Emerging from the Post-internet movement of the early 2000s, Alan Butler’s recent work explores digital worlds and the interdependence these idealised realities have with our own reality. Earlier this summer as part of IMMA’s As Above, So Below: Portals, Visions, Spirits & Mystics, an exhibition exploring spirituality in art, Butler displayed his film On Exactitude in Science, which was a frame-for-frame reproduction of Koyaanisqatsi – using the Grand Theft Auto (GTA) computer-game-series graphics – presented alongside Reggio’s original film. Over the last two years, Butler has also being engaging in a documentary photographic series within this computer-generated world, titled Down and Out in Los Santos. The following text is an excerpt from a conversation that took place between Butler and Aidan Kelly Murphy in the days following the opening of As Above, So Below.

Alan Butler

CORNER

Courtesy of the artist

Alan Butler: My work was always very comfortable in this warped, rainbow realm, looking at things that are almost a little stupid. As part of the criteria for my selection process I might ask, “Is that a bit of a shit joke – a slight wonk? Yes? Yoink!” I never liked the Post-internet title: it failed to describe the activity properly, because the topic is actually subjugation within data-capitalism. Post-Snowden, anyone making aesthetic Post-internet art really needs to take a look at themselves.[1] There are way more interesting and important things happening right now that fundamentally relate to our reality and how the next one hundred years are going to pan out.

We need to consider that the internet is the result of this huge ecological catastrophe and that it has caused the enslavement of millions of people to produce infrastructure that runs it all – just so we can have this argument about ‘what way does a dog wear his pants’. That should be the joy of life, but look at what we have to do to get that infrastructure. Everything from trolls, to Trump, to climate change is about late capitalism, and how we are implicit in everything wrong with it. The aesthetics of melty-hologram-coloured plastic goop on a gallery floor should be pretty down on our list of intellectual concerns right now.

Aidan Kelly Murphy: The keyboard warrior who goes online to complain about people not recycling is slightly hypocritical because of the metal used to make the box he or she uses as their platform, and the way other products like that are produced, has a huge impact on the environment. You have to balance all these things; acknowledge the full picture.

AB: Exactly. How much can you paralyse yourself along the way? I think if we’re being honest, browsing the internet is an immoral act. When you go down that route and start looking at absolutely everything, the only thing we can do that isn’t really an immoral act is to meditate – and I’m not capable of doing only that!

AKM: With the internet we also have this idea of the ‘dark web’. If I’m not on the dark web then everything I’m doing here is okay – all the horrible and illegal stuff is over there. I’m in the shallow end, snooping on people on social media, looking at images of celebrities’ hacked phones, and illegally downloading music.

AB: Evgeny Morozov wrote about how in the first round of uprisings during the Arab Spring we heard terms like the ‘Facebook revolution’ or the ‘Twitter revolution’.[2] People have these heroic notions about these platforms. In 2009, Hillary Clinton’s state department found out Twitter was due to be down for routine maintenance, and they asked Twitter to postpone it so Iranians could challenge their election. Eighteen months later, it was found out that there were only around 150 people using Twitter in Iran, and it had nothing to do with the revolution. But then to a certain audience, perhaps in the east, this portrays Twitter as a weapon of American imperialism towards the Middle East. So it’s hard to be a user of a social-networking platform and not be implicated in the geopolitics. Just look at the guy in the White House; he wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t for Twitter, so it’s all the dark web.

AKM: In 2005, Freaknomics foretold the era of fake news when it advised: ‘Information is the currency of the internet. As a medium, the internet is brilliantly efficient at shifting information from the hands of those who have it into the hands of those who do not […]. The internet has proven particularly fruitful for situations in which a face-to-face encounter with an expert might actually exacerbate the problem of asymmetric information – situations in which and expert uses his informational advantage to make us feel stupid or rushed or cheap or ignorable.’

AB: It’s like this scene in The Thick of It (the BBC comedy series). The main character, Malcolm Tucker (who is the government’s director of communications in the vein of the Blair government’s Alastair Campbell), hears that the expert they had gotten was going to go against their policy, and asks, ‘Who’s your expert? I’ll get you a proper expert, what do you want him to say?’ We think of the internet as just a mechanism, as if it’s an aside for ideology. It only happens when people touch it, and when they do it gets corrupted. The trickery of the semantics is that we are presented ‘Data’ with a capital D as if it this pure and flawless thing. But it’s very existence is ideological. It’s made to be so detailed and abundant that it can be used to describe any reality. Like most technologies, think of things like cars or Photoshop, Data is nothing until it’s used, and only when it’s used does it become something either for good, or as is generally the case, for bad.

