Curated by David Mabb and Mary-Ruth Walsh, Utopia Ltd. is currently on show in the Highlanes Gallery in Drogheda until the 3rd August. The show, previously exhibited at the Wexford Arts Centre earlier this year, is a visitation to Utopian discourse, drawing largely on the ideological context of late-nineteenth-century pastoral Utopianism, as well as Modernist and corporate models. The title is taken from George Bernard Shaw’s favorite Gilbert and Sullivan musical Utopia Limited. Shaw preferred the opera because it had no plot. The exhibition too struggles with an unwieldy plot unified by a strong theme: that of interference. Each art work seeks to usurp presumption and strongly questions the aesthetics of utopian visions, hence nothing is quite as it seems. The curatorial collaboration by artists to present an exhibition inclusive of their own work demonstrates an agenda to contextualise their own work with the work of others. It could be greeted as opportunist, but in fact demonstrates a sensibility to the accumulate a body of work reflective of their own concerns.

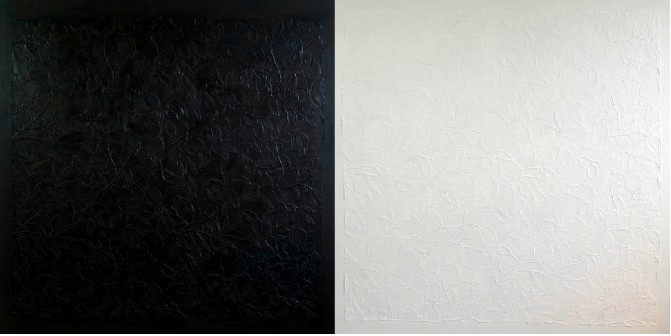

David Mabb: Two Squares (Morris Fruit Relief)

paint on fabric on mounted canvas

2009

Image courtesy of the artist.

David Mabb’s paintings demonstrate a control of surface, the thick, undulating texture of paint mimicks the tonal qualities of a William Morris fabric. Two squares (Morris fruit relief, 2009) marries the minimal colour of Kazimir Malevich’s white-and-black squares paintings, and Morris’s ornate renderings of nature. In Black square (Brer Rabbit) (2010), Mabb includes the selvedge fabric as a material clue – a source of provenance – that frames the black square in blue and white printed fabric. An aesthetic of design and pattern emerge from the symmetrical and thickly painted surface. Traces of colour peak through; a dim pink flower in Two squares (Morris fruit relief) softens the plane of white.

Mabb’s reworking of Morris’s fabrics, the subtle obliteration and reinvention of pattern, allows for Morris to be considered alongside the work of Malevich. The work of both men engaged with a unique sense of Utopianism. Morris’s idyll is seemingly bound up in agriculturalism and craft, however he also used this to describe the alienation of labour in industrial society. Malevich’s early influences included peasant embroidery. At the Second Modern Decorative Arts Exhibition in Moscow in the winter of 1917, he exhibited embroidered work. Charlotte Douglas describes Suprematist handwork in an essay titled “Suprematist Embroidered Ornament”:

“Just as in the paintings, the colored rectangles were meant to indicate an advanced consciousness of the universe or to be emblematic of an unseen world. Not only did the Suprematists aspire to make completely objectless painting, but they also immediately decided to remake the entire visual world in the Suprematist mode, an idea that after the Bolshevik revolution would acquire political significance.”[2]

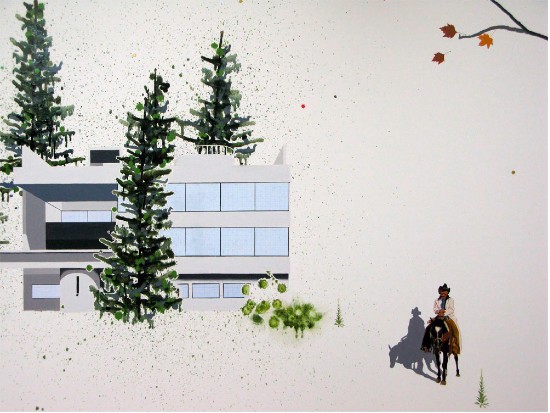

Blaise Drummond: La façade libre (Live forever in perfect health and happiness)

oil, acrylic, collage on canvas

2009

Image courtesy of the High Lane.

The white surface of Blaise Drummond’s La façade libre (Live forever in perfect health and happiness, 2009), interrupted by texture interspersed upon the primed canvas, speaks instantly of sparseness, separation, the found and unfound. A solitary cowboy moves across a landscape with a modernist building made of graph paper. The graphic-style fruit at the bottom seem to mock our appropriation of its wares. The splodges and splashes, the delicate moments of this painting, reflect upon nature’s strengths and weaknesses.

