Aleana Egan’s output might be diagrammed as two parallel strands, each of which contains and reframes the other. In this proposed model, strand one comprises work that could be categorised as sculptural, including the ‘two and a half dimensional’ wall-mounted cardboard-and-filler works that have been a staple in her oeuvre for some time.[1] Strand two encompasses everything else: publications and films, occasionally produced collaboratively, found objects, and photographs. Strand one operates primarily in terms of its materiality and strand two in terms of its allusions to wider textual circuits. In reality of course, each contaminates the other. Materials suggest their own narratives, and cultural artefacts take physical form in various ways.

Aleana Egan

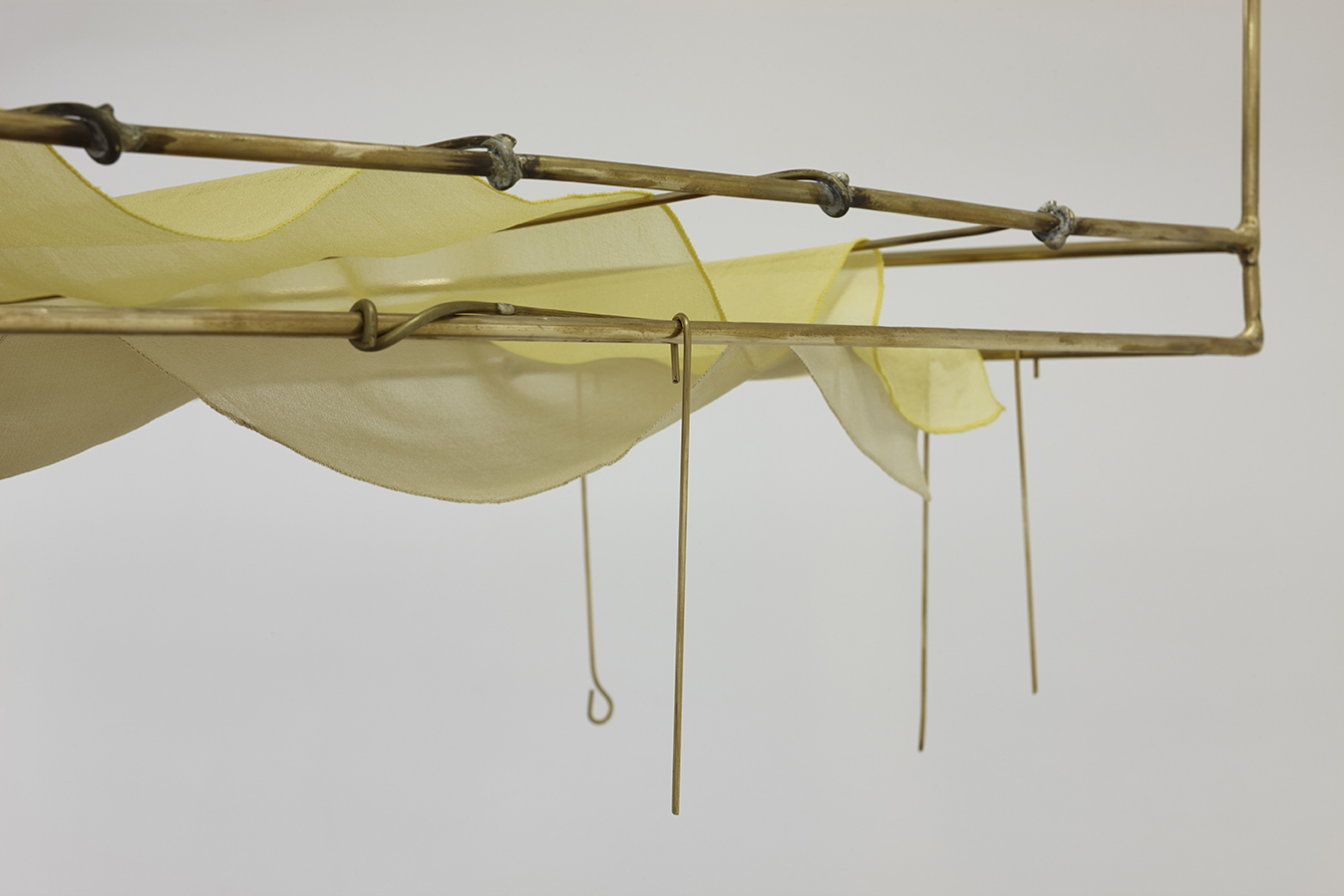

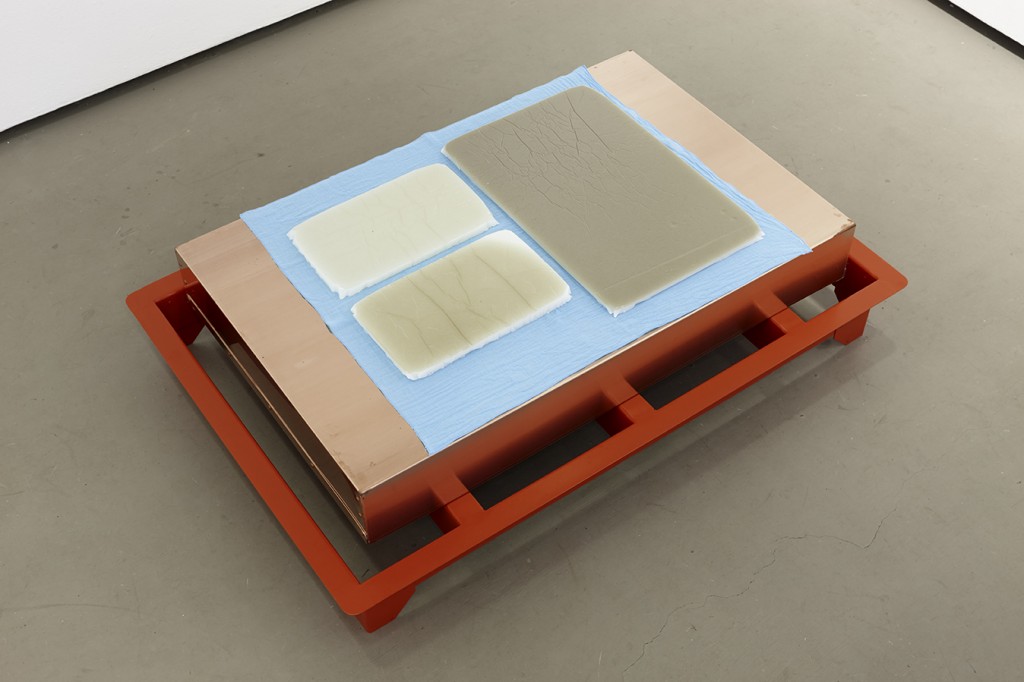

A friendly visit (2015)

Brass, copper, resin and sand, powder coated steel, dyed muslin, silk, wire

Courtesy of the artist and the Kerlin Gallery

Egan regularly invokes literary and cinematic references as agents of a kind of auto-curation. This has the effect of complicating any straightforwardly art-historical reading of her work’s seductive formal-material language. Associative strategies of this sort are the meat and potatoes of much contemporary art, but in Egan’s case, these wormholes into the world beyond the gallery walls indicate a desire to allow her objects to swim alongside us in a suspension of cultural references.

Over time, these framing devices have sketched out the envelope of a parallel universe of sorts, one populated by women, active, thoughtful, and often fuelled by a calm sense of purpose or a quiet anger. Explorers in this realm would tag it with metadata like ‘maritime’, ‘everyday’, ‘infrastructural’, ‘domestic’, and ‘feminism’. We are encouraged to consider her work from this specific place, which is a kind of no place, a kind of utopia. Here, momentary gestures are modelled for prolonged scrutiny, isolated architectural fragments take on communicative qualities, and time is frozen in the spaces between bodies, garments, and the built environment.

shapes from life, Egan’s 2015 show in Gallery 2 at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, presented a single sculpture placed in explicit dialogue with three other cultural objects: a painting, a movie, and the gallery itself. The Dressmaker, a painting by Margaret Clarke (RHA) on loan from the collection of the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork, hung on the gallery’s left-hand wall.[2] It was referenced in the curatorial material that accompanied the exhibition, along with Josef Mankiewicz’s 1949 movie A Letter to Three Wives.[3]

