There used to be a massive, sprawling amusement park not far from where I used to live in Canada which only opened for four months of the year. The queues for rollercoasters could take up to two hours, but the thought of that stomach-turning and creaking, high-speed, two-fisted, double-looping, and tumbling ride of terror that lasted for five to seven minutes was worth all that. And then, that moment of complete stillness, that feeling of being upside-down, red-faced, and floating.

Gravity at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork looks at the work of twenty-nine artists who explore and interpret the physical forces of gravity either literally or metaphorically through painting, drawing, sculpture, and performance. It is a large show that spans over the three floors of the gallery and while there was plenty to see, there were a few that really stood out.

Grace Weir: Dust defying gravity

2003

16mm film on DVD, 4 minutes

Image courtesy the artist.

In the permanent Classical sculpture room, just beside the main entrance, Dorothy Cross’s video Ossicle (2008) and her large, impressive sculptural work Whale (2011) were presented in the company of ancient marble busts and statues. In Ossicle, a whalebone is rocked, the vibrating sound of the bone quickening until it becomes still. In the adjoining room, the skeleton of a whale is suspended like a historical relic over a rusty bucket filled with sea water. There is something both sad and majestic about the whale, removed from its natural surroundings like a fossil in a museum; a vacant reminder of what was once was living and moving in the sea.

Kitty Rogers’s Cacophony (2009) is a short video of the bells ringing at St Nicholas’s Colliagiate Church in Galway. There are ten bells at the church, cast at various times between 1590 and 1898. In Cacophony, the bells ring in a sequence, derived from a rubbing taken of the grating from the floor of the church (I learn later that the rubbings were done in pink crayon). Rogers figured out a permutation of numbers from the drawings and applied this to the different bell tones. As such, the decoration from the base of the church is translated into music, the resonating tones reaching up and over the city. This subtle and graceful extension of sound explores the relationship between nature and us, a symbolic gesture against physical forces and our own limitations.

On the second floor was Maud Cotter’s construction One way of containing air (1998) made of corrugated cardboard. The meticulous and carefully assembled structure appears solid and dense up close. From the front, the light from the window behind comes through the ridged pattern making it appear transparent and light in weight. The movement of the viewer is important to the piece, in a way, changing or completing the structure. The simple and organically-shaped structure subverts our expectations of the inherent physical properties of materials and objects. Similarly, Michael Warren’s Tall Stele I and II (1996) beside defies the viewer’s expectations. Two, thick planks of sycamore, one burnt, lean against the wall of the gallery and gently bend at the floor.

Aideen Barry: Vacuuming in a vacuum

2009

Sculptural object, 284 cm, plastic, rubber, fiberglass and silicone

Image courtesy the Crawford Art Gallery.

Last March, I was invited to attend a performance of Aideen Barry’s Flight folly at mother’s tankstation. After confirming my attendance, I received strict instructions to arrive promptly. On the night of the performance, Barry, dressed in a white, Marilyn Monroe-style dress with twenty toy helicoptors stitched to the edges of the meringue, held a remote control in her hands. Syncronised to the same frequency, the helicoptors lifted into the air, rattling and whirring together like an orchestra of bees. Across from photographs from the mother’s tankstation performance was Barry’s 2009 work Vacuuming in a vacuum, a film created in Zero Gravity that was filmed at the Kennedy Space Station (NASA). Both works (along with her Levitating video on the ground floor) play with ideas of weightlessness. The work demonstrates the potential for failure and that inevitable moment when things must come down. Barry transforms everyday materials into something absurd, playful, and distorted.

