1.

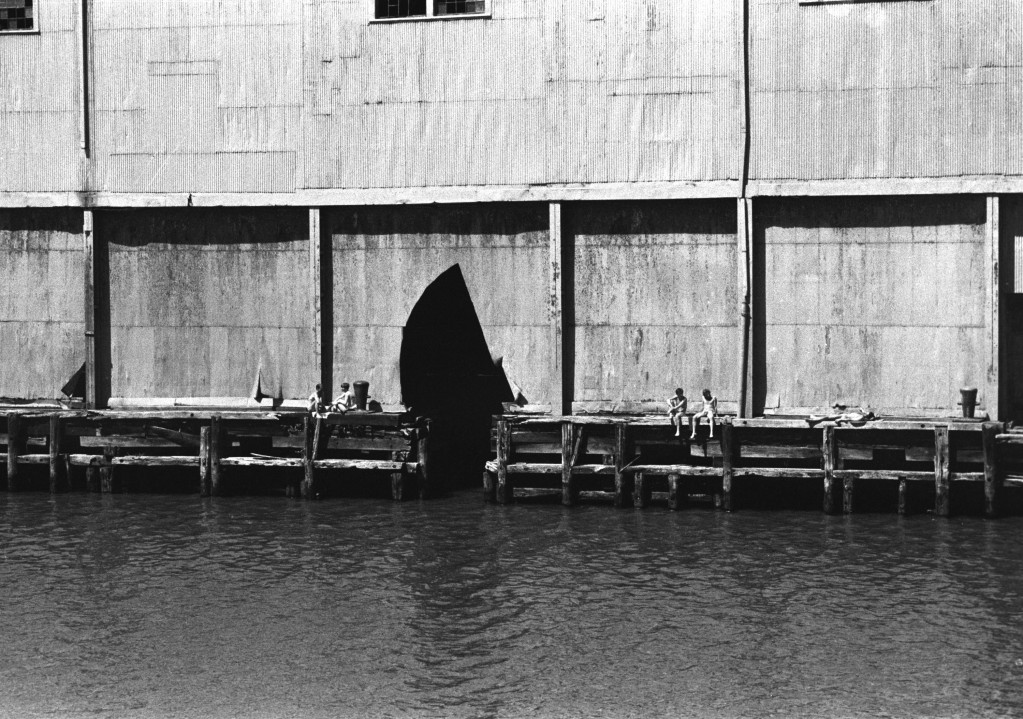

From 1975, for a period of a little over ten years, Alvin Baltrop photographed the underworld activities of the Piers, the stretch of then-undeveloped waterfront land on New York’s Lower West Side, close to where the new Whitney Museum now stands. The Piers were, at this time, deserted and largely unpoliced, becoming a hotspot for illegal activity – drug dealing, prostitution – and a haven for New York’s gay community. Baltrop’s photographs of half-naked, bare-arsed, or leather-clad men lounging by the water or posing under the piers themselves, have a sort of documentary objectivity to them, but their subjects are also imbued with an occasional balletic grace: a young homeless man in white briefs and sports socks standing casually at a kitchen table; an exchange between a proud young man in nothing but a waistcoat, backside exposed, and a laughing passerby; moments of contrivedly ‘casual’ public fellatio by the Hudson.

Alvin Baltrop

Untitled (Exterior of Pier 52 with four nudes), 1975–86

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1

Installation view (detail) of Greater New York, MoMA PS1

Photo: Pablo Enriquez

A selection of these photographs was arranged in one room on the ground floor of MoMA PS1. They are inescapably drenched with nostalgia, evoking a seedy, seemingly democratic stratum of New York before the corporate makeover of recent decades. More specifically, the period during which Baltrop undertook this deeply personal project was the period directly preceding the AIDS crisis, which wiped out a huge amount of the community he documented, destroying the carefree illicit camaraderie he had so exactingly captured, and leading to the eradication of the freedom of the Piers, which were torn down as sites of contagion during the hysteria of the pandemic that ensued. The presentation of these photographs seemed to indicate some nostalgia for a subculture, even if that subculture was defined by the prejudice, oppression, and menace its members suffered in the broader public arena. These photographs in this context suggested a peculiar longing, in fact: a desire for the countercultural cachet of the disenfranchised, a wish to recuperate a similarly subversive potential for the artist.