Like many of Egan’s conceptual anchors, both the painting and the movie relate to narratives centred on the experience of women. In Clarke’s work, two women occupy the centre of the canvas, the eponymous dressmaker on her knees focusing intently on her hands as she works to adjust some aspect of her client’s dress. The other woman standing facing her, gazing somewhat distractedly at the back of her own outstretched hand. It’s hard to tell whether she is concentrating on some detail or lost in thought. Her dress seems to have slipped off her shoulder in the course of the fitting, implying the latter. Fashionable fabric and pale skin form a radiant patch on a mix of matte murkiness – brown, dark red, and mustard.

Egan’s work often makes use of and refers to fabric, specifically clothing. For her 2012 show at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, titled day wears, she reimagined Gallery 1’s Brutalist non-cube with incredible sensitivity to its numerous nooks and complex sculptural geometry.[4] The ghosts of previous shows often resurface on subsequent visits to an exhibition space, and somewhat predictably I found myself reliving moments from day wears on my way through Gallery 1 to see shapes from life. These deliberately choreographed moments of spatio-temporal collapse are when the gallery’s programme is at its best.

Aleana Egan

A friendly visit (2015)

Brass, copper, resin and sand, powder coated steel, dyed muslin, silk, wire

Courtesy of the artist and the Kerlin Gallery

At a distance, Egan’s lone sculpture A friendly visit calls to mind a four-poster bed or a small altar. Circumnavigation is possible, but only just. Two clusters of objects – one stacked on the floor, one suspended from the ceiling – sandwich a thick gap of air. The base of the stack is a steel element, powder-coated a vibrant, sickly red. It has an outdoor feel, stable, purposeful, and precise, like a drain grating scaled to the dimensions of a coffee table. A cuboid, seemingly folded from a single thin sheet of copper, rests upon it. Its mode of assembly – tabs secured with copper pop-rivets – suggests an archive box enlarged to resemble a slightly unwieldy handle-less suitcase, but it’s more like an idea than a thing. The placement of this buttery, untreated metal on the pristine matte red steel unsettles, like an exposed live wire; memories from different parts of the body and brain collide, activating a complex wrongness. A rectangular turquoise cloth is centred on the upper surface of the copper box, slightly smaller than it and aligned with its edges. Upon it sits a trio of fleshy-grey resin slabs, each about the thickness of a thumb. Their arrangement suggests a large eyeshadow container, or a loose grid of images on a double-page spread, a lumpy book or periodical with a dyed muslin cover. The list of materials include ‘resin’ and ‘sand’, and their puddly forms index their former liquid state. The sand is ashen, the surface of the resin wax-like. Ash suspended in wax. For some reason I think of the skin on my grandmother’s elbows.

A pair of slim mild-steel rods, unlisted in the wall text, span across onto the tops of the gallery’s floating side walls. Suspended from these rods by a few dull lemon-coloured cords is a brass framework, trapezoidal in plan. Aspects of its structure suggest a kind of airing cupboard–oven hybrid. It houses two sheets of silk. These are hemmed – the upper one a subtle shade of lemon, the other murky like dust or fog. Both colours seem to be drawn from the patterned fabrics in Clarke’s painting over my left shoulder and they resonate like chromatic harmonics of the brass framework. In the company of these lemony browns, the bright colours at shin-height project a fierce energy.

The silks of the work’s upper section are cut to fit, roughly, into a pair of shelves, both of which resemble an upscaled grill-pan grid. Fabric droops in the gaps between the brass. Extending above these wavy planes, the rods, whose joints are loosely soldered and roughly sanded, sketch out the edges of a volume of air, reminiscent of one of Egan’s ‘metal- drawing’ sculptures.[5] Short lengths of thick brass wire, hand-bent into hooks and loops, pepper the framework’s circumference. Some connect the suspending cords to the frame, and others dangle from its lower edge in anticipation of some unspecified activity. They resemble a proprietary system for hanging curtains or pans, or something from a petite butcher’s shop.

