The press release for We are nowhere and it’s now sets the scene, so to speak, for a group show presenting eight international artists and their diverse interpretations of the concept of displacement. Theoretical clarification is given for the terms place and non-place to situate the curatorial investigation and to suggest the implication of social, political and personal issues. The exhibition is an attempt to recover something ‘lost’ and reminds me of the lyrics of the Bright Eyes song of the same title: “You see stars that clear have been dead for years/But the idea just lives on.” This review, the first of two parts, deals with the works of Elisa Caldana (IT), Barbara Hlali (DE), Khaled Barakeh (SY), Özlem Günyol & Mustafa Kunt (TR) and Marko Tadi?(HR), in Gallery 1 of Occupy Space. The bipartite structure will separate the philosophical filmic works of Dan Starling (US) and Sara Rajaei (IR) from the politically motivated works that highlight the intersection of ethics and aesthetics in socially engaged art practice.

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation view of Gallery 1, Occupy Space

Image courtesy the artist and Occupy Space.

On first entering the gallery, it is clear that the exhibition design is thoughtfully composed, slightly off-centre, elegantly balanced – ironically nothing looks out of place. The space could be a set for a Beckett play, a writer who is appropriately referred to in the press release:

“The cities and forests and beings were also without identity, they were shadows, they exerted neither pull nor goad…His being was without axis or contour, its centre everywhere and periphery nowhere.”

I am sometimes wary of exhibitions that refer to prominent Irish writers, borrowing from an established notoriety, but here Beckett’s oeuvre seems well chosen. When I search for the context of the quote in Dream of Fair to Middling Women [i], I find that a word has been omitted from the quote, which alters the meaning somewhat. Surprised at this discrepancy, I google the quote as it appears in the press release and find it used in a philosophical treatise on boredom. But the show is far from that.

In Gallery 1, six artists present five works in different media. Mounted flush to the gallery wall, Elisa Caldana presents three repeated photographs interrupted by an A3 page with the same photograph and text. A stack of these A3 documents is placed on the floor in front of the work, free for visitors to take away. A monument with no name is a photo-documentation of Tirana Square or more precisely a metal structure in Tirana Square, designed to cover the benches where immigrants would meet – a deterrent disguised as public sculpture. The photograph shows the square empty but for the geometric construction overlooked by a modernist building with drawn curtains and wonky blinds in the empty windows.

In the ‘hand-out,’ the artist explains that this square in her hometown in Italy had been a busy area in the city but is now a “peripheral” area. Once called “Resurgence” to commemorate the unification of the peninsula, the last ten years had seen the name changed through common usage to Tirana Square due to the presence of immigrants, mostly Albanian. Community tensions rose as “original inhabitants” began to fear this presence and reasoned by Morton’s Fork that if the immigrants were in the square, they were living off the state and if they were not in the square, they were stealing jobs. After a murder in broad daylight between Turkish relatives, the Army was called in to police the area daily and the structure installed by local residents. Reading Marx and Lefebvre, Caldana investigates the outcome of the failed strategies to resolve the underlying issues, with the architectural re-appropriation of “unusable” Tirana Square as its symbol. Although I question the artist’s idea of the gallery as a “neutral” space, the photo reproductions certainly de-contextualise the structure-object and undermine its power.

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation view of A monument with no name by Elisa Caldana

Image courtesy the artist and Occupy Space.