AKM: It’s a weapon of sorts.

AB: A weapon? Maybe a prosthetic. Like in Aliens – the robot suit. Through techno-hyper individualism you can be a greater, more powerful version of yourself, which in some case means you’re just a bigger asshole. I don’t think there’s anything inherently good about the internet anymore, but it’s not as bad as we make it out to be. It’s not all a Pepe the Frog / Donald Trump world either. It’s not all lost yet, but it will be soon. Unless we decentralise it and host our own stuff from our own servers, which we run and own ourselves from our own houses, then someone is always going to exploit us. The fundamental problem is that it’s taken us thirty years to figure out that thing that if something’s free, then we are the ones being sold. Maybe we need to shift the way we look at social media, and perhaps we need to forgive ourselves for not being the hyper-productive success stories we are expected to be presented as.

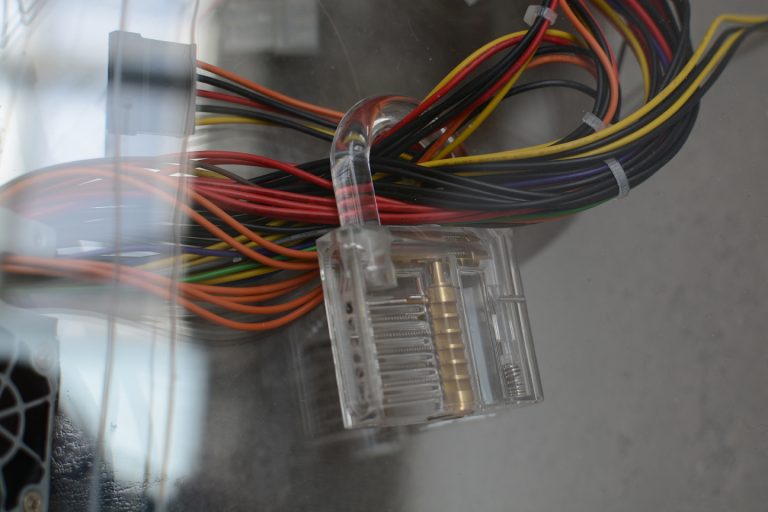

A lot of my work for the last ten years was based on that stuff, and that’s why I’m still very into coloured wires and grow houses, as seen in my recent show HELIOSYNTH at the Green on Red. It’s an infrastructure that’s an utterly visible way of presenting things without hiding the physical structure of how things are transmitted and move through space. In fact, I fetishise it because it’s the real subject. The content is just a component.

Twitter should end soon, Facebook should definitely go, and then Google as well. If we don’t replace them with something that we own ourselves, then we’re just perpetuating this idea that we’re all in a big shopping mall – somewhere like Singapore where people don’t have freedom of thought. You can walk around these public spaces that are privately owned, and everything looks nice and clean and you feel safe – but then nothing interesting is going to happen because you don’t have autonomy to live free and do whatever you want.

Alan Butler

Heliosynth

Installation view (2016)

Green on Red Gallery, Dublin

Courtesy of the artist and the Green on Red Gallery

AKM: Public space and urban planning, even when its goal is to improve life, is usually achieved by adding rigor, form, and control.

AB: Singapore has the same problem as Ireland: How do you deal with post-modernism when you didn’t really have the chance to have modernism? However, Singapore really made me feel that Ireland is probably one of the freest country you could probably live in the whole world. A lot of this notion has to do with how incompetent our authorities are. We don’t have the same income inequality as they do in America or Singapore, etc. In Singapore it is more compounded; they don’t have their own space. Six million people in a space the size of the greater Dublin area. They don’t have farms, so everything is brought in. Everything is like the IFSC: everyone lives in housing development blocks that have one entrance and one exit, so if there’s and trouble the authorities can shut it down – there’s no chance of dissent. It’s multicultural, but only because of the way people are housed next to each other in a benign but unnatural way. It’s like Sim City – they knocked it down and rebuilt it several times. Singapore works, but not really in terms of where the rest of the world has gone because it still exists as a disciplined society, and everything over here pretends to be all soft-core and post-modern.

AKM: Is it a place that is conducive to making art?

AB: There are loads of galleries, but for every show you put on you have to apply to the ministry for permission with a proposal saying what it is. There is a two-strike rule, and after a second time you offend someone, they’ll wind the business down. This breeds self-censorship of course. I was not used to it over there – was just mouthing off like and asshole. They didn’t want to hear it.

AKM: These days the internet is news about news; a cycle of repetition.