These and other such curious retroactive impulses were formative in the design of this year’s Greater New York, the large-scale survey exhibition that has taken place every five years since 2000 at PS1. In previous years, these shows were dedicated to the work of emerging artists from across the New York area; for the latest instalment, their work was joined by that of their more established peers. Hence Baltrop’s photographs (unappreciated during his lifetime, but increasingly acknowledged since his death in 2003) occupied a central chamber in one wing of the gallery, grounding a series of concomitant works arranged in the surrounding rooms. In one of these rooms, the activist collective fierce pussy (Nancy Brooks Brody, Zoe Leonard, Carrie Yamaoka, and Ms. Episalla) pasted bold text to one wall, outlining in simple, somewhat saccharine language the unrealised afterlives of those who have died of AIDS. (The same text was reproduced on a bundle of newspapers on the floor, to be taken away by gallery visitors.) With less sentimental symbolism, a series of five blue panels on the adjoining wall, the work of Donald Moffett, bore testament to the operation of hope. These panels, from a 1997 series of photographs of the New York sky, commemorate the coming to market of a new cocktail of HIV drugs that promised some respite from the previously inexorable onslaught of the disease: their bright affirmative azures are the simple statement of cautious optimism about the future. The bareness of their symbolism spares them the risk of poignancy – instead, they seem valiant.

Mira Dancy

Call from Violet, 2015

Neon

Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1

Installation view of Greater New York, MoMA PS1

Photo: Pablo Enriquez

In further rooms within this wing were works that responded to or extended the preoccupations of Baltrop’s work in different ways. Glenn Ligon, a celebrated African-American artist, exhibited five short wall texts, each a paragraph about one of the neighbourhoods in which he has lived over the past five and a half decades, the first being the Bronx, where he was born in 1960. With this simple conceit, he fashions a compelling and touching composite picture of New York, a city whose people are subject to the complicated operations of real-estate interests and the inescapable process of gentrification. Seth Price’s series Calendar Paintings (2003-04) appropriate imagery from a hodgepodge of sources; the four digital paintings exhibited combine canonical interwar American art and the blithely garish imprecision of outdated computer graphics illustrations, forming peculiar mediations upon the past and the mechanisms of its retention. Young artist Kevin Beasley’s Untitled (Harlem Matriarch II) (2015) is a beautifully evocative work, an assemblage of cotton dresses stitched together and encased to create a sort of enormous decorative plate, its richly coloured drum enveloping the viewer in a quiet, calm, semi-maternal embrace. The presence of Baltrop’s archival photographs at the heart of this cluster of work (and of course many of these works are by similarly well-established artists) guided the viewer gently through a set of preoccupations that felt like mapped coordinates: crisis and redevelopment, time and identity, home.

Other clusters of works seemed less easy to decipher – if indeed they are supposed to be deciphered at all. There were curated sequences on fantasy and economic exchange; on architecture; a further series of video and sculptural pieces addressed the interplay of fashion and visual art and asked questions about reproduction and mediation. There was also a room of figurative sculptures, a startling sight at first, though the arrangement didn’t ultimately really benefit the individual works themselves, which seemed herded together, becoming indistinguishable in the interests of a spectacular group effect. (Though Hayley Silverman’s miniatures – nestled, upon close inspection, in bowls of mushroom noodles or fried rice – provided a moment of unexpected comedy.) In another curated sequence on the third floor, Mira Dancy’s seedily monumental neon nude, Call From Violet (2015), provides a composed complement to her erratically energised wall paintings elsewhere in the gallery. Just beyond Dancy’s alluring neon figure, a work by renowned video artist Charles Atlas, Here She Is from the Waning of Justice (2015), features a long to-camera monologue about politics and peace by the iconic New York drag queen Lady Bunny. Her lengthy ad lib speech – on such topics as TTIP and climate change – is periodically interrupted, the audio stopping while the video continues to run, meaning that she is effectively silenced at intervals, a jarring authorial intervention that can’t help but suggest similar stage devices of Beckett’s (indicating maybe a common interest in the dynamics of authorial control). When at last the monologue ends, and Bunny performs a lip sync performance to a catchy jocular pop song, it feels both up-beat and also slightly uncomfortable, as if she has been drained of agency, coming to seem by the end like something of a comical marionette.

