Although I know better, this exhibition has inspired in me a fanciful vision of Fiona Marron, circumnavigating Ireland in a little boat; TV and radio receiver pointed at the land, recording news reports and magazine shows. From these she chooses disparate items to weave together uncomfortable narratives, featuring the gross excesses of unfettered capitalism and greed. Every once in a while, she comes ashore, video camera on a tripod, held, resting on her shoulder. Silently, en plein air, she commits to disc, calm, moving images, which evocatively bear testament to her research.

The first time I saw Fiona Marron’s work, There was Truth in What They Said, I was confused. Good confused. I wasn’t sure the abandoned trading floor, revealed in a robotically smooth pan was computer generated or real. Several people I spoke to about it afterwards had the same quandary; fervent disagreements had broken out. It’s a question that is poised to become a key one in the future, as the digital world challenges our perceptions of reality. Within this work, I felt it was a triumphant matching of aesthetic form to context. The set was a closed financial exchange building interior, presented Ozymandias-like from its former power. Absence, abandonment, emptiness as well as varieties of silence feature heavily in Marron’s work. In Plenty of furniture, we see an elevated view of a warehouse, or industrial workshop perhaps? True to its titled promise, there are many tables, chairs etc piled up on view as well as a lone character, barely discernible. Marron often favoured mute silence in her videos, but there is audio here, just: Cagean rustlings seeming to anticipate an event we’ll never know. Sound is used suggestively in another previous work, Fend, which shows two fencers sparring in an empty space that looks as though it should house an open-plan office. Its most interesting moments are when the action forces its way out of the frame, temporarily leaving an adjudicator, dead centre, the lone figure on screen, his hands stoically clasped behind his back, as the foils clatter furiously against one another. In Caveat Emptor, Marron makes a (silent) turn, playing a solicitor representing the sellers of a salubrious property in an affluent Dublin suburb. A lengthy – though statedly abridged – list of legal preconditions is reeled off by the presiding auctioneer, who despite being a professional talker, stumbles over the gobbledygook legalese. More recently, in Construct #1.4 for Construct #1, at Monster Truck Gallery, her video loop of a falling tree was beautifully displayed as part of a successful marriage of sculpture and audio visual.

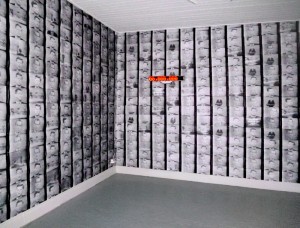

So to Last and First Men, the second installment of a five-part exhibition sequence Selected Stories in The Joinery, Dublin. The show was a snapshot of juggled ideas, interrelated, but frozen in time, leaving the viewer unsure of source or destination. The exhibition is populated by extraordinary characters, who pushed their names upon the world by the scope of their ambition, and greed. Marron’s main areas of interest abound here, high finance, the mechanics of trade, property and the question of verisimilitude. Entrance to the show was through the Joinery’s garage doors, which had been augmented with clear plastic strip curtains, such as are found across industrial loading bays, hinting at the exhibition’s econocentric concerns. In this room, the first part of the show’s title work consisted of a rear-projected video, shot by Marron in HD, seemed to serve as oblique visual touchstones to the exhibition. Here were ships, boats and their cargo holds; goalposts; hillside cave entrances; floodlights; a justice building; stadia and a lone living object: a horse grazing in front of a viaduct. These mostly panned images are displayed on a high screen, hung from the ceiling. The effect is enhanced uncomfortably by the projectors beam shining directly at you through the material and a subtle rumble piped into the space. In the next room, the viewer was surrounded by Bias Index, which comprises two walls covered with A4 screen-grabs of a 1960, televised debate between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy. The first of these four on-screen head-to-heads was a famous game changer for political electioneering, when it became apparent that the analysis of body language could be intrinsic to voters’ stances on candidates. So influential and divisive were these debates that most candidates refused to take part for another fourteen years.

Fiona Marron: Bias Index

inkjet print wall installation, 2011

Image courtesy the artist.

