Chris: How does it work?

Steve: It’s simple.

He claps twice; loudly.

Apropos of Nothing

Installation view, 2015

Courtesy of the Artist

We’re standing in front of an applause sign in the middle of Steve Maher’s solo exhibition titled “The Melody Is the Message.” It’s a quiet Friday evening in LSAD’s church gallery. Most of the students have gone home, and the janitors hover around, waiting to lock up. The echo of the clap travels; the emptiness of the space and its scale is felt. In contrast to the busy opening night and how people performed to this piece in front of friends – selfies and the like – the sound of the echo now seems meek, tragic. An applause for no audience.

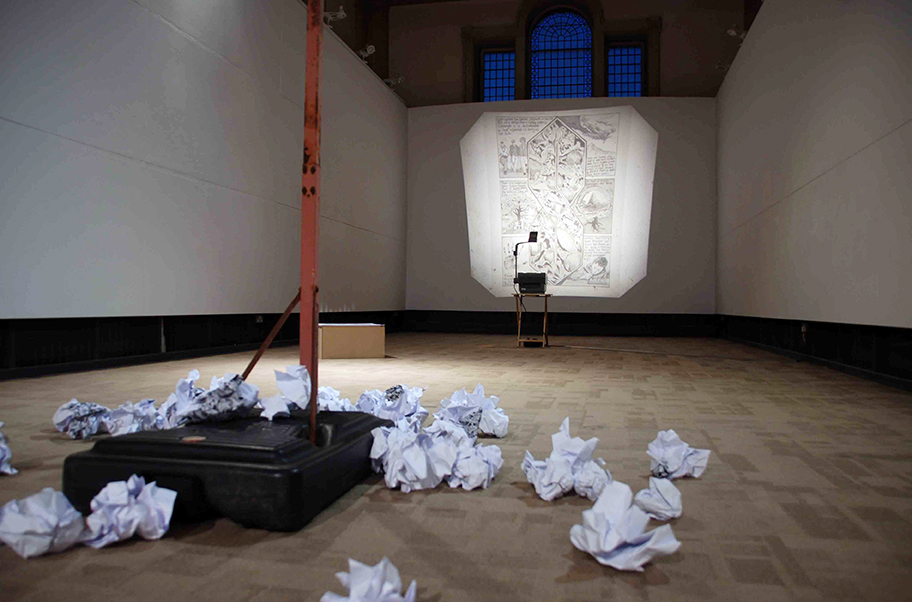

Apropos of Nothing (2015) is an applause sign placed on the floor. Like the majority of the elements of the artworks in the show, this is a manufactured object, heavily loaded with cultural meaning. Through clapping the viewer can turn the light of the sign on or off. This direct invitation to participate with the object also underscores the installation work Bedroomification (2015), in the east wing, sitting opposite Apropos of Nothing.[1] Bedroomification comprises a large-scale projection of one of Maher’s characteristic comic strips, a stack of posters, and a basketball hoop surrounded by scrunched-up balls of those same posters. The dynamic between the posters and the hoop is clear: take a poster, ball it up, and aim for the hoop. Both Apropos of Nothing and Bedroomification, despite being both different in appearance, use similar sculptural strategies through inviting the viewer to interact with the object directly – this playful relationship between the objects and audience becomes a form of metaphor for the kind of reading the audience is also invited to carry out. The artwork becomes cultural critique and political statement while revealing not only Maher’s humour but also his passion for music and its popular cultural objects.

Bedroomification

Installation view, 2015

Courtesy of the Artist

Throughout “The Melody Is the Message,” the references almost exclusively point to the post–World War II US “boomer” generation and in turn, the rise of the countercultural movement in the ’70s. This is particularly explicit in Excorporation (2015) that consists of a pair of non-descript blue jeans fitted onto a treadmill. As the treadmill runs the knees of the jeans draped over it become worn-out: the jeans might then appear authentically threadbare. With this Maher has constructed a crude machine that points to the coming-and-going of fashion trends in blue jeans over the years – from working class icon, to a symbol of counterculture, to the co-opting of this “look” by corporations. There’s a simplicity and directness about the message of this piece that also evokes nostalgic moments from my formative years. Because of the abundance of certain corporate quotations and countercultural residue, “The Melody Is Message” is substantially tied to a particular generation.

This thread is continued with qoSlIj DatIvjaj (2015), a looping nineteen-second clip displayed on a small box TV in the west wing of the space. The clip shows a scene from Star Trek where the crew of the Starship Enterprise sing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” in (the language of) Klingon to their Klingon colleague, Worf, who humorously rebukes them, saying ‘that was not a Klingon song’. Despite the simplicity of this piece, it feeds intelligently into the larger themes of the exhibition, one of which suggests the difficulty in even beginning to look at the artwork. For example to read, interpret, and engage in the layers of potential meanings in an artwork necessitates wading through layers of cultural reference, pastiche, and critique. Just as the blue jeans of Excorporation speak to a particular context, so too does this cult classic TV show.

I Hate Elvis

Installation view, 2015

Courtesy of the Artist

There’s a directness in how the artworks in the show are connected to moments within the historical arc referenced in the exhibition itself, from I Hate Elvis (2015), a large-scale replica of the badge Elvis’s infamous manager (Colonel Tom Parker) sold to protesters outside Elvis’s concerts, to 1985 (2015), a Teddy Ruxpin doll that reads out the testimonies of Frank Zappa, John Denver, and Dee Snider at the 1985 Supreme Court hearings on explicit content. There are coherent links between each artwork but within these frames of reference specificities of each piece are allowed to appear, which helps serve multiple levels of reading of the works, and this in turn generates a certain thickening, an opacity that moves the artworks beyond becoming mere comments on art, music, politics, and society. This ensemble of historic corporate and counter-cultural references builds a momentum throughout – pointing outwards, beyond the white cube.

Chris Hayes is an artist and writer based in Limerick. He is a co-director at Ormston House, and writes a weekly arts column for the Limerick Leader.

A link to updates and other writing from Chris here.

NOTES:

1. Here, east refers to the wing that is right of the altar in the standard cruciform church layout.