Ben Thorp Brown

Toymakers, 2014

HD video, color, sound, 13 min.

Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1

Installation view (detail) of Greater New York, MoMA PS1

Photo: Pablo Enriquez

Quieter and ultimately more resonant was a thirteen-minute video work by a young documentarian and artist Ben Thorp Brown. For Toymakers (2014), Thorp Brown spent a week following the work of white-coated workers at a ‘deal toy’ factory in Quebec, through the meticulous process of casting and decorating a batch of deal toys, a peculiar phenomenon contingent upon the excesses of international capital. These deal toys, exchanged when major billion-dollar trade deals or acquisitions are struck, look for all the world like traditional wooden toys for children (little houses in primary colours or trains with red wheels), but bearing extra plaques or panels or painted wooden blocks, branded with a corporate logos (Google, Deutsche Bank), proclaiming gargantuan sums of money. These toys are a notable peculiarity of a global financial system completely disconnected from everyday reality. However, it is the close attention of the artist to the careful, even tender, labour of the doll-makers, and to the materials of their trade (brushes, moulds, huge vats of white glue) that makes of the resulting video work – which might have been hectoring and univocal, given its subject matter – something disarmingly, compellingly complex.

This is what made the show, at its most successful moments, so impressive. In the hands of a seasoned curatorial team (Peter Eeley, Douglas Crimp, Thomas J. Lax, and Mia Locks), the localised concerns of these artists – fantasy capitalism; the competitive industry of city branding; the increasing dislocation of the urban poor; the nostalgia for subversion – connected confidently to the broader preoccupations of the western world. Perhaps this is natural in a city that operates in many ways as a sort of symbolic workshop or stage set or laboratory, even, at the forefront of the contemporary capitalist ecosystem. It is interesting, then, that such a pivotal survey show should this year be marked by retrogression; that the curatorial team’s sense of the ‘contemporary’ should be so openly backward-looking. This might be explained in a number of ways. It might be an attempt to complicate the category of the ‘emergent’, in light of a profession ravaged by precarity. It is likely also an attempt to differentiate Greater New York from other survey shows that have proliferated in recent years, all of which run the danger of becoming sheer commercial phenomena, in this case a frenzied trade fair for New York’s swollen and dysfunctional art market. The press material simply suggests that this year’s Greater New York was designed to examine ‘points of connection and tension between our desire for the new and nostalgia for that which it displaces’ [1], which is all fine and well, though it hardly seems to justify such a radical departure. Whatever the motivations for this curatorial decision, its effect was to limit the reverberations of new work, demarcating its boundaries, limiting its potential to be taken up and read in new ways. This is perhaps the price of the sheer confidence of this show’s curation. The work of younger artists here feels tempered, fenced in, by the past.

2.

No such limits were imposed upon the display of emerging art at the RHA in Dublin. Last year saw the end of the second five-year cycle of Futures, a series of annual exhibitions dedicated to the work of emerging Irish artists ‘around whom exists a growing critical and curatorial consensus’, as the press material has it. [2] Every year since 2011, a group of between four and seven artists has been selected to participate in the annual show. For the final show at the end of last year, as a culmination of the project, the majority of the previously participating artists (with one or two unexplained omissions) participated in a group ‘anthology’ show, most of them exhibiting in this instance a single work. The resulting exhibition featured twenty artists in two rooms (one large, one small); a strange mix of heterogonous styles, crammed unfortunately into a space unfit to accommodate it.

