“Please raise your hands if you are from northern Africa.”

No response on the bus.

“I’m sure there was someone . . . Yes my darling, where are you from? Morocco? Can we please have a round of applause for our friend from northern Africa. We are happy to see you.”

Now a familiar character on the biennial circuit, Thierry Geoffroy (or rather, his alter ego Colonel) gathers data on a pressing matter. Dressed in safari gear, he embarks on a mission into hostile territories to track down an elusive creature. The biennial ‘motto’ has had several suspected sightings at Manifesta 8, but no conclusive evidence to confirm its existence… Using the tools of investigative journalism, Colonel conducts on-the-street reportage with the locals: “Do you know any Algerians?” he asks one woman. “Would you like to meet one?”

The Manifesta Foundation chose the Murcia region of Spain for its 8th edition of the nomadic European Biennial of Contemporary Art. Located at the southern edge of Europe, Manifesta 8 proposed that a dialogue with northern Africa would ensue. Colonel was not alone in his quest to dismantle this thematic approach. Overall, it was largely side-stepped and replaced with a more urgent set of questions: What is the nature of citizenship? What is the function of art? How does the media reflect and construct local and global realities?

Manifesta 8 proposed an innovative model for exhibition making, replacing the individual curatorial statement with a more discursive, collaborative inquiry, to reflect on the current burgeoning return of the group formation within art practice. Three curatorial collectives – Tranzit.org, Chamber of Public Secrets (C.P.S), and Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum (A.C.A.F) – carried out independent projects that shared contexts and had obvious points of intersection. Over one hundred artists displayed predominantly newly commissioned artworks across fourteen different venues, outdoor spaces, and media platforms.

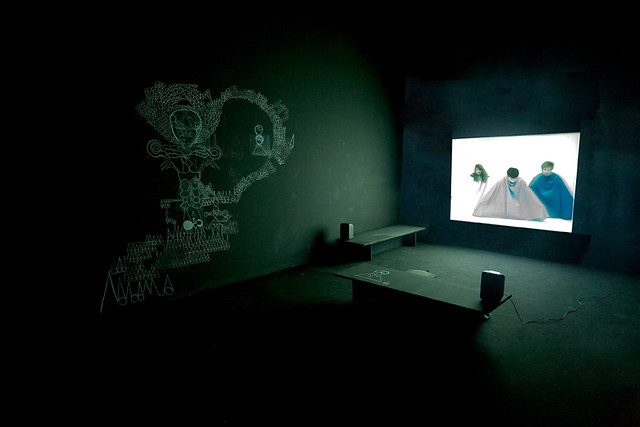

Sung Hwan Kim: Manahatas Dance, 2009

Pavilion 1, tranzit.org, Murcia, 2010

photo Ilya Rabinovich

The outcome of this collective curatorial model produced complexity which was often challenging to track, but this network of inter-connected relationships allowed for a transparency of evolving relational encounters; conversations, broadcasts, critiques, think-tanks, interviews, along with audience participation. Dialogue was very much on display, functioning both as a methodology and as an archive of process.

Employing institutional critique to question existing models and routine conventions, Tranzit.org formulated a ‘Constitution for Temporary Display.’ Critiquing the biennial “spectacularisation of culture” and the dichotomy between local and global, Tranzit.org worked collaboratively with artists to forge new ways for diverse narratives to co-exist within the ephemeral exhibition space. The dominance of site-specifity provoked a reflection on human histories within a particular location, although some stories were more persuasive than others. Manahatas Dance (2009), a compelling video work by Sung Hwan Kim, drew the audience into a seductive world of memory. The figurative sequences were quirky and melodic, while alluding to the political within eerie apparitions.

For Manifesta 8, A.C.A.F formulated a complex ‘Theory of Enigmatics’ which analyzed the condition of art today. Examining the function of the historical archive, the dissemination of fact and the subjective nature of truth, A.C.A.F aimed to re-address the existing knowledge and vocabulary that we rely on to reflect on human issues.

Displaying a ‘monument to impermanence,’ Jean Marc Superville Sovak’s It Can’t Last, No Rush (2010) offered a welcome tactile relief to the onslaught of dialogue. A precarious stack of crumbling red bricks each stamped with the word ‘Empire,’ attested to the notion that under the buildings of churches can be found the remains of mosques. This acted as a timely reminder that in the grand scheme of things, empires come and go.

Backbench (2010), a multi-channel documentary was the result of a three-day workshop with four collectives and two mediators. Participants debated issues such as sustainability within the biennial model. Unsure of the rules of engagement, the participants ultimately descended into a critique of the ‘critique model,’ providing a Big Brother lesson in democracy.

Simon Fujiwara aimed to question the subjective nature of truth in an installation called Phallusies (2010), This mock archaeologist’s office was devoted to the discovery, preservation and documentation of a giant stone penis. Here, Fujiwara questioned the validity of media, archive and eyewitness accounts, conceding that ‘the truth is a slippery thing.’

Simon Fujiwara: Phallusies

former Post Office, 2010, photo Ilya Rabinovich

Image held courtesy of Manifesta 8.

The Media’s relationship to the construction of reality was most actively pursued by C.P.S in ¿The Rest is History?. Examining the divisive strategies of media production, C.P.S proposed that “reality is not a fact to be understood, but rather an effect to be produced.”

Presenting a series of transmissions that examined the production of truth, C.P.S skillfully addressed issues of visuality, surveillance and conflict within the spectrum of mediation and reportage. Fay Nicholson’s weekly printed installments in a local newspaper, La Verdad (2010), aimed to highlight the role of the printed mass media in the circulation of local realities. What We Might Have Heard in the Future (2010) was a radio-theatre piece by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere. Futuristic conversations and automated voice verification posed a Roland Barthes-style question: “What would become of a society that ceased to reflect on itself?” Stefanos Tsivopoulos’ Amnesialand (2010) offered an illuminating perspective on documentary-fiction. On reflection, this series of installed projections alluded to spiritual matters and questioned where images of memory go when people die.

The publication Nolens Volens No.4 was edited in collaboration with C.P.S member Alfredo Cramerotti and informed by the collective’s curatorial role in Manifesta 8. The text comments on a shift in the production of truth – from news media to art – by re-functioning an investigative tradition back into the public domain. This process raises doubts about the claimed objectivity of traditional formats, and encourages the audience to question their own position.

Crucially, it seems, art does something that journalism fails to do; it reflects on its own methods and means of production. For Manifesta 8, this reflection ruminated over the apparatus of the biennial format– a worthwhile, if slightly self-conscious effort. An astute observation proclaimed by Colonel attests to the fact that sometimes it pays to “monkey with the Monkey Machine.”

Joanne Laws is an artist and critical writer based in the west of Ireland.

___________________________________________________________________________________