There is at this stage a long lineage of artist-led studio and gallery organisations in Ireland. Over the past two decades or so, organisations like Pallas Projects/Studios, Ormston House, The Joinery, Catalyst Arts, Occupy Space, 126, IMOCA, Basement Project, This is not a shop, Block T, and flat_pack have come and – some of them – gone. They have for the most part emerged out of discrete social clusters of recent graduates, looking to make some opportunity for themselves out of what has become a pretty dispiriting market for young artists.

Basic Space is the latest in this genealogy. Most of the artists involved are graduates from the Sculpture Department of NCAD in 2012. As students they received some good press for their occupation of a disused factory building on Thomas Street; they also held a series of conceptual, process-based exhibitions, including a Basic Space ‘shop’ in 2012 at the NCAD gallery, where they sold fragments of previous exhibitions (bits of gravel loosened in the installation of one site-specific piece, glitter that had been used in a performance), a light-heartedly brazen idea with a genuine if gentle punch.

Their new premises are a short walk through the Liberties, in Dublin 8, past blocks of post-war council housing stock as far as the Marrowbone Lane flats – probably the most striking of the apartment complexes produced during the 1930s social housing boom in Dublin. Basic Space is situated opposite this beautiful ship-like structure, on the ground floor of Dublin City Council’s Central Laboratory, Eblana House, built in 2006. These real estate particulars may seem superfluous, but Basic Space is an experiment in property and ownership as much as anything else.