AB: It’s a procession of the real, the cycle of reproduction and re-versioning where the single, original artefact is obscured by the mode of transmission. It’s what Baudrillard was discussing – eventually everything will be the simulation of the simulation of the simulation to the point where we won’t know where the original came from, but then that doesn’t matter either because that’s not how we derive value any more. We’re only interested in the fifth-hand, wonky, warped version of things, because we are all the human embodiment of this re-versioning too. We are all just playing out our self-branded roles, pretending to be psychopaths on social media, so we can convince everyone else that we fit neatly somewhere into this society of achievement.

AKM: When discussing Koyaanisqatsi (1982), director Godfrey Reggio advises: ‘These films have never been about the effect of technology, of industry on people. It’s been that […] all of that exists within the host of technology. […] Technology has become as ubiquitous as the air we breathe.’ With that in mind and looking at your piece in IMMA’s As Above, So Below, you mirror Koyaanisqatsi with Grand Theft Auto V (2013), presenting them beside each other. Using this landscape as a base, how do you think they’ll play off each other, and is one more likely to influence the interpretation of the other?

AB: Ultimately, my initial premise was that anything that is happening here in the ‘real world’ is also happening in video games. Obviously, not in a very complex way, like the way real life can exist, but we are going there, we’re on that path to full simulation. Maybe all of our individual existences could live within there too, no matter what you do. There are all of these things that are there in Grand Theft Auto V that don’t have anything to do with the game narrative, and even characters we don’t play within the game – which was the focus of the Down and Out in Los Santos series: the homeless people.[3] They’re just there to make things look like our world. I think the that initial premise was to test to what extent the world has been replicated. I did want to try and find things to replicate. I’ve done that in a number of works. The Down and Out in Los Santos photographs are, I guess, more to do with replicating an approach, a genre, the modality of producing.

Alan Butler

PURPLES

Courtesy of the artist

AKM: Like a modern version of the Farmers Security Association (FSA)?[4]

AB: I was treating them as real homeless people. I wasn’t fully engaging with them and I was trying to keep my middle-class distance from them. But I treated them as sensitively as I would if I was a real photographer intruding on their lives. The Koyaanisqatsi/GTA V does something completely different as it is more about a visual and narrative replication of something. But in terms of the procession of things, basically being the simulation of the simulation. I’ve always seen Koyaanisqatsi as a beautiful portrait of planet Earth at the end of the twentieth century, and even today it still holds up as this amazing snapshot of glory and tragedy. The pace of it – I have literally seen the film frame by frame a thousand times at this point. I’ve seen things I wouldn’t have seen without taking this approach to making work, things appear to you at zero frames per second. I even found an AIB [Allied Irish Bank] in it. I intimately know that film, and I believe it is a perfect piece of art. There is nothing out of place. If I was the kind of artist that was into producing ‘perfect’, ‘beautiful’ things, that would be what I would aspire to do. Even though there is an internal narrative of, ‘Oh dear god, what have we become?’, we could give that film to an alien and say this is who we are.

AKM: Koyaanisqatsi, this is what we created, what we’ve achieved in the twentieth century – the age of Concorde. Now we’ve scaled back and that is GTA V. An ambient reality because we’ve fulfilled what we can fill in this world, so let’s create digital versions of the world that we can further expand into.

AB: Exactly. The title of the installation in As Above, So Below is not Koyaanisqatsi/GTA V, it’s On Exactitude in Science – a title taken from the Jorge Luis Borges’s short story, which is only a paragraph long. That in itself is a re-imagining of a Lewis Carroll text.[5] The story is essentially about this ancient civilisation that creates a 1:1 scale map of their territory so it covers the entire world they live in. Borges wrote it under a pseudonym and he dated it so it appeared to be written before the Carroll piece. My work joins the procession of re-versioning. I took the title of the Borges text, it was mentioned by Baudrillard of course, but it was essentially what I was doing here.

At the end of Koyaanisqatsi is a shot of the stock market, just before the scene of the space shuttle exploding. It prophetic, even in terms of where we are now. This leap into data-driven hyper-capitalism is the great unknown – danger was to lie ahead. I think we have this relationship with that being Irish means having the IMF debt over our heads. Seeing the stock market at the end, thirty seconds on from a body being picked up by paramedics off the street and being brought off to hospital – that’s where we are in Ireland, metaphorically and spiritually. Trying to recreate the Koyaanisqatsi world, with that sensitivity; I don’t think it’s possible yet in the virtual world but I had a pretty good go at doing it. You’ll see, this is eighty-six minutes and a good 90 percent of it is a pretty decent replication of the world depicted in the original. I did have to engage with the mod community,[6] if I needed a particular paint job of a United Airlines 747 plane, and sure enough someone had made it. Or maybe a fighter jet from the 1980s or ’70s – so when the credits roll, they’re still there but they’re just members of the mod community instead. That detail was intense. Making it was intense and required a closeness to the material that was in a way very real, despite the so-called virtual nature of video-game worlds.