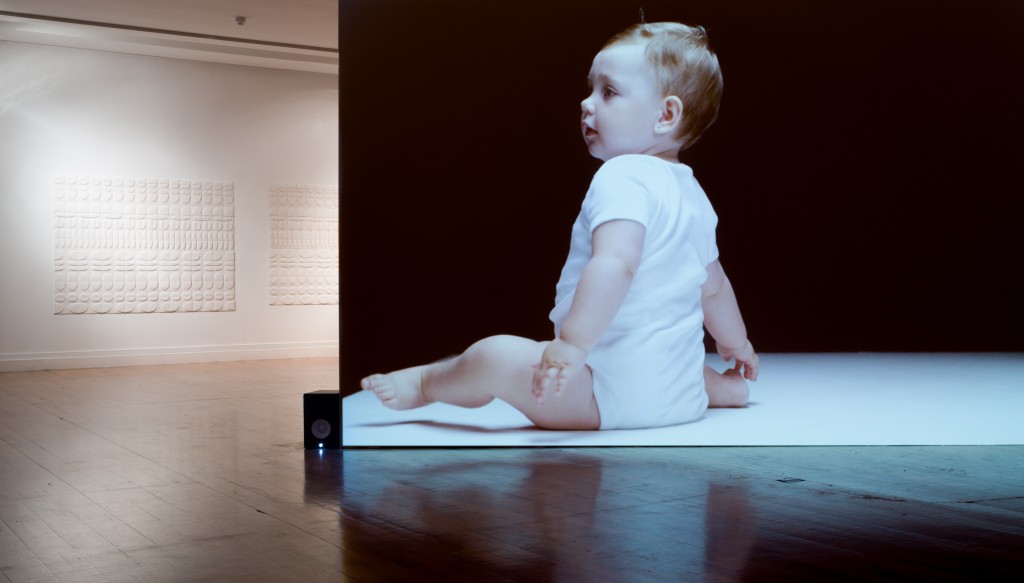

This was a shame, given the calibre of much of the work. (It should be said at this point that, for the individual Futures shows, 2011–14, each artist’s work was given much more space and individual curatorial attention.) Vera Klute’s white paper sculptures, of impossibly interwoven limbs, are a playful riposte to the Grecian figurative tradition. Maggie Madden’s two sculptural works incorporating optic fibre and telephone wire are thoughtful ephemeral interventions that somehow rose to meet the strictures of an unforgiving gallery space. Tracy Hanna exhibited four works, each of them a response to one of her follow exhibitors: Neil [Carroll], Adam [Gibney], Aoibheann [Greenan], and Eleanor [Duffin] (all 2015). These modest, considered, miniature works created fruitful echoes throughout the show, while at the same time forming a Tracy Hanna–shaped hole in the middle: a gesture with interesting and subtle repercussions. In the smaller of the two rooms, Jenny Brady’s video work, Going to the Mountain (2015), projected on a large freestanding screen, ushered viewers into a corner. Three babies feature in the film, recorded with extreme precision against blank backdrops and edited to create a kind of primal choreography. The audio overlay, a series of strange percussive noises, put me in mind of the soundtrack to Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood. The result is a thing of comic marvel, but also a kind of terror. The children are filmed without indulgence or pathos: with this simple gesture of defamiliarisation, Brady manages to foreground something of the awe and strangeness of human life.