Photo: Katie Mooney-Sheppard

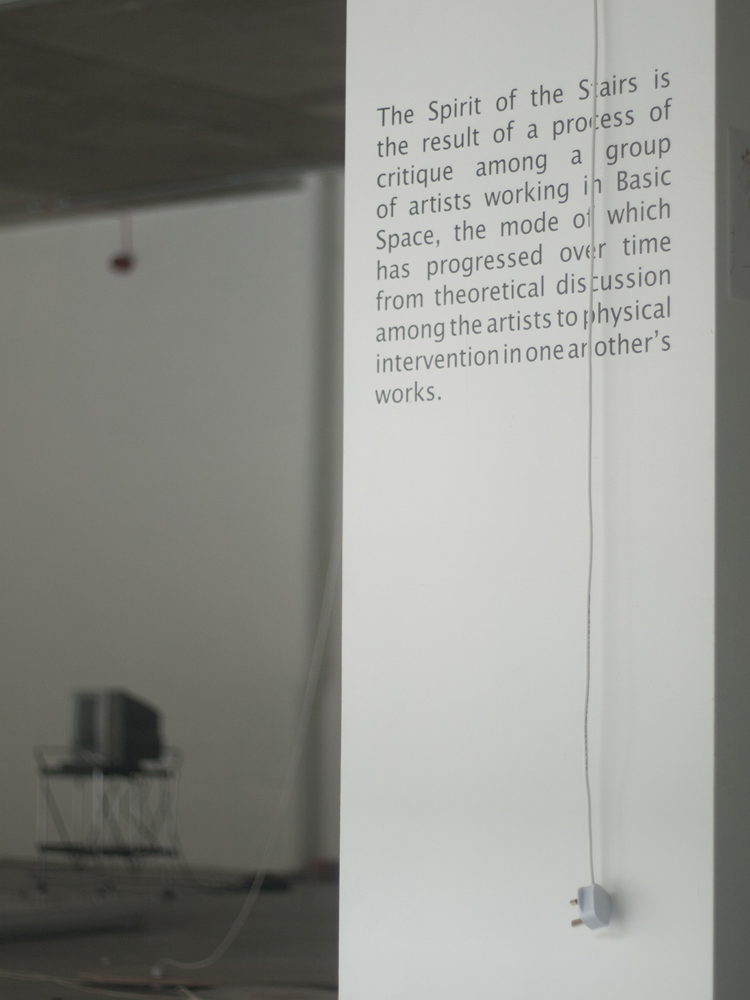

‘Spirit of the Stairs’ (a comic mistranslation of the phrase l’esprit de l’escalier) is a group exhibition by the studio artists who share this once vacant open-plan commercial unit. There are a number of sculpted clay slabs – like oversized flattened coins – dotted around the room, through one of which a string of hanging light bulbs has been threaded. The slabs are the work of Jane Fogarty, I think, though attribution of works is not altogether clear-cut, and what might seem singular objects are in fact threaded into and echoed across the exhibition. Fogarty’s work becomes one of a number of leitmotifs, recurring across the exhibition. On a large wooden structure, a lithograph of one of the slabs has been playfully stencilled. Another artist, Katie Mooney-Sheppard, has a number of plasterboard pieces which reflect and remodel Fogarty’s. On a small TV set, meanwhile, one of the studio artists, Clare Breen, with a jokey nod to the cookery show format, performs a demonstration of how the slabs were sculpted in the first place. The exhibition is founded on this playful idea of intermingling. Wires interpenetrate almost everything, supporting a system of lights interwoven into the exhibition as a whole. Nothing is attributed. By the door sits a stack of pages, featuring instead of a list of works a fragmented short story by Tracy Hanna. In the most striking of the exhibited works, a battered TV screens footage of the street nearby: two young girls from the Corporation flats approach, at first with a sort of aggressive inquisitiveness, though gradually they warm to the camera and the artist behind it, Eva Richardson McCrea. Then, in eerie silence, these two girls begin to perform a strange tentative dance. The camera lingers on them. This is a promising extension of the show, an intermingling with the working-class community beyond the building. It is the only sign of such interaction.

Photo: Katie Mooney-Sheppard

I am attending the show with a group of specially invited guests. Some of the members of Basic Space have welcomed us. They languidly occupy various positions around the room. It is a few days after their opening night, and they are here, they say, to initiate the ‘next stage’ of the exhibition.

Hannah Fitz, one of the founders of Basic Space, opens the conversation by explaining some of the details, demonstrating how creative decisions were reached. ‘We started formally, with weekly crits, but it became more informal. We wanted to make the process more open.’

Another of the directors, Daniel Tuomey, joins in. ‘We didn’t want tolerance,’ he says. ‘Tolerance is the most boring mode of cohabitation.’

Their discussion is a little fluffy. There is much use of the word ‘space.’ And the business-like hierarchy of directors and founders does seem somewhat at odds with the purported ethos – of a quasi-socialist or Marxist cohabitation of equals. Nevertheless, as a group, they are getting at something. Like any recent graduates, they want to engender some safe, structured environment within which to work – but they are also driven by a philosophical urge to interrogate and sunder this security.

Photo: Katie Mooney-Sheppard

That is the reason for the invite. They want us to assist in this process of disassembly. They want to open the exhibition ‘to the public.’ But are we really meant to believe that this hand-selected group of writers, curators, academics, students, and critics, represent ‘the public’?

Another visitor asks about their use of the word ‘independent.’ How ‘independent’ is Basic Space, in reality?

‘We do get an Arts Council grant,’ says Tuomey defensively. ‘But it’s tiny.’

And what about their dependence on Dublin City Council? They are leasing this place through the Council’s Vacant Spaces programme, which pairs unoccupied sites with small underfunded arts organisations on a temporary provisional basis.

‘Well, there isn’t much footfall around here,’ he says, indicating the deserted street outside. ‘So we’re hoping…’ He trails off. ‘We’re hoping we’ll be able to hold out longer than most.’

He is referring to the recent rises in property prices and rents which have led commentators to speculate about another housing bubble in Dublin. This is a throwaway remark, evidently unconsidered, but for me it constitutes the beating heart of this exhibition, and the reason Basic Space matters. The art works on display (with the notable exception of Richardson McCrea’s) seem a little inconsequential, all told, but in a way that is beside the point. As a market phenomenon, as a group of artists taking advantage of adverse economic conditions, Basic Space is verging on interesting territory. Can there be an ‘independent’ art – an art of continuous preparation – which resists both the gallery system and the property market?

Photo: Katie Mooney-Sheppard

This exhibition raises such questions, but doesn’t quite manage to provide any satisfactory answers. In a way, this assembly of invited critics and curators feels like the outcome of an entrepreneurial urge, as if Basic Space has simply acclimatised to the contingencies of a ravaged art market. You could argue they are just trying to make the best of a bad lot. But if I’m right – if this exhibition is actually setting out to disavow the careerism of the exhibiting artist – then the organisers have clearly hit a stumbling block along the way. Their radical aspirations have fused with a kind of disheartened pragmatism. Even the act of inviting us along to ‘advance’ the exhibition, rather than a broader public, strikes me, in this light, as a failure of nerve. But such, I suppose, are the exigencies of the hard up. And maybe I am asking too much of a group of young artists who have yet to gain a foothold in the industry.

‘What about ownership?’ asks another of the invited guests, a visiting critic on a residency in IMMA. ‘If somebody wants to buy a piece here, how do you negotiate that?’

There is a surprised silence amongst the artists. Eventually, it is Tuomey again who speaks up.

‘Nobody has ever tried to buy any of our work.’

Nathan O’Donnell