AKM: Were there instances where a specific mod didn’t exist and you had to request one be made?

AB: I made my own mods. For instance, I once had to hack an existing mod in order to do some long-exposure photography. There were mods that would hack the camera, so I had to go into one of those and look at the code and reprogram things so the camera would pan from right to left over a twenty-five-minute period. There is bit of After Effects as well in terms of the long-exposure photography because it’s just not entirely possible within the game. I needed to use some post-production to construct the sensory experience that I wanted. Essentially, what After Effects was doing was replicating what Reggio was doing with the in-camera and process manipulation in the original film.

AKM: Some people don’t think that analogue manipulation is manipulation as it’s not ‘photoshopping’.

AB: Well in my thing, it definitely was! If there was manipulation in the original that gave me permission to replicate it as well. So tricks are tricks.

AKM: It’s a level of continuity. The manipulation you’ve brought to this is the same as Reggio and Fricke.[7]

AB: For the show in IMMA, Reggio has given me permission to use Koyaanisqatsi. My film has no audio, so I’m using the audio from the original. This piece is a presentation of both films put together. Further down the line, I’ll have to speak to him about what happens next. In a way it’s been a mad experiment, and I think it has kind of worked. I’ve sent him a copy but he’s on holiday. I want to talk to him about whether he wants to do something with it. He’s been so generous in giving me access to do this.

AKM: He’s quite ambivalent to requests, you were lucky – and I mean this with all due respect – that he didn’t tell you to fuck off.

AB: Totally. I wrote him an email and letter, and then rang him. He doesn’t really engage with the internet. He knew about the GTA series, and he said something like, ‘I think they did something like that already.’ He’s probably seen some of the older games, which I used as well. In my version of the film, I wasn’t able to recreate it all in just a single version of GTA, so I had to use all them in the end – which became more interesting as it’s the whole universe. For a certain scene, I needed arcade games and there were none in the newer ones so I had to go back Vice City, which is set in the 1980s.[8]

There’s a whole movement in Koyaanisqatsi, which was set in New York, that could not be replicated in the Los Angeles–style GTA V world. Inhabiting that pan-GTA universe, a weird thing happened when I got to GTA IV.[9] I hadn’t played that one before and thought, I’m going to have to play it properly to get to know it the landscapes and locations, and so on. About two days in, I got into this truck as part of one of the missions and the soundtrack to Koyaanisqatsi comes on. A total ‘whoa’ moment. So that’s what Reggio must have been talking about! I was at home, the lights were off, and thought, ‘This is insane!’ I do feel that there are these different levels of reality at play even in terms of making the piece itself. There’s the construct of the video game, the construct of the mods, and the construct of me manipulating the game environment to make it look like Reggio’s film. One of the most amazing things that makes Koyaanisqatsi such a powerful film is that it doesn’t follow a screenplay for a narrative; it’s more about what feels right to be looking at.

Alan Butler

On Exactitude in Science

Installation view (2017)

As Above, So Below: Portals, Visions, Spirits & Mystics

at Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Dublin

13 April–27 August 2017

Photo: Denis Mortell

Commissioned by IMMA, 2017

Courtesy of the artist

AKM: And the rest of As Above, So Below?

AB: It’s a blockbuster, but not sure what the art world will make of it. I’m sure they’ll have their own take on it, but for the general public there are lots of ‘wow’ moments.

AKM: You’ve been working on a new series titled Twenty-six Gasoline Stations, which takes homage from the Ed Ruscha book of the same name. Two things struck me when looking at this book: one was that it was reproduced twice in order to reduce the value of the book; and second was that it was initially rejected by the Library of Congress owing to its ‘unorthodox form and supposed lack of information’. So much of your work has to do with the transfer, the delivery, the mode of the message and information. What drew you to it in particular?

AB: One of the things was that the more and more I was beginning to engage in this in-game photography, the more I was realising that the California it was simulating wasn’t actually the real California but the photographic and cinematic history of California. Even the way things were, in terms of lens flare and colours. It’s Stephen Shore, Lee Friedlander, Ed Ruscha, and I kind of thought wouldn’t it be funny if I could find Twenty-six Gasoline Stations in GTA V, and it turned out there are exactly twenty-six gasoline stations in GTA V.