Installation view of Futures Anthology

RHA, 2015

Courtesy of RHA

Photo: Mike Hannon

There was some more bombastic work on show also. Alan Butler’s Fixture (2013) was a case in point: an arrangement of children’s polyester T-shirts hanging in the middle of the gallery, on each a dye-printed image of the face of a politician: Enda Kenny, Bertie Aherne, Mary Harney, with the inclusion of former Deputy Director of the IMF, Ajai Chopra, indicating a context of austerity. This work felt pat, reductive, and lacking in reverberation, failing to do justice to the full, forcible assault of Butler’s previous output. Jim Ricks’s contribution operated on a similarly simple conceptual basis. The largest of Ricks’s three exhibited works, Carpet Bombing (2015), is a huge handmade rug, commissioned by the artist and collected from a carpet maker in Kabul, emblazoned with black logos representing a series of warplanes and drones, with names like Predator, Avenger, and Killer Bee. This declarative centrepiece had a commendable clarity – though for such an evidently politicised work, it was difficult to decipher any clear political statement. The carpet was accompanied by a video, Bush Bazaar (2015), documenting Ricks’s trip from Istanbul to Kabul to collect his purchase, intercut with scenes of Afghan life (dancers, market traders, congregants at mosques), from which I expected some probing of the work itself, some evidence of reflection or complication. What I didn’t expect was the inclusion of leaked iPhone footage of a mentally ill Afghan woman, Farkhunda Malikzada, being trampled to death by a cheering mob in Kabul, her body dragged to a riverbank and burnt. This horrific, extensive footage is presented to the viewer in silence. I could not help but ask why I was seeing it in such a context, particularly when elsewhere in the video Ricks either skirts dangerously close to the tone of a bemused foreigner, or overplays his hand with flashes of heavy-handed ‘commentary.’ (In the last frames of the video, he overlays handheld footage of drones, helicopters, and flags peppered with bulletholes, with the Mary Poppins number, ‘Lets Go Fly a Kite’.)

Still, Ricks’s bold, unequivocal work managed to withstand the rigours of the exhibition space. For more contemplative work, the crowded gallery felt uncongenial: Neil Carroll’s carefully energised geometric colour study – in blue, grey, mauve – on disintegrating canvas, plaster, and newsprint, Untitled (2015), is slightly lost in the clutter. Though small (the assembled materials roughly approximating a mid-size canvas), this work has a potential monumentality to it, effectively curtailed by the utilitarian curation of the show overall. Similarly, Emma Donaldson’s recalcitrant, faintly intestinal sculpture, Bone (2015), was in need of more room. These are works that would, it is obvious, repay amplification. More finely pitched to the needs of this show was Anita Delaney’s A Rat Biting Another Rat (2015), a rhapsodic and grotesque video work, with accompanying wall prints in which the bland nullities (and occasional legalese) of Internet communication is interwoven with an epileptic volley of club music (unfortunately its audio track was allowed to spill out over and spoil other works nearby) and images of rot, fatigue, collapse: a veritable onslaught that manages to provoke questions about authenticity, circulation, and ownership, without ever seeming to labour them.

Installation view of Futures Anthology

RHA, 2015

Courtesy of RHA

Photo: Mike Hannon

It is in the face of such sudden surprises as this that one sees the value of allowing the work of emerging artists to stand unsupported, without the context, as provided in PS1 this year of more established, august, proven work. The inclusion of such work provides a sort of institutional sanction, removing an element of risk, which ought surely to be retained in a show of this nature, allowing some work to fail, certainly, but enabling others to genuinely surprise the viewer. In spite of the few failures at the RHA, and the serious shortcomings of the gallery space, it is undeniably useful to see such a mass (or ‘compilation’, in the RHA’s rather try-hard formulation) of work by artists at critical early points in their careers, whose styles are still (for the most part) in development, collected in a single show. Such is the function of this sort of survey exhibition. Regrettably, Futures Anthology felt little more than functional. It gave the impression of a free-for-all, a series of compromises, contingent upon an unwillingness to really commit to the artists. (Are the artists supposed to just be thankful for being represented? That was the feeling.) A greater sense of generosity and care for the artists would have made this a much more rewarding exhibition, one that might have begun to do some justice to the vivid and occasionally vital work of the exhibitors.

– Nathan O’Donnell

Greater New York at MoMA PS1 runs from 11 October 2015 to 7 March 2016. Futures Anthology 2011–2014 took place from 18 November to 20 December 2015.