The work First and Last Men is continued here, in multiple, overlapping media. One could take a wireless headphone for a walk to (re)contextualise the visual elements. The audio contained snatches of archive news footage about ‘rogue trader’ Nick Leeson and Irish businessman Kevin McHugh. McHugh, who passed away from CJD in 2006, was responsible for Atlantic Dawn, the largest and most controversial fishing trawler in the world. Initially, McHugh was denied fishing rights for the vessel, until the then Fianna Fáil government stepped in to wrangle a deal for him, causing the European Commission to begin two court actions against Ireland. A private deal with the Mauritanian government allowed the ship fishing rights in their waters for nine months of the year, decimating the indigenous fishing industry. Marron puts the size of the Atlantic dawn in perspective by projecting an image of it over printed plans of Croke Park ‘and a half’ its oft-quoted match in terms of length. Leeson mostly speaks for himself, ruminating over his toppling of Barrings Bank and offering critical analysis of a finance industry seemingly unwilling to learn from its past failures. An LED ticker display on the wall, zoomed the figures (the precise significance of which, if any, were a mystery to me) 160,000,000 and 862,000,000 in red, past the viewer. A small TV (with headphones) on the floor replayed a BBC News report on the ‘mega-dairy’ of Cwrt Malle Farm in Wales where 1,800 cows are battery reared, prompting animal welfare concerns. In the rush to construct a slice of American-inspired agri-economic efficiency, the dairy’s sheds were built without planning permission.

Fiona Marron: Last and First Men

view of installation detail, 2011

Image courtesy the artist.

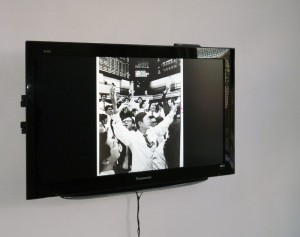

Keeping closely with the series’ fiction themed title, Father of the Futures connects the two loves of its subject, financier Leo Melamed: futures trading and science fiction. The flat-screen, wall-mounted video work comprises archive pictures, mainly of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, where Melamed was chairman from 1969-91, and snippets of biographical data on Melamed by an uncredited voiceover. It begins not with an account of his groundbreaking work in introducing computerised futures trading to the derivatives market, but how his moonlighting as a sci-fi writer inspired him to drive his vision of financial trading forward. With reference to his novel, The Tenth Planet, he pondered: “..if I could create a master computer that could run five planets, why can’t we create one damn electronic system that could run orders?” References to his fiction – published and unpublished – crop up again during the five or so minute piece, as it gives a potted chronicling of his moves to unfetter trading from the ‘open outcry’ of the trading floor’s exchange pits to a fully electronic system, such as his: Globex. There are sinister connotations to the complex systems of the futures market, perhaps seeming to the uninitiated like pure vagary, but Melamed is ultimately painted here as a sort of lucid dreamer, seeing himself as a Quixotesque character of determination. Is Melamed real? We are never led to believe we are seeing him in the images flashing up, and a possible significance of the narrator/author’s anonymity crops up – that the absence of source information could cast a shadow of doubt over the apparent documentary.

Fiona Marron: Fathers of the Future, archive digital image reel & audio

installation view, 2011

Image courtesy the artist.

The exhibition takes its name from Olaf Stappleton’s sprawling science fiction novel, charting aeons of humanity from the twentieth century on. Ostensively speculative fiction – its twentieth century ‘author’ is really the conduit for a history of man, telepathically transferred, by our furthest descendants – the eighteenth incarnation of humankind, two billion years in the future. Like the alien race in Melamed’s Tenth Planet, who find a Pioneer space probe* and set out in search of its origin, the exhibition (and title) also brought to mind Kim Deitch’s graphic novel, Shadowland, in which a character on an orbiting space station “watches scenes that were beamed telepathically from Earth…made over a period of ninety years and preserved on laser story chips”. If we were judged by an alien race on the basis of news reports speeding out through space from this planet, we might fare poorly, but one’s evil is another’s evolutionary necessity. Back on Earth, Last and First Men presented itself as an absorbing collection of interrelated stories, of individuals forging changes to society, decorated with Marron’s distinctive visual discourse.

Davey Moor is a curator, photographer and arts manager, based in Dublin. www.daveymoor.com

* Sent from Earth, complete with it’s return address calling card in the form of a plaque (with biological and astronomical information).

This review was first published on Paper’s Dublin Edition 1 in November 2011.