Next in the show is Barbara Hlali’s Painting paradise, an animation compiled of gouache on TV screen and video stills. Real footage of a city out of focus is overlaid with brightly coloured signifiers of a stereotypical Western expectation of the exotic East: palm trees, sandy beaches, lapping water, people wearing sunglasses. But the gouache layers are a thin veil of disguise, momentarily shifting to reveal a military presence, trucks, soldiers in fatigues, automatic guns. The paint strokes drag rhythmically over the succession of still images as though unable to keep up physically with the pretense. Through headphones I listen to a musical composition as soundtrack to the visuals but I no longer remember it; it did however hush the interior monologue as I watched the disturbing reality of some ‘other place.’ The artist’s tactics are effective in evoking the feeling of silliness, even shame at recognizing more readily the clichéd representations of holiday brochure-type images. The manipulation is intentional as the real footage is dull and faded, whereas the gouache layers are bright and vivid, communicating quickly to the eye. A cynical part of me might have thought I was desensitized to such imagery in light of the media coverage of the spreading chaos in the ‘Arab world,’ but the poor quality of the images, like some foggy nightmare, make me strain to make out what is going on, as though I am not understanding the full picture.

Ignoring the convention of the technician’s centre-point, the television monitor is placed on a plinth on its side. The viewing experience is somewhat uncomfortable and I sit on the floor. An explanatory note says that Hlali is applying the aesthetic cover-up used by the military to paint pretty landscapes on the walls surrounding the Shiite quarter in Baghdad. She questions whether “an aesthetic-artistic approach could meaningfully help to improve a situation (… and) whether military interferences can be the suitable means to achieve this goal.” In the closing frames, a brightly painted palm tree fades to reveal a dark silhouette of the tree and its fanned leaves. The image reminds me of the atomic mushroom.

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation image of Painting paradise by Barbara Hlali

Image courtesy the artist and Occupy Space.

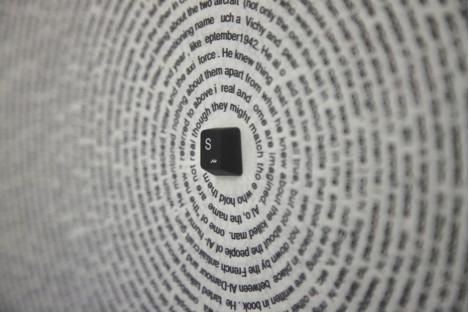

At the back of the gallery hangs Khaled Barakeh’s Syngamy, which looks from a distance like a target with a black bull’s-eye. On approaching the framed print, I see that text spirals in to the ‘S’ key of a computer keyboard. The artist’s statement explains that ‘S’ is “the only letter that shares its key with its Arabic sister phoneme.” (Syngamy, a biological term, is the fusion of two cells in reproduction; the conceit however extends beyond the shared key.) The text, a short story by Hasan Dawood, has been translated several times back and forth before arriving at this version. While I’m not familiar with the short story “Aluminium,” I do learn that Dawood is a noted writer in the Arabic world, conveying the disintegration and despair of post-war society. Like some optical illusion it is difficult to read the text and I get lost, but I do catch this:

“ o ilence la ted quite a time before omeone di rupted it by aying “what about the other ? What happened to them?”

The omission of the ‘S’ from the English translation is a significant gesture. The difficulty in reading the text becomes a successful if ambiguous communication through the subtext.

Addressed to the English-speaking world, the artwork motivates me to research the complex history and the current situation of the artist’s native Syria. During the run of the exhibition, Syria observed the 65th anniversary of Independence or Evacuation Day amid growing anti-regime protests. The government has been widely condemned for the use of excessive force to quell peaceful demonstrators seeking a democratic process in their country. The artist’s timing seems prophetic to me, but perhaps not to someone from the region.

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation image of Syngamy by Khaled Barakeh

Image courtesy the artist and Occupy Space.

Mirroring Barakeh’s whorl, Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt present a rope curled atop a plinth. Their collaborative practice, we are told, concentrates on the re-contextualisation of political signifiers such as flags, borders, anthems in order to “find new meanings and forms.” Here protest banners have been used to make a rope-like readymade sculpture with the written or drawn slogans concealed within; the painted or printed words barely leak colour through the twists in the linen material. When and where are the banners from and how did the artists come upon them? I imagine a public gathering, chanting in unison, the gestures of protest, some unknown cause or conflict. These images come too readily, and I empathise with the artists’ silent revolution.