The artificial nature of our constructed space, in particular our communal space, is the subject of Lizi Sánchez’s sculptures. The drenching of faux marble and laminate surfaces with pompoms, gold ribbon and plastic pearls create whimsical structures that reflect upon artifice. The aesthetic construction of space is central to civil society and the flimsy nature of her construction is a calculated reflection upon the tacit nature of our civility. While the individual in Drummond’s La façade libre travels through a utopian dream, Sánchez‘s work describes the infrastructure of civil space through the adornment of that space, drawing attention to the construction of artificial environments that we live and work in.

Mary-Ruth Walsh’s photographs reflect upon the design practice of Eileen Gray as well as the dynamics of objecthood. They imply the ideal of modern domesticity – the clean, uncluttered lines and moulded shapes from sleek materials. The fact that these delicately constructed images are made with found packaging materials offers a reminder that designs are bought and sold, a commodity of our own desire for modern living. Gray paid particular attention to the public and private spheres in her architecture designs, while Walsh’s photographs seem to emphasise the edges of structures. Such attention to the boundaries of living implies that these boundaries might affect the way we live.

Similarly Brendan Earley’s drawings appear to take the nature of encroachment as a source. The hovering felt tip marks that redraw an invisible and unseen boundary are perhaps a manifestation of formal elements. This sense of formal design in making is clear in Workbench (2009). The aluminum cast polystyrene acquires the new weight of metal while still mimicking its own featherweight appearance. The aluminum cast and plasterboard are placed on the workbench in a cruciform arrangement. At once there is weight and substance, a formal plan but nothing is realised; it is all under construction but the art work is finished. Echoing Walsh’s interest in the way in which objects exist in a gallery or museum context, Workbench is placed on the alter. The Highlanes being a deconsecrated church has the added task of utilizing its inherited architecture.

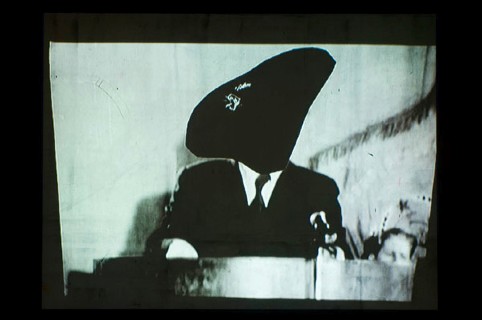

Pil and Galia Kollectiv. Co-operative explanatory capabilities in organizational design and personnel management

still, DVD, 2010

Image courtesy of the artists.

Co-operative explanatory capabilities in organizational design and personnel management (2010) is a slideshow presentation made by the Pil and Galia Kollectiv. It presents a fictional and bizarrely convincing account of a company whose sole operation is to place its employees under surveillance. The impact and relationship between output and creative labour, division of labour and collective labour were observed and recorded in statistical reports. The accompanying commentary describes the introduction of religious and ritual movements as a response to rumor and suspicion of surveillance which began to undermine the project. The still images, taken from documentation of an early computer company, are strung together and accompanied by an apparently reliable and trustworthy narrative, leaves you chilled by its believable nature.

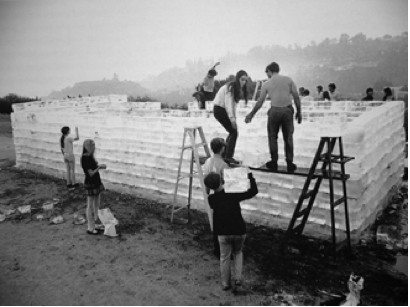

The series of films made by the Pil and Galia Kollectiv titled The future series imagines a future that evolves from an incident in Ikea in Edmonton, North London in 2005 where six thousand people turned up to avail of a limited special offer that resulted in a riot. The trilogy looks at the potential for a society to be born from such an event and seems reminiscent of the Wat Tyler Rebellion. The future for less (2006) imagines the birth of a totalitarian state as a result of a similar incident. In Better future, wolf-shaped (2008), we see the ritualistic cultish worship at the hands of hooded figures, and in the Future is now, a choreographed reenactment of the riot in Edmonton, sees the beginning of a popular uprising. The slightly neo-dadaist performance, the black-and-white costume, and allusion of social strata through caps and sleeve ruffles make the reenactment become like an orchestration of shapes on the gridded lines of the Ikea car park.

Utopia Ltd emphasises the notion of Utopia is that of inversion and transformation. That social constructs, political dialogues and ideologies can be turned inside out from what they seem to be, to what they potentially might be. Appropriation is a fundamental part of this show, serving to describe the impact of Utopian thought upon the actual material world.

Kitty Rogers is an artist who lives and works in Dublin.

___________

[1] John Bushe Jones. Theatre in Review. “Utopia, Limited.” Educational Theatre Journal. Vol.28. No. 1. March 1976.

[2] Charlotte Douglas. Suprematist embroidered ornament. Art Journal, Spring 1995 v54 n1 p42(4)