – based on Google’s algorithmic data-crunching – is around thirty minutes. For such a short drive, one that might be unremarkable in many other cases, the expected speed seems slow: painfully so. Depending on who you are, of course, the pace of your potential progress could quicken, or become significantly slower still. This is a busy main thoroughfare – the Hebron Road – and like so many routes across this intricately fragmented and strategically segmented geography, it is interrupted by checkpoints: barriers where the meaning of ‘who you are’ is, in part, determined by where you’re from, or even, indeed, when you’re from. Possibilities for movement and passage depend on what type of passport or ID card you carry; and which version of these you hold in your constant possession is, unavoidably, an outcome of a complex, cruel history, a continuing effect of oppressive present-day politics and, fundamentally, a divisive product of the ways that those in power have placed you – the ways they have located and limited you – as a citizen or subject.

Here is a dispiriting, everyday example, one of many documented by Emily Jacir over fifteen years ago in her photo-text work Where We Come From (2000–3), and one of a million micro-incidents that might be easily overlooked among the multitude of frustrations, restrictions, and humiliations suffered by Palestinians on a routine basis. In 2002, the 9 km route between Bethlehem and Jerusalem could not be travelled by a man called Munir, whose humble wish it was to visit his mother’s grave on the day of her birthday. Born in Jerusalem but living in Bethlehem, Munir had sought to undertake a modest personal pilgrimage: paying tribute to his deceased mother, praying and laying flowers at her final place of rest. By any reasonable measure, this decent, apolitical act should have been no big deal. As the holder of a Palestinian passport and a West Bank ID (and as the son of parents exiled in the Nakba of 1948), Munir was, however, subject to the capricious constraints of state power and denied the right to cross from one neighbouring locality to another. On this occasion – as with, no doubt, so many others over subsequent years – Munir’s honourable family commitment could not be fulfilled. But even if, in such cases, certain borders can be crossed – official entry permits approved – the predicament for Palestinians wishing to make such standard, dutiful journeys – going from here to there and back again within the familiar settings of quotidian life – is intolerable. The practical impact of an anticipated checkpoint might change; the probable duration of a planned journey might be impossible to judge. As John Berger has written, ‘the effect of this on daily life is relentless. As soon as somebody one morning says to himself “I’ll go and see –” he has to stop short and check how many crossings and barriers the “outing” is likely to involve. The space of the simplest decisions is hobbled, with its foreleg tethered to its hind leg.’ [3]

Time, too, Berger says, becomes ‘hobbled’. Movement is fitfully impeded, disrupted with maddening unpredictability. Trips across negligible distances become drawn-out expeditions: ‘nobody knows how long it will take to get to work, to go and see Mother, to attend a class, to consult the doctor, nor having done these things, how long it will take to get back home’. Any sure sense of ‘temporal and spatial continuity’ is destroyed. And if they are maddening, these conditions must be deadening too: so much precious time given over to going nowhere. ‘For the most part,’ Edward Said once observed, ‘Palestinians wait: wait to get a permit, wait to get their papers stamped, wait to cross a line, wait to get a visa. Eons of wasted time, gone without a trace.’

3 DESPAIR TO WHERE

Emily Jacir’s Where We Come From is, among much else, a doubled-edged account of movement and stasis, a richly plural record of both relative freedom and severely imposed confinement. Across a series of small, evocative images and succinct accompanying statements, we are given glimpses of thirty Palestinian lives, each one acknowledging a different type of daily, highly localised limitation or traumatic, long-term separation. As the holder of an American passport, Jacir has been able to travel with more certainty and regularity than many fellow Palestinians: this identifying document affords her the flexibility to come and go both within and beyond her homeland. (It’s worth emphasising, of course, that such an entitlement should not be exceptional: it is a fundamental condition of individual liberty, enshrined in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.) Jacir’s US passport has empowered her to proceed past checkpoints, to cross borders with a degree of confidence. Movement is possible, if not straightforward – as no movement from place to place in Palestine is ever allowed to be. But Jacir’s travel credentials have also been valuable in enacting another, more expanded and collective, kind of access. Put to new use in the conception and realisation of Where We Come From – and presented as part of the completed artwork, alongside thirty-two photographs, thirty framed texts, and a single video – the passport provides, as Jacir has noted, a way to ‘access Palestine for Palestinians’. Her conceit has been to visit locations on behalf of others, to carry with her the requests, messages, prayers, desires, memories (and much more besides) of those who are prevented from making it to particular places themselves. Where We Come From captures a sequence of excursions, experiences, meetings, and observations; it reports back from trips that others can’t take, either because they are prohibited from entering the occupied Palestinian territories, or they are denied the everyday licence to move freely inside these controlled, carved-up, highly militarised landscapes.