The title of the work, however, could be a clue to the slogan, …And justice for all, the last four words of the Pledge of Allegiance. The original text, I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all [ii], has been adapted and adopted for a number of causes including human rights campaigns. The truncated end-clause has been used to title a Metallica album, a movie starring Al Pacino, a TV documentary directed by Michael Moore. There are posters available to download from US government-sponsored websites for citizens wishing to protest a particular issue. I doubt that these banners were originally used in the US or that another English speaking country would appropriate this slogan. I assume the slogan has been used in a non-English speaking country and this message was once again for the English-speaking world. But this is conjecture and perhaps not relevant to the statement that is being made in the gallery: art can be a useful device with a responsibility for reflecting on the realities of contemporary society and the state of global relationships. Re-imagining these objects “helps us collectively think beyond the relations and patterns that are typically and constantly imposed upon us.”[iii]

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation image of … And justice for all by Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt

Image courtesy the artist and Occupy Space.

The first of Marko Tadi?’s appropriated and reworked postcards is dated 13 XII 1978, the day before I was born, and as the postmark and message are obscured, this personal association makes me wonder where in the world did it come from and for whom was it intended. I think of Dérrida’s La Carte Postale that he was yet to write. And although the artist clearly states he feels no nostalgia for the found objects he uses in his practice, I am feeling a sense of nostalgia for handwritten letters and postcards instead of emails and text messages, and even for that time I don’t remember when everything was new. If the date had been different, most likely I wouldn’t have thought any of these things, but I enjoy the moment. Later on I figure out that the artist may have stamped the date himself; these documents could be forged.

A series of postcards rest on pins the length of the wall. The title of the suite is The second moon, a reference to claims, hypotheses and hoaxes about the discovery of another satellite orbiting the Earth. The artist has altered the historic images to varying degrees resulting in an old-school science fiction aesthetic. Using black, silver or gold paint and foil, he adds moons, transforms figures into floating metallic blobs, inserts geometric patterns, beheads a damsel’s suitor, quite often to comic effect. “I am very interested in imaginary/fictitious narrations,” says the artist “and possible changes of ‘past events.’” Indeed he acknowledges that these postcards are imbued with their own ‘emotional value’ and ‘historic context’, and creates new narrative structures, severing the imaginary possession of the past that is unreal [iv]. On his blog I see that the artist has individually titled his postcards, which adds a further dimension to their reading, but this does not appear in the list of works in the gallery: A daily scene, The ladder, Shapeless monument, The censorship of the second moon…

We are nowhere and it’s now

Installation image of The second moon by Marko Tadi

Image courtesy of the artist and Occupy Space.

The curators, Didem Yazici and Patrick Keaveney, communicate from the opening lines of the press release: “The exhibition seeks to map out in a series of works tenuous links and differing ideas of the displaced.” There are strong connections and contrasts between the artists, who tackle complex political issues with a sense of clarity and responsibility. There is a rhythm to the exhibition, with periods of intensity and philosophical pauses, which develops a narrative strategy between the works. Rather than feel a distance – geographical or emotional – I have engaged with the difficulties and continued to research beyond the scope of the transitory presentation in the gallery space. We are nowhere and it’s now was, for me, one of the most compelling shows to date in the ambitious and challenging programme delivered at Occupy Space, and this ‘review’ is but an entry point into the artists’ discussions. Having visited the exhibition on the birthday of Beckett, I return here to his words for conclusion: “To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now.”

Mary Conlon is a curator and writer based in Limerick.

________________

[i] The original typescript of Dream of Fair to Middling Women is located in Baker Library, Dartmouth College. Although it was Beckett’s first novel, written in Paris at 26, it wasn’t published until three years after his death, in 1992.

[ii] Penned by socialist, Francis Bellamy (1853-1931).

[iii] www.vesslartprojects.org

[iv] Sontag, Susan, On Photography, London: Penguin, 1979, p 9.