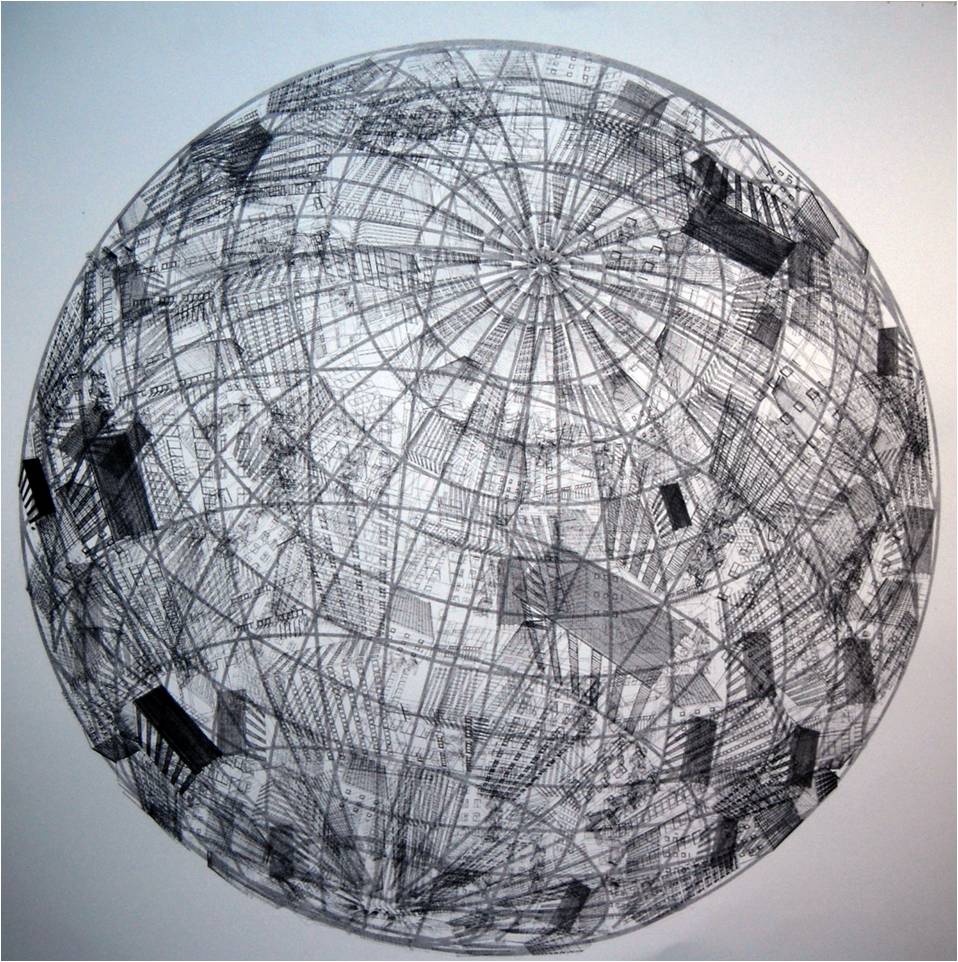

On the top floor, Grace Weir’s beautiful 16mm Dust defying gravity (2004) is a slow-moving meander through hazy rooms of Dunsink Observatory in Dublin. The camera moves through the building, peering over old books, antique telescopes and scientific instruments. As the camera moves over a model of the solar system, the dust in the air becomes visible, the small particles float past like a cluster of stars.

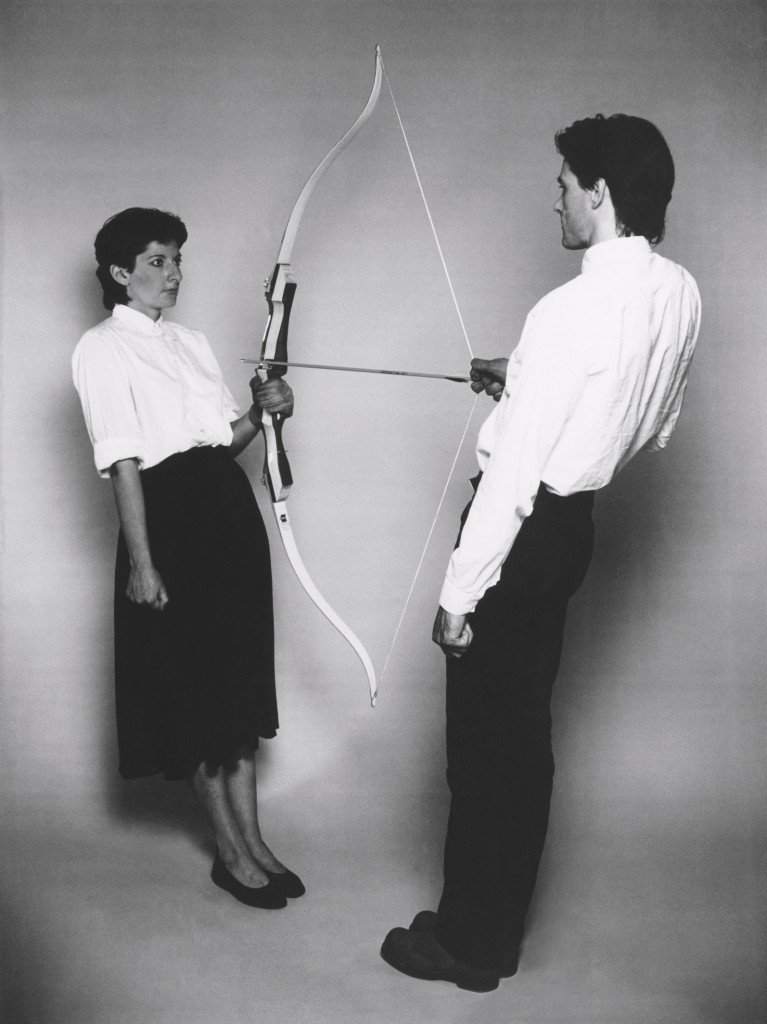

Marina Abramovic/Ulay: Rest Energy

duration: 4 mins, 10 sec

August, 1980

ROSC ’80, Dublin, visitors: 150 and Marina Abramovic

Courtesy Marina Abramovic archives and Lisson Gallery.

Beside is Yugoslav-born artist Marina Abramovic ’s 1980 performance Rest energy. The artist and her partner Ulay hold a bow and arrow taut with the arrow pointing at Abramovic’s heart, the weight of their bodies balanced and maintaining tension. A microphone recording of their heartbeats can be heard, accelerating as the video progressed. This unnerving performance of endurance extends to the hypnotic experience of the viewer as witness to these moments of danger. Such performance methods push the limitations of physical and mental potential. Suspension between audience and performer, between Ulay and Abramovic correspond to the natural forces of gravity.

Niamh Dunphy lives and works in Dublin.

*This review was first published in the Paper Visual Art Cork Edition last August during a two-week stay at the Guesthouse (Cork).