As well as that, I was listening to a podcast with Larry Clark and he was talking about photo-books in LA that were being produced at that time. A brilliant part of the story is that there was a 10 percent plus-or-minus law at the time for printing shops. The printers in California would always offer you 3,000 copies but give you 2,700. They were legally allowed give you 10 percent less than what you paid for – it looks like a great deal but you’re only getting 90 percent. I couldn’t find any evidence of this, but I fantasized about this idea of the edition; there’s supposed to be 3,000 out there apparently, but there’s probably not more like 2,700. [A link to the Twenty-six Gasoline Stations work is available here.—Ed.]

AKM: This plus-or-minus law for instance; it’s what a lot of your work talks about. You question the reality, you question the world in which that reality exists, and your approach is: I will question the matrix; I don’t need to question the data in the matrix, that’s the viewer’s job.

AB: Today I was in IMMA with one of the assistant curators looking at Hilma af Klint thinking this is the real deal. These things are literally priceless. And I said, it’s probably not an original is it? I’m only half-joking, because how do you know? How do you know some rich guy hasn’t had it swapped? You go to MoMA: Are they real Klimts? Are the Pollocks real? Are the Rothkos forgeries? We should assume that they are forgeries – we know the art world is the most unregulated, scrupulous fucking capital fantasy world you can imagine. But it doesn’t matter because it’s not how art works on the viewer. The real thing is a sleight of hand.

AKM: Should we approach a subject and should we believe before we are given evidence or should we disbelieve before we are given evidence as proof? As a society, we flick that switch depending on the situation.

AB: Do we need to know the truth? No, we don’t need to know the truth because maybe the fantasy is the thing that keeps us going as well. The thing about Twenty-six Gasoline Stations is that I’m in two minds about printing it. Maybe in my edition of 3,000 there are no copies. I’ll have printed money that will never be in circulation.

AKM: Don’t accept the information I’m giving you, use that as the basis to question information you receive in the outside world.

AB: That’s perfect, that’s what I’m getting at.

Aidan Kelly Murphy is a writer based in Dublin.

Alan Butler is an artist based in Dublin.

Notes

1. In 2013, former CIA employee and US Government contractor Edward Snowden copied and leaked classified information from the National Security Agency without authorization. These disclosures revealed numerous global-surveillance programs run in cooperation between American and European intelligence agencies and governments.

2. A US-based scholar of Belarusian descent whose works investigates the political and social implications of technology.

3. Grand Theft Auto V is a multi-platform game that replicates the world of Los Angeles and its surrounding county in the guise of the fictionalised Los Santos.

4. The FSA was founded in 1935 to help combat American poverty following the Great Depression. The FSA is most notably remembered for its highly influential photography series that it commission between 1935–44. The photographers chosen, which included Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks, have been credited with creating and curating the visual language of the Great Depression in the United States through images such as Evans’s portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs and Lange’s migrant mother portrait.

5. Borges’s piece was originally published in 1946 but was presented as an extract from a text dated from 1658 and Borges attributed it to ‘Suárez Miranda’. This fictionalised accreditation predates the influence for the piece, which was Lewis Carroll’s novel Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, which itself was released in 1899.

6. Short for Modification Community, this is an active online community where changes are made to games to adjust the look, feel, and context of a game. Modding in GTA is extremely popular and in the past has lead to issues for the game’s manufacturer Rockstar – most notably the Hot Coffee Mod. Here the hackers adjusted the game in order to allow players to play a new mini-game where they controlled one of main characters as he performed sexual acts on his girlfriend, after she invited him in for coffee. Further controversy arose over whether the mini-game was created by the hackers themselves or whether the simply revealed a hidden aspect built-in. The resulting backlash saw the game being reclassified as ‘adults only’, Rockstar being subjected to a number of civil action lawsuits totalling twenty million dollars, the introduction by Hillary Clinton of the Family Entertainment Protection Act, and ultimately a recall and reissuing of a new version of the game. This version was later hacked numerous times.

7. Fricke was the cinematographer, co-writer and co-editor on Koyaanisqatsi, and would later go on to direct the acclaimed films Chronos, Baraka, and Samsara.

8. Released in 2002, Vice City is set in a fictionalised version of Miami in 1986 and drew on heavy visual influence from movies such as Scarface and Carlito’s Way and TV shows such as Miami Vice.

9. GTA IV is set in Liberty City, a fictionalised version of New York City. This game was both set and released in 2008.