The upper arrangement feels knitted together, as if there’s a desire to blend the materials into a single thought. Fabric and metal intermingle in a painterly synthesis. In contrast, the stack below is more of an arrangement of separate elements, in the manner of many of Egan’s recent sculptures. In this sense, they operate like language, like structured collections of words, each filtered by its placement in the ensemble but shadowed by its own meanings.[6]

Aleana Egan

A friendly visit (2015)

Brass, copper, resin and sand, powder coated steel, dyed muslin, silk, wire

Courtesy of the artist and the Kerlin Gallery

Gaston Bachelard speaks of cellars and attics in relation to the act of dreaming,[7] and, while A friendly visit does have a somatic quality, its form also alludes to another kind of upstairs downstairs. [8] This latent-gendered class narrative is implied through Egan’s reference-world. It is there in the relationship between Clarke’s subjects, their intimacy structured by the weight of professional protocols and histories, and enacted through quasi-ritualistic episodes of dressing and undressing. It is echoed in aspects of the plot of A Letter to Three Wives, a movie in which an episode in the lives of three women acts as the premise for an examination of economic mobility and the role that taste plays in social power dynamics. Interclass relations are central to its plot, which is structured as a series of flashbacks. In this context, the fact that Clarke’s spouse was Harry Clarke, a celebrated stained-glass artist and ‘leading figure in the Irish Arts and Crafts movement’, takes on a deeper significance.[9]

A few days after visiting the exhibition, I poked around online for A Letter to Three Wives. I bookmarked it on YouTube, but the user had been removed for copyright violation by the time I got around to watching it. Another search found it on Dailymotion. I streamed it, my mind partly in the movie-space, partly in my remembered version of the gallery. Initially, I tracked the story quite literally, keeping lookout for clues within the frame. But Egan’s modus seems to be less about the specifics of whatever curved-metal object rests in the background of a character’s bedroom and more about a wider and looser delta of associations, a reference-stream that forms its own flows of meaning around the work.

Over the course of the past decade or so, and at her own pace, Egan has evolved a dense, intelligent body of work with a potent materiality and a subtle but insistent politics. Each show nudges the centre of gravity, but palpably so. Materials and techniques are introduced or cast aside, scales shift and colour palettes are subjected to occasionally radical makeovers. These developments take place in the suburbs of a core vocabulary, which slowly mutates under their influence. In exhibitions, the work is often gathered into a bundle of timelines, placed among cultural reference points that resonate with and unfold its formal-material qualities. These points of reference are also treated as material. They are sculpted too. By hosting a single physical work among a cluster of these kinds of narratives, shapes from life generated a kind of meta-sculptural web, a deeply resonant oscillation between phenomenology and culture.

– Dennis McNulty is an artist based in Dublin.

REFERENCES

[1] This work often evokes the painting-sculpture hybrids of artists like Anne Truitt, Lydia Gifford, and more recently N. Dash, or, at times, the more architecturally inflected formalism of artists such as Thea Djordjadze.

[2] The designation RHA refers to membership of the Royal Hibernian Academy, an artist-led organisation that was founded by Royal Charter in the early 1800s while Ireland was still under British rule. More information here: http://www.rhagallery.ie/about/history/

[3] Reference was made to A Letter to Three Wives but it was not screened either in the space or as part of the gallery programme. Fruther information about the movie on IMDB can be found here: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0041587/.

Dimensions and medium for Clarke painting: Oil on board, 57 x 44.5cm

[4] Reviews of day wears include:

http://enclavereview.org/aleana-egan-day-wears/

http://seanosullivan.ie/egan/

[5] See also Declan Long’s description of Egan’s work in the Berlin Biennial here: http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/in-focus-aleana-egan/.

[6] Egan has occasionally been explicit about this relationship with language. See https://www.artsy.net/artwork/aleana-egan-lie-flat-in-the-sentence.

[7] See Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1958).

[8] Produced in the early 1970s, the TV show Upstairs Downstairs followed the lives of a wealthy British family and their servants. See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0066722/.

[9] Clarke was also a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Clarke.