Thus we meet Munir from Bethlehem, who asks Jacir to visit his mother’s grave. We meet Hana who lives in Houston, Texas, and has never been to Palestine, her wish being that Jacir might ‘go to Haifa and play soccer with the first Palestinian boy you see’. We meet Rizek, a student at Birzeit University in the West Bank; his hometown is Bayt Lahia, 80 km away in Gaza, and having left, he can’t return. After three years away – maybe the first three years of forever – his hope is that Jacir might call to meet his family and perhaps bring back a picture of his brother’s kids. Some such requests strike a poignant note. (From a man called Jihad, living in Ramallah: ‘Visit my mother, hug and kiss her and tell her that these are from her son. Visit the sea at sunset and smell it for me and walk a little bit.’). Others speak to the absurdity of life under extreme, fenced-in conditions. (From Mahmoud, living in Kufar Aqab: ‘Go to the Israeli post office in Jerusalem and pay my phone bill. I live in Area C … under full Israeli control, so my phone service is Israeli … I am forbidden from going to Jerusalem, so I am always looking for someone to go and pay my phone bill.’) Others again seek expressions of untroubled, uncomplicated existence, remembered or imagined: Marie Therese in New York asks Jacir to ‘do something on a normal day in Haifa’, making us wonder, surely, what a word like ‘normal’ might yet mean.

The stories recorded in Where We Come From – judiciously distilled as brief, explanatory notes and up-close, in-the-moment snapshots – are both divergent and consistent in their evocations of personal history and political reality. We see Palestine from multiple, plural perspectives, while gaining a strong, stirring sense of shared desire, shared disappointment, shared despair. From one angle, the collated ‘plurality’ of viewpoints has, perhaps, a disturbing dimension: Where We Come From demonstrates how extensively, and purposefully, the Palestinian people have been separated into diversely located and dislocated clusters; defined, segregated, and dispersed as disconnected groups. (Some are labelled and locked into a way of life by the colour-coded IDs that denote residency in Gaza, the West Bank, or Jerusalem; others have their identity – and liberty – partially determined by ownership of Israeli, Jordanian, or American passports). Yet the title and content of Where We Come From declare resistance to these fixed, enforced designations. Jacir’s work calls an anxious, urgent ‘we’ into provisional existence, just as, at the same time, it concentrates our attention on the diverse, under-represented details of individual Palestinian experience.

Declan Long is co-director of the Art in the Contemporary World postgraduate programme at NCAD, Dublin. His book Ghost-Haunted Land: Contemporary Art & Post-Troubles Northern Ireland was published in 2017 by Manchester University Press. ‘You Are neither Here nor There’ was originally published in PVA, vol. 10 (Spring 2019).

Notes

[1] For further information see ‘Ramallah Syndrome: Side Effects of a Post-Oslo Spatial Regime’, http://ramallahsyndrome.blogspot.com/.

[2] Susan McKay, Bear in Mind These Dead (London: Faber & Faber, 2008), 4–5.

[3] John Berger, ‘Stones (Palestine, June 2003)’, in Landscapes: John Berger on Art, ed. Tom Overton (London: Verso, 2016), 232.

[4] Edward Said, ‘Emily Jacir’, Grand Street, Vol. 72: Detours (Autumn 2003): 106.